In his second of a series of Gemstone Conversations columns for Gems&Jewellery, jewellery historian and valuer John Benjamin FGA DGA FIRV considers how amethyst has been used by jewellery designers throughout history.

This transparent variety of crystalline quartz is surely one of the most distinctive and recognisable gemstones ever used in decorative jewellery. It has never really declined in popularity, no doubt because of its instantly recognizable colour, its availability and, going back to earliest times, its strong association with spiritual goodness, virtuous behaviour and, as far as the Ancient Greeks were concerned, its defence against intoxication.

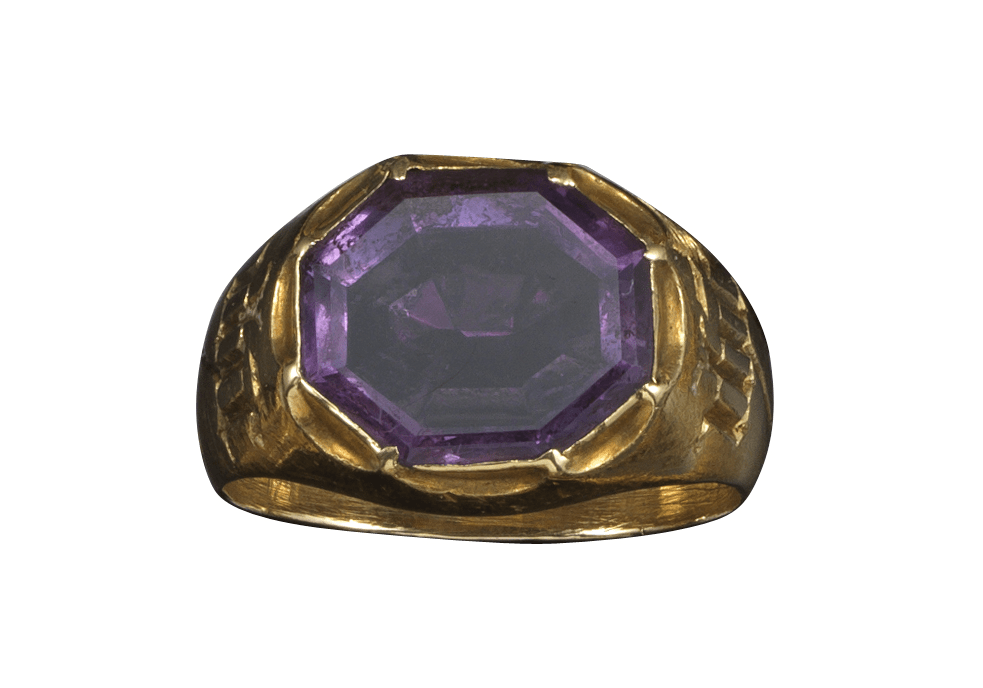

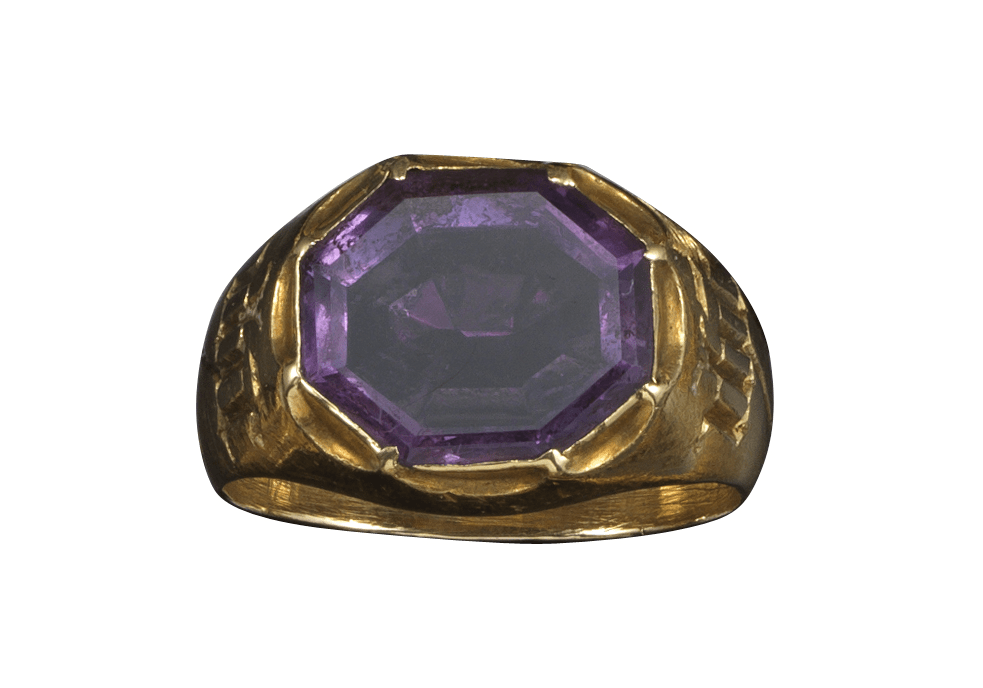

A 19th-century amethyst-mounted gold Bishop’s ring, with an octagonal-shaped amethyst set in yellow gold with the inscription ‘dic’ in latin to each shoulder, which translates to ‘to tell’ or ‘to say’. Image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

Amethyst – A Symbol of Status

Setting aside its many reputed magical and talismanic benefits, amethyst’s eye-catching colour had the added advantage of suggesting wealth and status, so it was perhaps inevitable that it frequently became the gemstone of choice for prosperous merchants and powerful dignitaries in Rome and Egypt. No doubt it helped that it provided the ideal medium for cutting into cameos or engraving as intaglios — lapidarists tended to favour pale lilac colour examples since they tended to exhibit greater detail than the deeper purple varieties.

A Neoclassical amethyst intaglio, the oval-shaped amethyst plaque engraved with a scene depicting sea nymph Nereid riding a hippocampus possibly on the way to the wedding of Poseidon and Amphitrite, with a pseudo signature for the ancient engraver Gnaois (active 40-20 BC) quartered with seed pearls beneath a hinged seed pearl pendant loop in yellow gold. Image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

Their use continued right through the Middle Ages where knobbly and irregular cabochons were often set into gold rings, ring brooches and as a decorative embellishment to the bosses of earrings and buckles. Its popularity spread throughout Europe and no doubt due to its associations with piety, humility and celibacy, amethyst was adopted by the Church, becoming the gem we most closely associate with massive gold rings worn by Popes and Bishops.

Amethysts as an Antidote

By the 16th century amethyst was considered to be the ideal antidote curing everything from drunkenness to nightmares and, indeed, Mary Queen of Scots wore an amethyst to dispel her natural (and not unreasonable) tendency towards melancholia. There are a number of pale amethysts forming part of the incomparable Cheapside Hoard. These plain, oblong-shaped tablets are quite pale in colour and were generally known by the term ‘Rose de France’. Early 17th century examples such as these have a wonderful ‘monumental’ quality especially when set as finger rings in plain gold mounts coated in solid white enamel.

A pair of Regency amethyst and gold cannetille drop earrings, the two-section earrings each centred with a pear-shaped amethyst and set with smaller amethysts. Image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

Amethysts in 18th Century Jewellery

Advances in diamond cutting and polishing by the middle part of the 18th century resulted in large and colourful semi-precious stones – especially amethyst, aquamarine and topaz – being mounted in clusters of ‘old-mine’ cut diamonds in the form of cushion and pear-shaped earrings, brooches, necklaces and diadems. Invariably set in silver, these gems would often be foiled at the back to reflect the light, a particular feature of the Georgian jewel at a time when much of it was being worn at formal events such as balls that were lit by twinkling candlelight in chandeliers and candelabrum.

Read more: Amethyst for Those Born in February

This was very much the era of experimentation in colour and amethyst was often set in bright yellow gold filigree frames known as ‘cannetille work’ with other compatible gemstones especially chrysolite, turquoise, half pearl and peridot.

A French amethyst and gold cased parure, comprising of a rivière necklace, a pair of bracelets, a brooch and comb. The necklace is set with 28 graduated oval-shaped amethysts, while the hair ornament is formed with a row of slightly graduated foliate open work scrolls, surmounted with fifteen oval shaped amethysts and with a gilt metal comb section. Circa 1815. Image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

Amethyst from Brazil

By the early 19th century the discovery of large amethyst deposits in Brazil inevitably led to an increase of the gem on the market, no doubt helped by the fact that members of the aristocracy favoured the rich opulence of its colour. In 1837, the Russian Emperor Alexander I presented Frances, Third Marchioness of Londonderry, with a splendid set of Siberian amethyst and diamond jewels. Without doubt, these Russian specimens are the most desirable colour of all — a deep ‘Imperial’ purple with a distinctive red secondary hue.

Amethyst in 20th Century Jewellery

Less valuable – but equally popular – amethyst continued to be used throughout the 19th century. By the Edwardian era, pale Indian specimens were the gemstone of choice for simple fringe necklaces, inexpensive brooches and pendants with seed pearl decoration.

The stone dwindled in demand through the 1920s and 1930s but saw a revival in post-war ‘Retro’ jewellery in which larger, emerald-cut and pear-shaped specimens were often set in angular or three-dimensional combinations with other bold coloured gems including turquoise and ruby. These are very much jewellery for the purist but certainly make a dramatic impact, a good example being the amethyst, turquoise and diamond Bib Collar made by Cartier for the Duchess of Windsor in 1947.

A pair of amethyst and turquoise double clips, c.1950, set with graduated emerald-cut and circular-cut amethysts and turquoise cabochons in yellow gold. Image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

Availability and affordability are key attributes where gemstones are concerned and through the 1960s and 1970s designer-jewellers in London such as Andrew Grima and John Donald produced striking and highly original creations using amethyst in abstract and unusual gold settings, recognising that amethyst would always be a gemstone to catch the eye and make an impression. It is the sheer beauty and versatility of this beautiful gem which has meant that it has never lost its appeal over literally thousands of years.

John C Benjamin FGA DGA FIRV is an independent valuer, jewellery historian and author of Starting To Collect Antique Jewellery. Find out more at johnbenjamin.co.uk

This article was originally published in Gems&Jewellery Summer 2019, Volume 28, No.2. Look out for John’s next Gemstone Conversation in the next issue of Gems&Jewellery.

Do you aspire to work in the gemstone and jewellery industry? Our Gemmology Foundation course is the perfect first step towards building your gemmological knowledge. Are you passionate about diamonds? Take a look at our Diamond Diploma course.

Cover image: An Edwardian gold amethyst and seed pearl set necklace with pendant, the gold necklace mounted with five graduated oval-shaped amethysts with seed pearl set fringe. Suspending a detachable amethyst and graduated seed pearl brooch/pendant (one section missing). Image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.