Curator Alan Bronstein reveals how the world-renowned Aurora Pyramid of Hope evolved and shares the story behind his lifelong passion for coloured diamonds.

It is difficult to trace all the challenges, twists and turns, triumphs and failures, which characterise the journey of a dream from fantasy to reality. For me, it all began with one experience, one stone, and one revelation. In 1977, as a college graduate who could not find a job, it was suggested by my mother Jeanette, the book-keeper at the New York Diamond Dealers Club, that I become a diamond broker.

Such a job only required you try to sell loose colourless diamonds from one dealer to another. Such a job did not require any skills other than banging on doors (you could still do that in 1977) and getting offers on the diamonds you were soliciting. I found it to be one of the least fulfilling ways I could spend my time, as diamonds were already becoming commoditised by the price lists all diamond dealers carried. As a result, the illusion of what might be a visually beautiful stone disintegrated when it was deemed not to fit within the defined parameters of the emerging grading system, which qualified the stone on paper as a commodity.

As fate often intervenes at the moment it is most necessary, just as I was about to make my break for the unknown, I saw something I had never seen in my years as a diamond broker; a yellow diamond that shined like the sun, hypnotising me and opening my mind to something new and exciting. Although it was part of the natural diamond world, it was a well-kept secret. Not because they had no beauty but because diamond dealers did not know how to make money with them, and thought they were the poor cousins to the 98% highly-promoted and coveted colourless diamonds. There were no discussions about them, they were never advertised and remained an underground trade that was only mentioned among the few aficionados in the diamond industry who collected them as curiosities, simply because they could not sell them.

Into this small group of connoisseurs, I was embraced as a broker and as a peer because of my intuition for recognising the idiosyncrasies within the colours of the diamonds. This small group of mentors allowed me into their private world, and I learned what to keep my eyes open for from their experience and knowledge. This is the ultimate and true way to learn, from the wisdom of experts that have come before you. What a gift to be allowed to study among this exclusive club of dealmakers.

Starting with Yellow Diamonds

The first thing I learned was not all yellow diamonds have the same colour characteristics. I saw all different colour reflections in almost every stone I looked at carefully. At this time, in 1980, the grading system so highly-regarded in colourless diamonds was generalised in coloured diamonds, to say the least. All yellowish diamonds were called yellow. All pinkish diamonds called pink. Yet when you had an opportunity to make comparisons, you could often see major differences in saturation and colour modifiers that were not identified by the labs.

Instinctively, one could tell that the science of natural colour diamonds was in its infancy and that to determine a greater hierarchy of colours, perceived as more desirable, would be an advantage to finding, selecting, buying and selling the prettiest stones. It was the fork in the road I was travelling.

I set out to find small sample stones that would be my standard for analysing differences that were hard to notice without comparison. These few small sample stones became the foundation for my business and for the concept that would become the Aurora Pyramid of Hope.

Soon my interest and passion turned into an obsession. Every day I would enthusiastically go hunting for unusual diamonds as the colour matrix began to fill in. Often I would see something new, something different, quite often with dealers who did not know what to do with their curiosity.

Soon I realised even though many stones had similar colour characteristics and intrinsic colours, when scrutinised subtle differences would become clearer leaning toward a spectral modifier. Even the shape and cut, angles and facet arrangements of the stone would change the appearance of the face up colour.

Sourcing Coloured Diamonds

This was a turning point, as I decided without the means to do so, that I would try to organise a collection with as many different colours as I could find, afford and obtain. The colour of the stones, many of which one would find extraordinary and many that were commonly seen, would be the primary driving force for gathering. Other factors like size, natural inclusions, and natural phenomena like fluorescence were secondary to trying to find stones that fit the universal matrix of colour in nature and specifically diamonds.

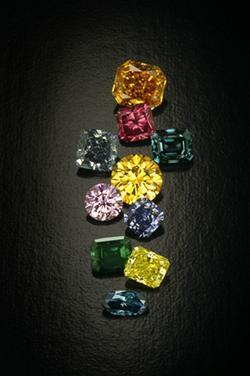

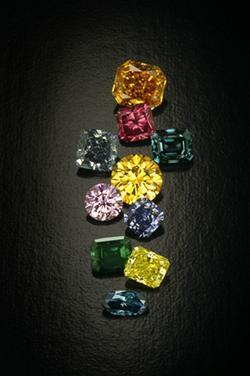

For the last 37 years, beginning with the first sample stone to the present, I have collected 296 diamonds that now compose the Aurora Pyramid of Hope. The collection has gone through a metamorphosis in its composition and its meaning. It has served a great purpose for science, through studies of its colours at museums and laboratories around the world, and revealed many secrets that have advanced our understanding of these rare gemstones.

Waterfall: Polished diamonds from the Aurora Pyramid of Hope collection. Copyright The Trustees of NHM, London. Image courtesy of Robert Weldon.

As the colour matrix began to fill in, it took on a new meaning for me. At some moment my consciousness gave way to the concept that the pyramid was not just a science project but also a work of art in a new medium. A painting using only unmounted loose diamonds had never been seen before.

Introducing the Aurora Pyramid of Hope

I saw humanity in the collection as it grew. All the colours, shapes and inclusions were the perfect metaphor for all the races, colours, religions, faces of people and the infinite personalities that make us all individuals. I am also of the belief that we are related to diamonds, because we are made from the same essence created by the universe – carbon – the key element in all living things. Although natural diamonds seem inanimate, they reveal life through their brilliance.

The pyramid shape itself has many spiritual and historical meanings that add to the symbolism I have tried to create. As does the name Aurora, the Roman goddess of the sunrise, and the colourful lights that appear at the northern and southern tips of the earth.

When the collection was about to go on display at The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, all the stones were in parcel paper and it was at this moment that I had to figure out how to present them. As I experimented with different forms, by laying out stones, it soon evolved naturally into the pyramid shape seen today. It unconsciously pulled me in that direction and I was pleased at its display and play of colours.

I have many favourite stones in the collection; some for their stories and some for their extraordinary colours. One such amazing story is when a South American miner showed me a small rough diamond that was opaque and coated black. He had cut one flat surface into the stone so when you peered through this window it appeared green in colour. Many stones like this were colourless inside when you removed the skin coating the stone, which was caused by natural radiation in the ground. Other stones with this outer skin were often black or ground into diamond powder, because they were not considered gem material.

This particular stone was re-examined in the lab during the multiple phases of cutting over one year, to make sure it was the same specimen and that it had not been treated from the previous observation. At the end of the process, to my shock and that of the lab, it emerged as the most beautiful natural green diamond I have seen to this day.

The collection is, however, dynamic, and I have continued to collect and look for missing pieces to the puzzle. A further 36 stones were added in 2005 when the collection went on exhibit at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London, joining the original 260 documented in 1998. I also replaced 20 stones that I felt would improve the variety and aesthetics of the original suite, thus the pyramid is greatly improved from its original museum exposure in 1989 at AMNH in New York where it spent 16 years.

The Pyramid of Hope’s sister is the Aurora Butterfly of Peace; a collection evolved from the desire to make a pure artwork painting with natural colour diamonds. It was a 12 year process of building and arranging its mythic shape. Although the concept behind the pyramid began as science and became art, the butterfly began as an artwork and was also a bounty for science. It is proof that nature is science and art, and nature is the greatest artist of all.

Along with its sister, the Aurora Pyramid of Hope is meant to be a universal non-secular artwork and symbol to point humanity to our common purpose for living; hope, peace and love. It serves as a legacy for all mankind. Alan Bronstein is the curator of the Aurora Pyramid of Hope with the financial assistance of his late step-father and business partner Harry Rodman. ■

Gem-A members can log in to read the full article Gems&Jewellery Spring 2017 / Volume 26 / No. 1

Interested in finding out more about gemmology? Sign-up to one of Gem-A’s courses or workshops.

If you would like to subscribe to Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology please visit Membership.

Cover image From the Aurora Pyramid of Hope collection – rough and polished diamonds. Image courtesy of The Trustees of the NHM, London.