From the Summer 2018 issue of Gems&Jewellery, Gagan Choudhary FGA, deputy director of Gem Testing Laboratory Jaipur, describes the various types of fake gem rough that has passed his desk in recent months, including mica rock presented as emerald rough, cubic zircona and topaz fashioned as diamond octahedtrons, and synthetic quartz mimicking aquamarine.

Reaching directly to the miners for procuring rough has always been profitable, but involves a huge amount of risk unless one has enough experience in buying at the source, deep knowledge about the stone being purchased, and handling the pressure thereof.

Often, there have been cases when dealers tend to forget the possibilities of scams and frauds at mining sites or the markets nearby. The sellers at such locations often present glass, synthetics, treated gems or other cheap natural materials as expensive gems in order to make some quick money. This practice has been prevalent at most of the major mining regions around the world for decades.

At Gem Testing Laboratory Jaipur, we routinely encounter such cases, some of which are presented here:

GLASS-FILLED MICA-ROCK, PRESENTED AS EMERALD ROUGH

Recently, a 1,075 gm black micaceous rock was presented for identification (1), a true example of a fraudulent rough, which, although not shocking to us, was definitely an interesting one. Initial observations with unaided eyes from different angles suggested the presence of several crystals, with hexagonal profile, embedded in the rock.

Such rock formation is a common sight for those dealing in emerald rough, especially from locations where emerald is associated with mica (phlogopite) schist, such as Zambia. Careful observation using strong fibre-optic light surprised us. Under reflected light, only small areas or corners of the embedded crystals appeared green.

The rest appeared dark, due to the presence of black mica on and around crystals.

1: This 1075 gm micaceous rock was embedded with elongated ‘hexagonal’ crystals of artificial glass (marked with arrows).

Note the difference of texture around embedded crystals and rest of the rock.

However, when light was transmitted through these crystals, they appeared bright green, which raised suspicion about their origin. Such bright green colour under transmitted light, especially in an embedded crystal, had never been seen before. Further examination revealed a granular texture around these embedded crystals, while the rest of the rock appeared flaky; this supported our suspicion.

These features suggested that micaceous rock was first drilled, filled with green ‘hexagonal’ crystals artificially, and then the joints were covered with a mixture of glue and black mica.

When observed under ultraviolet light, corners of the embedded crystals (micafree areas) fluoresced chalky-yellow green. Raman analysis confirmed these embedded crystals as artificial glass.

MICA-COATED GLASS IMITATING EMERALD ROUGH

Another form of emerald-rough imitation are these mica-coated glass (2). In this case, pieces of green glass are first fashioned in the shape of hexagonal rough, which is then coated with fine powder of black mica mixed in glue, followed by a layer of mica chips. These worked-up pieces are then taken to the mining sites by the middlemen and mixed in parcels of low-quality natural emeralds.

The illustrated glass specimens here were seen in a parcel of emeralds from Jharkhand, India.

2. Glass samples worked-up to imitate emerald rough by fashioning into hexagonal crystals and coating with black mica.

Found mixed in a parcel of natural emerald.

SYNTHETIC RUBY FROM MOZAMBIQUE

We came across a small parcel of rough rubies (five pieces, weight range of 3.60- 18.06 ct) submitted for identification. All the specimens were tumbled with a corroded surface and interestingly coated with a yellow-brown substance. Most of the samples were free from inclusions, but under immersion microscopy all displayed curved growth lines, characteristic of synthetic ruby grown by Verneuil process (3).

Appearance of these specimens clearly suggested that they were presented as natural. Prior to this we have seen many more specimens of synthetic ruby, and in much larger sizes, presented as natural. As per the discussion and information from the depositor, these stones were purchased in Mozambique.

3. Rough Samples weighing 3.60-18.06 ct were identified as synthetic ruby.

note the presence of yellow-brown substance on the extreme right, imitating mud on natural rough

NATURAL AND SYNTHETIC RUBY COMPOSITE

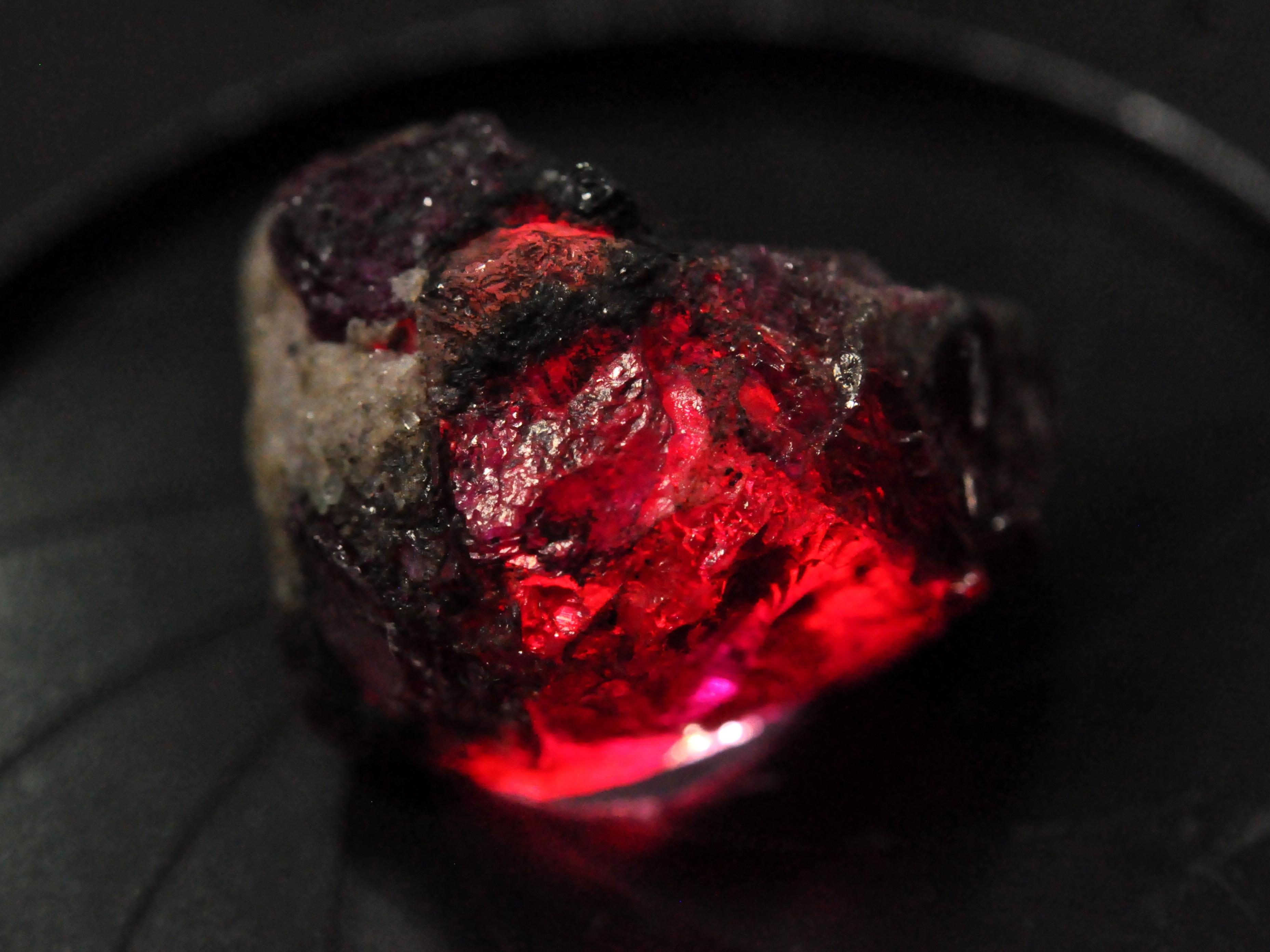

This 28.73 ct bright red rough, associated with some black and white minerals, was presented as a natural ruby. Upon initial examination with unaided eyes, the surface displayed some areas of milky angular zones against a pinkish to purplish background, typically seen in natural ruby crystals.

When examined under transmitted light, a large central area of the specimen appeared bright red, while the edges appeared dark and opaque (4). This raised suspicion about the origin of this rough.

Careful examination under the microscope revealed a sudden change. of growth and inclusion patterns, not only in the core and surface, but also within the surface; the surface displayed small chips with different inclusion patterns.

In addition, distinct colour variation between the core and edges of the specimen was evident. These features suggested that the specimen is a composite where a transparent piece of synthetic ruby is covered with small chips of natural ruby.

4.This bright purplish red-pink rough(top) is a composite of synthetic and natural ruby. The central part is a synthetic ruby while the out part is composed of chips of natural ruby.

Under transmitted light (bottom) the central synthetic part of the specimen appeared bright red, while the edges appeared dark and opaque.

SYNTHETIC SAPPHIRE, PRESENTED AS NATURAL ROUGH

Synthetic counterpart is a common imitation for natural sapphire rough; these are presented in two forms — one as broken, tumbled rough, and second, as fashioned, well-formed hexagonal-pyramidal crystals with surface markings (cover image). Although, their identification is not challenging in a gem lab, they might pose problems while buying at the mines.

The specimen illustrated in (5) was found mixed in a parcel of sapphires, purchased in Madagascar.

5. These two crystals, weighing 63.93 (left) and 44.66 (right) ct displaying bipyramidal habits and associated white mineral, were submitted as sapphire.

The crystal on left was identified as sapphire, but one on the right as glass.

GLASS AS SAPPHIRE ROUGH

Two blue crystals weighing 63.93 and 44.66 ct, as illustrated in were submitted together. Both crystals displayed bi-pyramidal habits and associated white mineral, typically seen in corundum. Interestingly, there was an obvious difference in colour and transparency of both the crystals; the crystal on the right had much better colour and transparency.

Closer inspection of the bright blue crystal revealed hemispherical cavities on its surface, coloured swirls and numerous gas bubbles — the features associated with glass. The grey-blue crystal (5, left) was proved to be natural sapphire, while crystal habit and associated white mineral (kaolinite) suggested Kashmir as its origin.

CUBIC ZIRCONIA AND TOPAZ AS DIAMOND OCTAHEDRON

Cubic zirconia as diamond imitation, both rough as well as cut, have been in existence for a long time, however, in recent years colourless topaz has become a frequent encounter in diamond imitation, especially in rough form. Image 6 illustrates one such example, where the left specimen is a cubic zirconia while the right one is topaz.

6. Cubic Zirconia (left) topaz (right).

These stones are fashioned as typical crystal forms associated with diamond, here, octahedron; often striations, grooves or triangular markings are created on these fashioned octahedrons, giving them a natural appearing crystal.

In the recent past, this author has encountered some large packets of such created ‘topaz octahedrons’, being presented as diamond.

Separation of cubic zirconia from diamond was easily done on the basis of higher specific gravity, while topaz by its anisotropic optic character. Although identification of these imitations is straightforward, when buying at mines or open markets one has to be careful.

TREATED QUARTZ AS EMERALD ROUGH

In addition to the glass discussed above, emerald rough is often imitated by coated (7) or dyed quartz.

There have been cases where transparent quartz is painted with green colour and presented as emerald, however, as illustrated in 7 (left), such materials can be separated by crystal form (prism and rhombohedral faces) and horizontal direction of grooves or striations on prism faces.

Another material is the quartzite variety, which is first dyed green, then fashioned as hexagonal crystal shape to imitate emerald; such fashioned crystals are often coated with black mica too.

Even body colour, translucency and absorption spectrum (band at 650 nm) can separate such dyed materials from natural emerald.

7. Quartz crystals painted with green colour and coated with black mica are presented as emerald rough.

Also note the horizontal direction of grooves or striations on prism face.

SYNTHETIC QUARTZ AS AQUAMARINE CRYSTAL

This is one of the most unusual materials this author has seen for making a fake crystal — synthetic blue quartz fashioned as an hexagonal crystal of aquamarine (8). The crystal was fashioned into six-sided prisms, with pyramids and basal pinacoids — a crystal form commonly seen in aquamarine.

The crystal also contained a conical-tube with brown epigenetic material (such as iron oxide filling) visible to the unaided eyes. On observing the crystal from different sides, it displayed two parallel planes (seed plate) with colourless area and an attached metal clamp. Such features are often seen in synthetic quartz and other gems grown by hydrothermal process.

When viewed from the top i.e. down the ‘c’ axis, the interfacial angles between the prism faces ruled out the possibility of natural crystal form associated with crystals belonging to hexagonal crystal system, such as beryl.

As per the precision at which the nature operates, opposite sides of prism faces are parallel to each other, while in this case no opposite sides were parallel. Identification of this specimen as synthetic quartz was established on the basis of ‘bull’s eye’ optic figure, seed plate and infra-red spectra.

Such cases remind us of the importance of studying crystallography, not only for the identification of gem rough, but also in the creation of fake rough, which the maker of this fake missed out on.

8. Left: blue specimen presented as aquamarine was a synthetic quartz fashioned into a hexagonal crystal, terminated by pyramidal and pinacoidal faces. Also note the conical tube containing brown epigenetic substance.

Right: the top view of the synthetic quartz specimen

CONCLUSIONS

Fake rough is an inevitable part of the gem trade, and the scams associated with this are increasing day-by-day. Identification of rough, especially in the field is quite challenging, however, one needs to keep in mind the existence of fake material in local markets or even mines.

Careful inspection of the presented rough before making a buying decision is always advisable, keeping in mind the crystallographic features. ■

All images courtesy of the author.

This article originally appeared in Gems&Jewellery Summer 2018/ Volume 27/ No.2

Interested in finding out more about gemmology? Sign-up to one of Gem-A’s courses or workshops.

If you would like to subscribe to Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology please visit Membership.

Cover Image: Synthetics presented as natural rough tumbled sapphire. Image Credit: Gagan Choudhary.

{module Blog Articles Widget}