Having successfully completed her Gemmology Diploma and Diamond Diploma, Charlotte Pittel FGA DGA shares an abridged version of her excellent project on Cardinal Jules Mazarin and his legendary love of diamonds.

The Mazarin diamonds were a collection of 18 diamonds left to Louis XIV and the French Crown Jewels by Cardinal Jules Mazarin. Discovering the story of this group of diamonds, the man who collected them and what happened to them is like an incredible work of fiction.

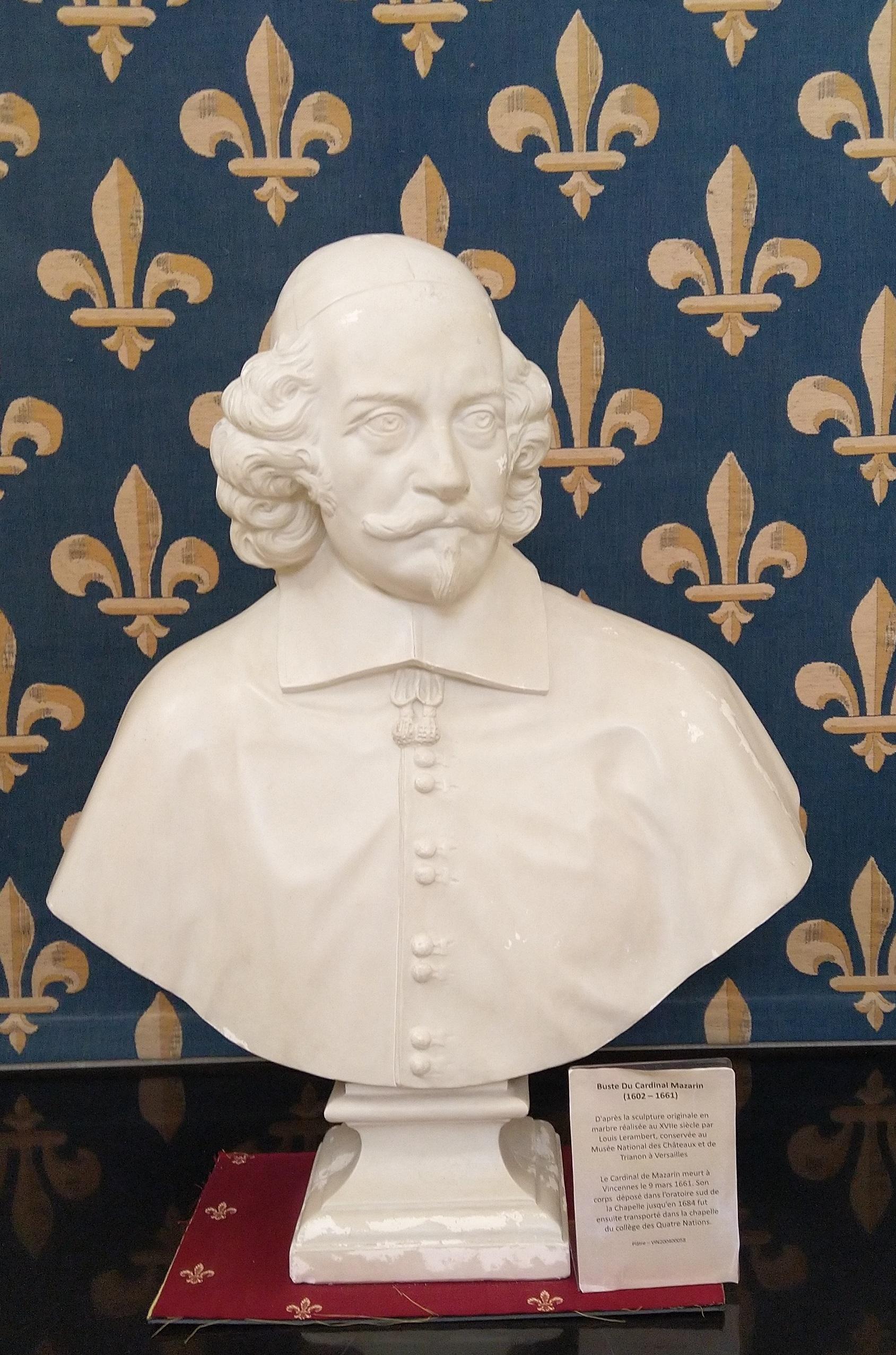

The Life of Cardinal Mazarin

Born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino on July 14, 1602 to a minor Italian noble family, Mazarin was a man of many interests and talents. His early education was at Jesuit school in Rome before studying law in Madrid. On his return to Rome around 1622 he attended the University of Rome La Sapienza, and following a spiritual awakening he entered the pontifical army.

In 1628 he joined the diplomatic services for the Holy See and became involved in Italian politics whilst working alongside the Cardinals Sachetti and Barberini. His subtlety, patience and hard work were recognised and in 1630, during the war between France and Spain over Mantua, he was sent to negotiate with Cardinal Richelieu.

Richelieu, impressed with the young man, invited him to Paris where he soon became a confidant and advisor to the Cardinal, joining the court of Louis XIII and Queen Anne d’Autriche. After taking French citizenship he became known as Jules Mazarin and in 1641, was promoted to the rank of Cardinal.

Following Richelieu’s death in 1642, Mazarin succeeded him as the Chief Minister of France and, after the death of Louis XIII in 1643, assisted the Regent Queen Anne in governing France on behalf of her then child son, Louis XIV.

Mazarin was a keen student of the arts, but diamonds were his first love. His collection contained the most beautiful examples, many of them sourced from other European royal families, his preferred jewellers of the time including Lescot, Gabouri, Lopés, and almost certainly from renowned traveller Jean Baptiste Tavernier (1605-1689), who would also supply King Louis XIV.

Following his death, Mazarin made generous donations to hospitals, hostels and the arts, and bequeathed his extensive collections of jewellery and gems. Queen Anne received the Rose d’Angleterre (a large round diamond of approximately 14 carats) and a perfect cabochon ruby in a ring.

The Duc d’Orléans received 31 emeralds, while Queen Marie-Thérese was bequeathed a cluster of diamonds. Among his more noteworthy instructions, however, was his wish that a collection of 18 diamonds be given to the King and the Crown of France, on condition that they carry the name Mazarin.

The Famous Mazarin Diamonds

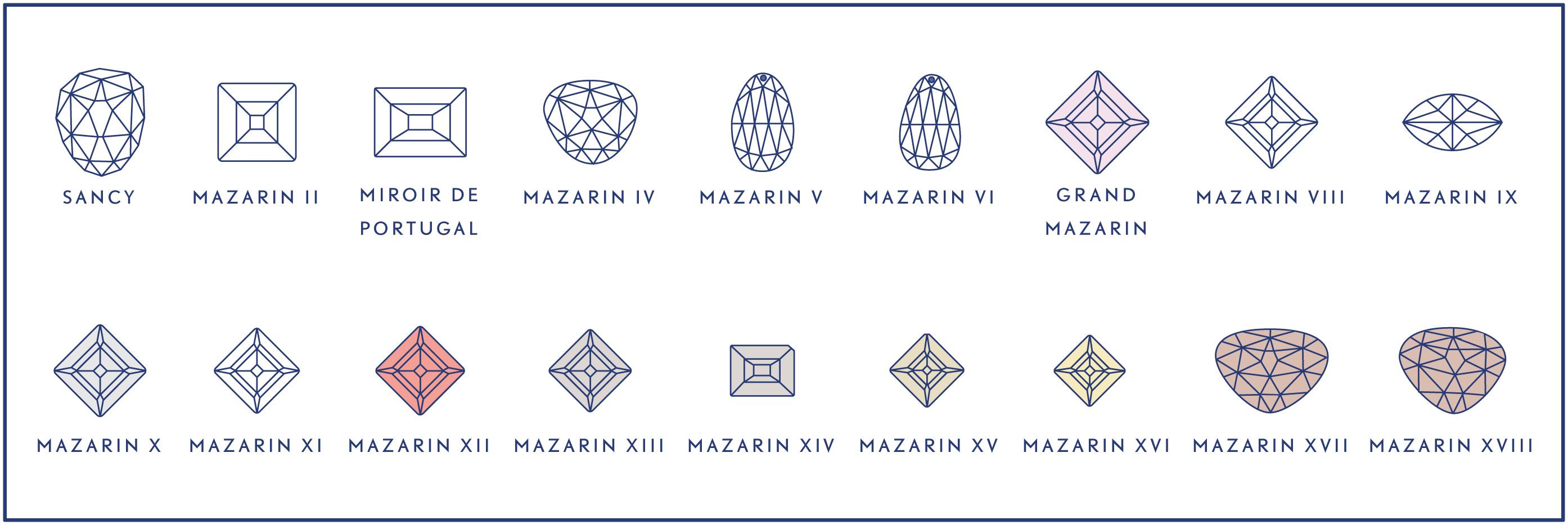

Mazarin assembled this rare and beautiful collection of 18 stones towards the end of his life. Only three of these stones are named: the Sancy, the Mirror of Portugal and the Grand Mazarin. Sadly, due to the tumultuous nature of 18th century French history, many of the 18 stones have disappeared.

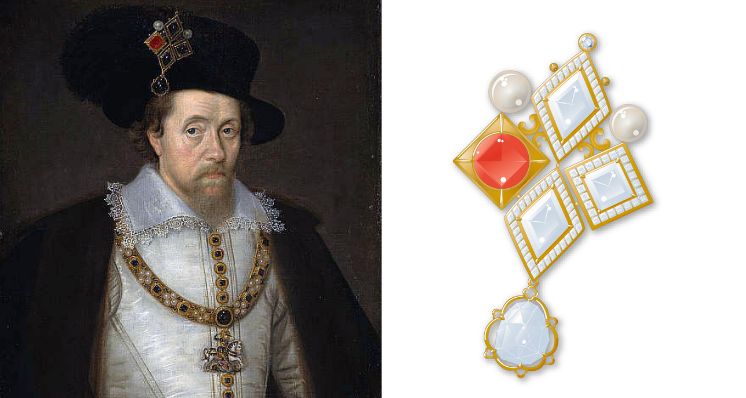

An impression of the Mirror of Great Britain, as seen affixed to King James I’s hat in a portrait that is housed in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Image: Charlotte Pittel.

The Mazarin I — the Sancy Diamond

It is believed that the 106 (old) carat Sancy formed part of the collection of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Following his death it disappeared for over 20 years, finally reappearing in Germany in the hands of a merchant banker named Jacob Fugger. He planned to sell the diamond to the King of Portugal, Don Manuel I, and re-cut it into the pear shape we see today.

During a period of huge political upheaval and conflict between England, France, Spain and Portugal, the diamond would finally end up in the collection (and take the name) of Nicholas de Harley, Seigneur de Sancy and Baron de Maule (1546-1629).

De Sancy was made Superintendent of France by Henry IV and pledged his diamonds to raise money for the crown. In 1596, however, he negotiated the sale of the stone to James I of England, who set the Sancy as a pendant into the jewel known as the Mirror of Great Britain.

Read more: Diamond for Those Born in April

James’s successor Charles I sold off precious stones to raise funds for the Royalist cause and, in 1644, sent his consort Queen Henrietta Maria to France to secure supplies and munitions. She borrowed enormous sums from the Duke of Epernon and pledged the Sancy as collateral. In 1649, when Charles I was beheaded, the Queen was exiled. The Sancy diamond was claimed by the Duke and subsequently sold to Cardinal Mazarin.

The Sancy then became part of the French Crown jewels and was mounted in Louis XV’s coronation crown in 1722. Today, the Sancy is on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

John de Critz’s 1604 portrait of James I shows the King wearing the legendary ‘Mirror of Great Britain’ jewel. Image: Public Domain.

The Mazarin II Diamond

Author Bernard Morel suggests that this stone could well be the Pinder diamond, based on a 17th century description and drawings made by Thomas Cletscher. Sir Paul Pinder was a businessman and diplomat and, in 1611, James I made him an ambassador to Turkey where he managed to acquire some exceptional jewels, including the Pindar.

Called at this time the Great Diamond, it was acquired by Charles I in 1625 for 18,000 livres but not paid for. It is likely that this is one of the stones pledged by Queen Henrietta Maria in 1646 and then acquired by Mazarin, becoming known as the Second Mazarin.

It was included in a diamond chain worn by Louis XIV, before being re-cut and set into the centre of the Order of the Golden Fleece made by Jacquemin for Louis XV. Thereafter it was unset and remained in the collection of Louis XVIII until his death in 1824, at which time it was returned to the Crown collection. Sadly, the stone was stolen during the 1848 revolution.

The Mazarin III — the Mirror of Portugal Diamond

This stone belonged to Dom Antonio, Prior of Crato. After a short period with Elizabeth I and named the Portugal Diamond, it was mounted into a pendant set with a large pearl drop and given to Henrietta Maria on her betrothal to Charles I. It eventually became a part of the Mazarin Collection.

Read more: Questions to Ask When Buying a Piece of Gemstone Jewellery

As was the custom, many of the French crown jewels were in settings that allowed a freedom in how they could be worn. As such, the Mirror of Portugal was set not only in Louis XIV’s diamond chain, but also in a hairpin worn by Queen Marie-Thérèse, which also bore the Grand Mazarin and some substantial pearls.

The Third Mazarin was unfortunately lost to the French Crown jewels when a substantial number of the jewels were sent to Constantinople never to return, including the Mirror of Portugal and many other Mazarins.

The Mazarin IV Diamond

This stone was first referenced in Bernard Morel’s book as being set into a pair of Girandole earrings created for Queen Marie-Thérèse. It is shown sitting as the top button with the Mazarin V as a drop. Its pair uses other diamonds, including the Mazarin VI as the drop.

An illustration of Queen Marie-Thérèse’s girandole earrings, inspired by the work of Bernard Morel, containing some of the Mazarin diamonds. These earrings were documented in the 1691 inventory of the French Crown Jewels and were valued at 500,000 livres. Image: Charlotte Pittel.

The Mazarin V and VI Diamonds

Both the Mazarin V and Mazarin VI were pierced at the top, so were perfectly shaped to be worn as drop earrings. Records suggest that both of these stones were cut by Francisco Ghiot of Antwerp: 1632 for Mazarin VI and Mazarin V in 1636. In a later inventory of 1774, they show up possibly as rings.

The Mazarin VII — Le Grand Mazarin Diamond

This legendary coloured diamond was sold at Christies on the November 14, 2017, achieving a price of CHF 14,375,000 (approximately GBP £10,969,567.60). A GIA certificate (No. 5182785154) and classification letter confirms that this historic light pink, old-mine brilliant-cut diamond is a Type IIa and weighs approximately 19.07ct.

Read more: The Geology of Diamonds

This diamond can be traced back to Indian mines near the Golconda trading centre, but quite how it came to Cardinal Mazarin is unknown. Once the diamonds were passed to Louis XIV and the Crown Jewels collection, it is believed that Queen Marie-Thérèse was the first to wear it.

Following her death in 1683, Louis regained the Grand Mazarin and added it to his legendary chain of diamonds. It was listed in the 1691 inventory as sitting at number five on a chain of 45 diamonds, numbered in descending order of size. It was added to the crown of Louis XV, along with the Sancy.

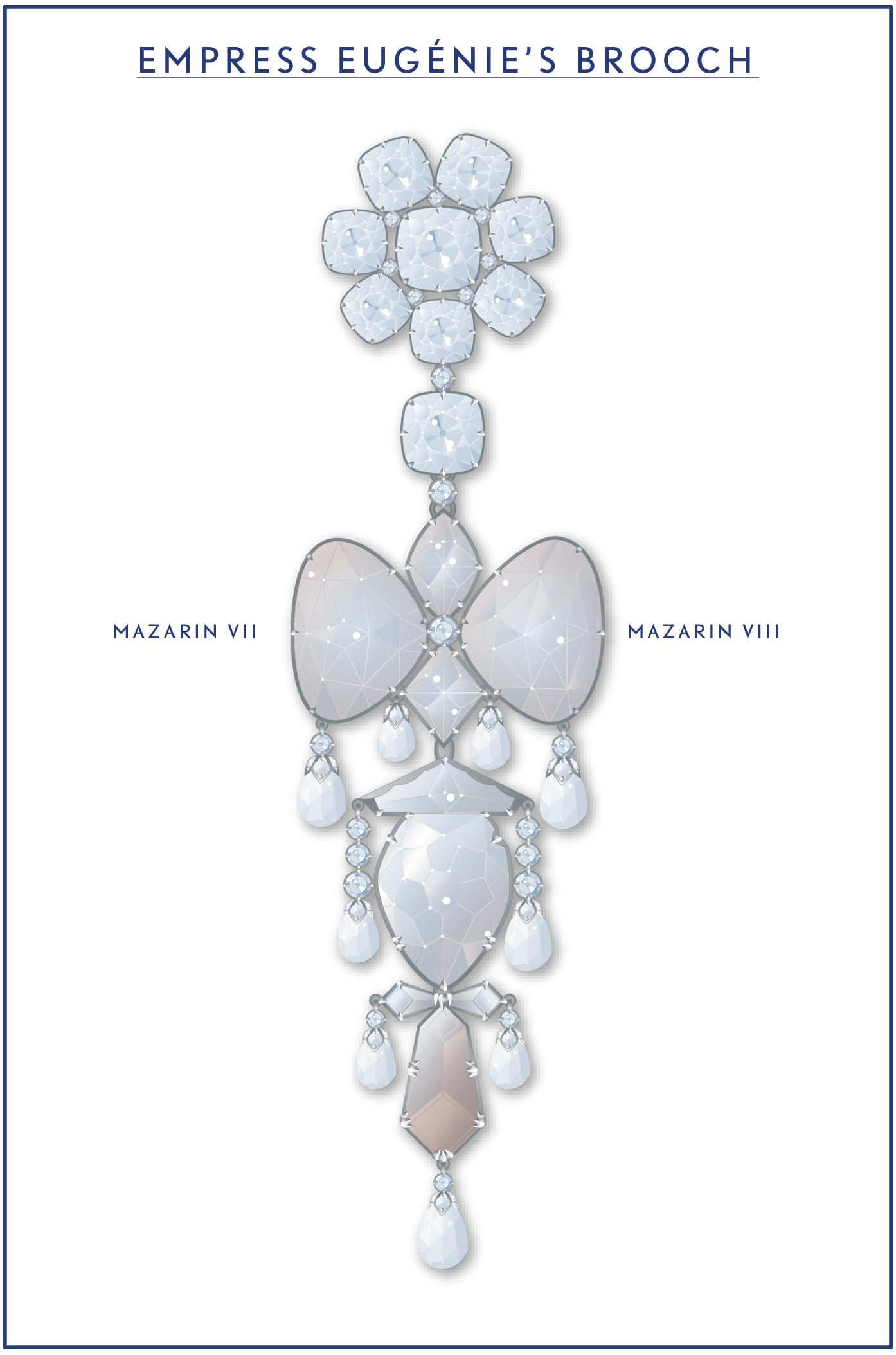

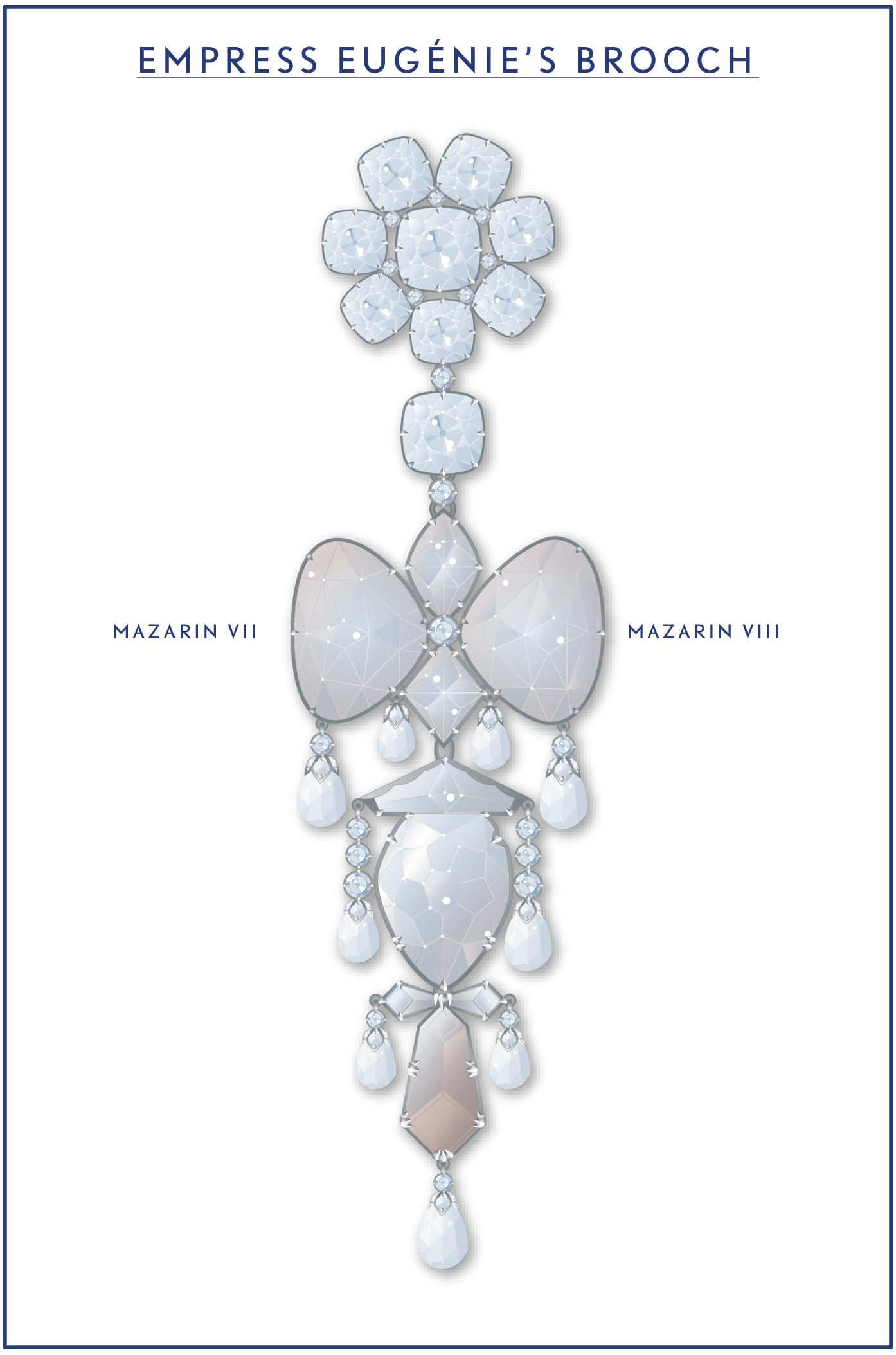

The Mazarin VIII Diamond

One of the few diamonds to survive a significant sale in 1795, this Mazarin stone sat at either position six or seven on Louis XIV’s diamond chain. The standout piece in which it featured, along with the Grand Mazarin, was the Diamond Diadem of Marie-Louise, Empress of the French from 1810 to 1814. A large diamond parure was ordered soon after the wedding of the Emperor and Empress, along with a coronet, a necklace, pair of bracelets, girandole earrings and a belt. There was also an order for a substantial diadem.

An impression of Empress Eugénie’s reliquary brooch designed and created by Alfred and Frederic Bapst in 1855. It was sold to the Louvre Museum in Paris in 1887. Image: Charlotte Pittel.

The Mazarin IX Diamond

Originally described as boat-shaped, the term ‘marquise’ was coined during the reign of Louis XV, largely due to a rumour that it matched the lip shape of his mistress, Madame Marquise de Pompadour. This diamond was set as the eighth button on one of Louis XIV’s justacorps (an open-fitted coat).

The Mazarin X — XVI Diamonds

Along with others, these diamonds were also included in the diamond chain belonging to Louis XIV and also in the coronation crown of Louis XV. The Mazarin XII was described as having a red colouration, probably due to the reddish flaw in its girdle.

The Mazarin XVII-XVIII Diamonds

The last two stones of the collection – XVII and XVIII – were virtually identical, with XVIII slightly larger. It seems that these stones were kept as a pair and used as buttons on a coat belonging to Louis XIV. They are most famed for being part of Empress Eugénie’s reliquary brooch of 1855, now part of the collection at the Louvre.

The Mazarin Cut

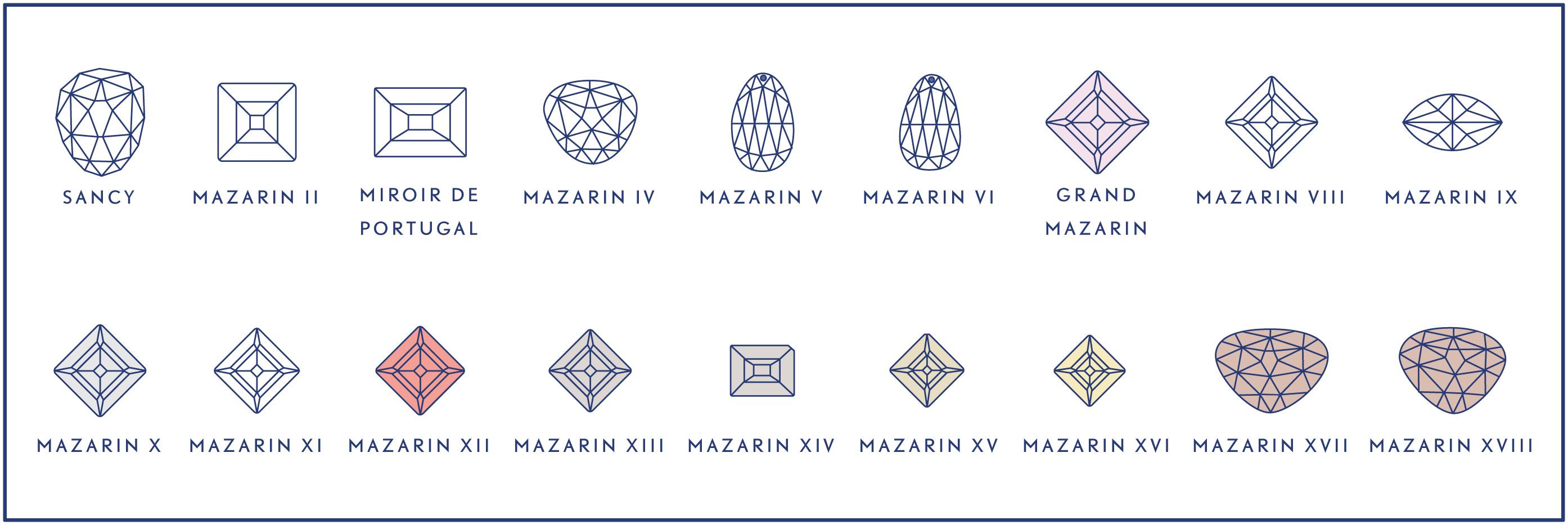

It should be noted that none of the 18 diamonds that Cardinal Mazarin bequeathed to Louis XIV were cut in the ‘Mazarin cut’. Instead, the cuts were as follows:

- Pear-shape double rose cuts — I (Sancy), V and VI

- Rectangular table cuts — II (Mirror of Portugal), III, IV

- Square table cuts — VII (Grand Mazarin), VIII, X, XI, XII, XIII, XV, XVI

- Heart-shape flat rose cuts — XVII, XVIII

- Marquise — IX

The fashioning of diamonds in 17th century Europe was undeveloped. Until the 1400s the natural form of the diamond was used, so an octahedral crystal or other rough was refined and set (known as the ‘point cut’). The table cut was first seen around 1477, marking the first true cut where the octahedron crystal had its top flattened by grinding and sometimes a culet added to the lower point. Varieties of the table cut are the thick table cut, the mirror cut, the tablet and the lasque cut.

A representation of the Mazarin Cut, inspired by the drawings and insights of Eric Bruton and Herbert Tillander. Image: Charlotte Pittel.

After the table cut followed rose-cut stones; a flat backed stone with a domed front. There were a variety of rose-cut styles in use at the beginning of the 15th century and it was considered the most appropriate cut for a flatter, thinner stone. Early brilliant cuts were first seen in the mid- 1600s, leading us back to the diamond-loving Cardinal Mazarin.

Single-cut or eight-cut diamonds had eight facets on the table and eight facets on the pavilion plus a culet. These then evolved into the double, cut with 16 facets on the table and 16 facets on the pavilion plus a culet.

It was in the mid-17th century that the Mazarin cut appeared, cushion-shaped with 34 facets in total: 17 facets on the table and 17 facets on the pavilion, including the culet, plus a girdle. This design of facets greatly increased the diamond’s reflective properties and it showed more fire and brilliance.

Although Mazarin was a devoted diamond collector, it is unlikely that he actually invented the Mazarin cut. However, he was a definite forerunner in the rise of popularity for this style of cutting and it is most likely that the cut was named after him as a tribute.

The complete version of this project, including references, appendices and a bibliography are available upon request. All images and illustrations are supplied by the author unless otherwise stated.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 issue of Gems&Jewellery.

Do you share Mazarin’s passion for diamonds? Enhance your knowledge with our Diamond Diploma.