The fascinating internal world of gemstones is an important area of study for gemmologists. Although some inclusions are common, others are far rarer and more elusive. Some professionals may go their entire lives without seeing these specific internal features in person. Here, Gem-A Tutor Pat Daly shares some ‘once in a lifetime’ inclusions and what they can tell us about their hosts.

It is uncommon for gemstones to be free from inclusions. The great majority enclose crystals, which may pre-date the growth of the gem or feathers (sub-planar groups of fluid inclusions). The presence of inclusions, especially those which are eye-visible, may have a significant impact on the quality and value of a stone, especially in near-white diamonds. They do not have the same effect in most coloured stones, which are valued mostly for that property rather than for their clarity.

Calcite inclusion in emerald, photographed by Pat Daly.

Desirable Gemstone Inclusions

Some inclusions are desirable because they prove the natural origin of a stone, provide evidence of treatment, or help to decide its geographical origin. Some inclusions which serve these purposes are common and well-known to gemmologists. Horsetail inclusions, ‘rain’ and ‘tiger stripe’, for example, need no further details to specify their nature or the gem varieties in which they are found. Others are so uncommon that a gemmologist may rarely or never have the opportunity to see them. Examples of these are described below.

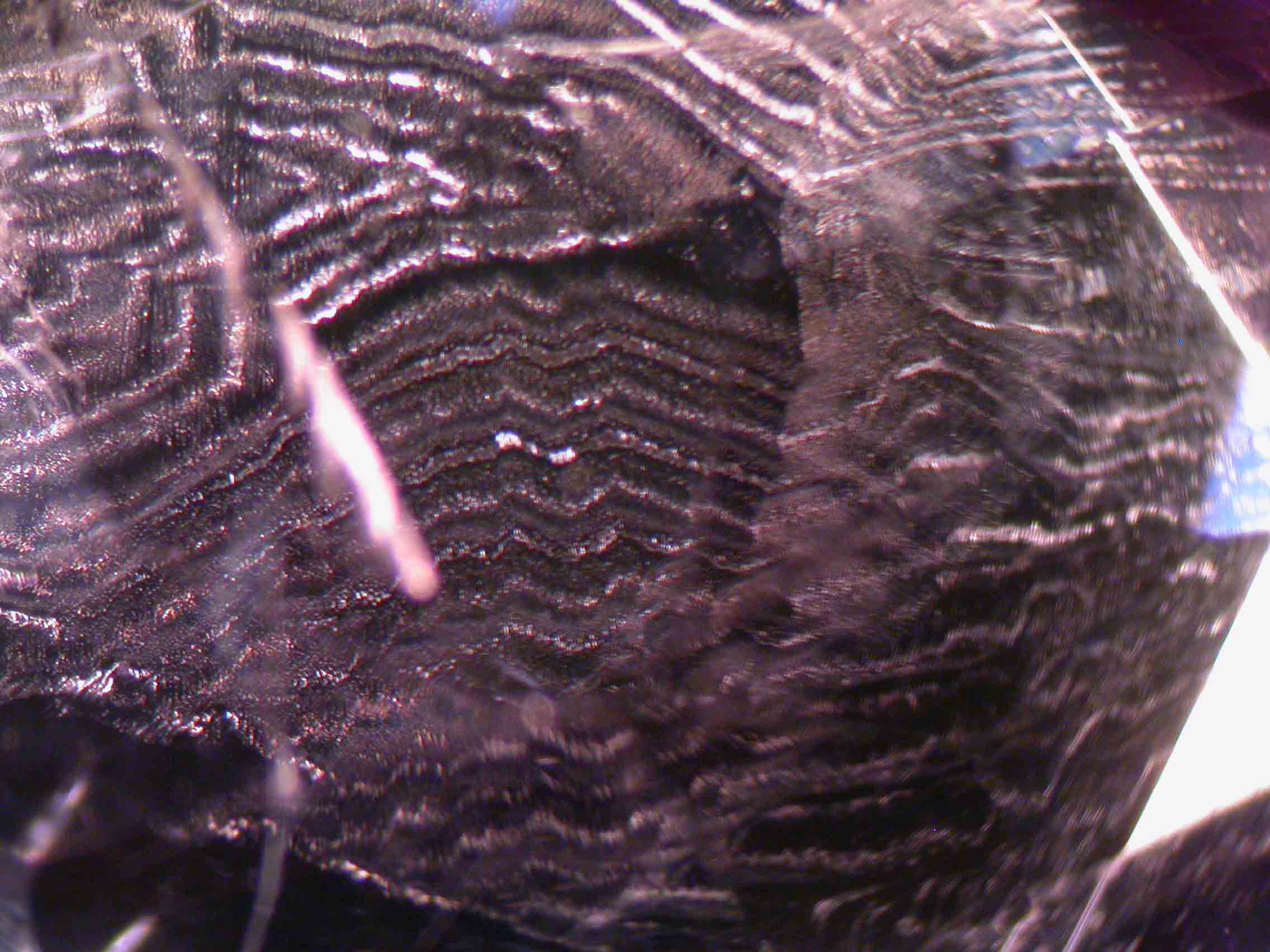

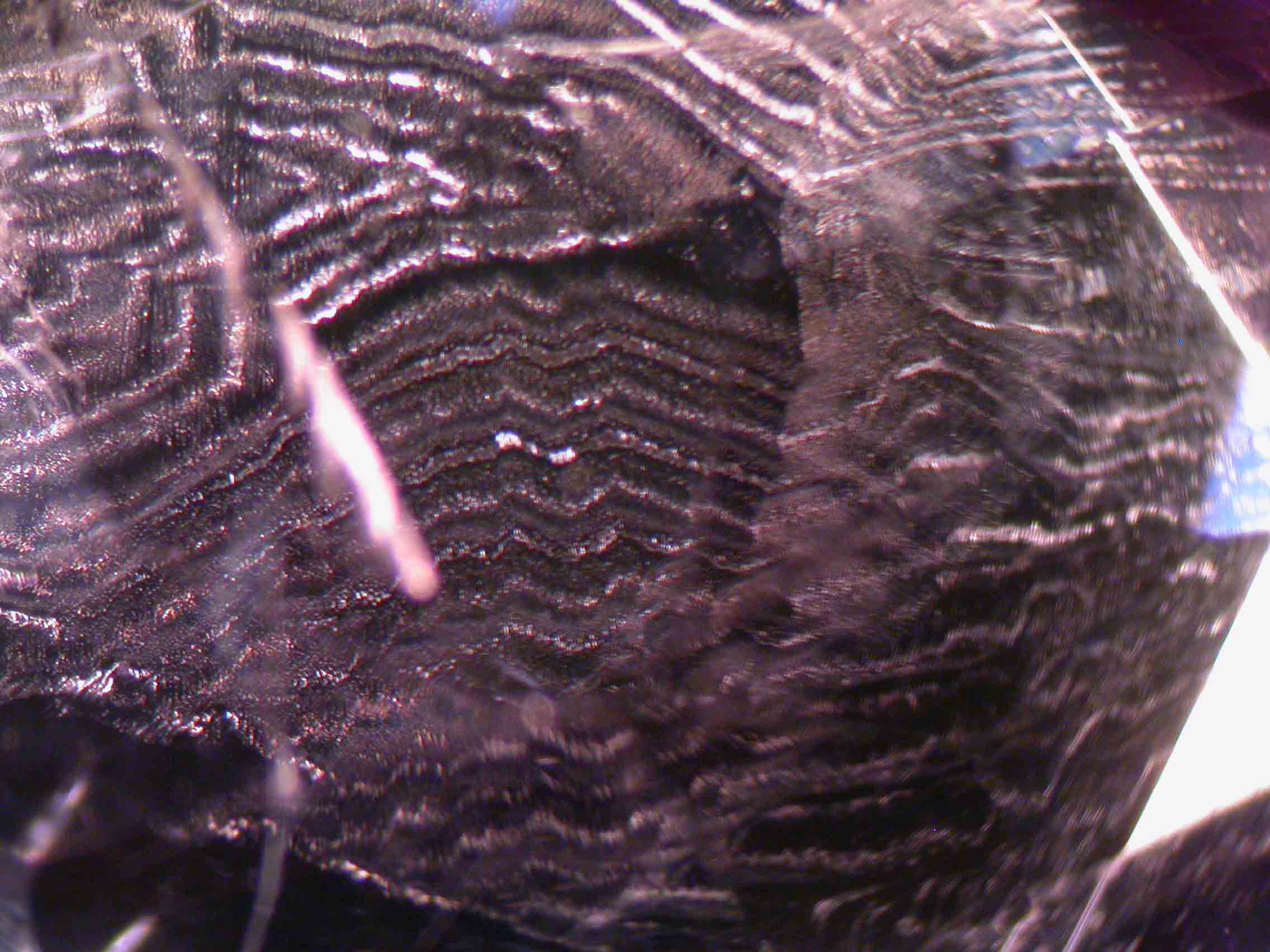

Tiger stripe inclusions in amethyst, photographed by Pat Daly.

Ruby Crystals in Diamond

Bright red crystals in diamonds are usually chrome-bearing pyrope garnets. Gem-quality diamonds are thought to grow in peridotites and eclogites in the lithosphere and mantle beneath continents at depths ranging from about 200 to 800 Km. The very rare occurrence of ruby is linked to eclogites, one of the rock types in which gem diamonds grow, together with other rare inclusions of rutile, coesite (high-pressure silica), and blue kyanite. All are rare and, if they could be identified, would bring pleasure to an enthusiastic gemmologist.

Inclusions in diamond, photographed by Henry Mesa.

Parisite in Emerald

‘Rare earths’ are a group of chemical elements that include cerium, europium, and yttrium. Rare earth is an early mining term for this group of elements, which have similar chemical properties. They are known to gemmologists mainly because of the distinctive spectra of some gemstones which contain them, especially apatite. Rare earths are commonly present as trace elements in minerals, but those in which they are essential components are rare. Parasite, a carbonate of cerium and other elements, occurs at Muzo in Colombia and is sometimes present as brown crystal inclusions in emeralds from that locality. Some emeralds containing it display a rare earth spectrum. It is not common as an inclusion, but its presence proves the natural and geographical origin of the stone.

Black spinel inclusions in emerald, photographed by Pat Daly.

Tourmaline in Kashmir Sapphire

Kashmir is famed as a source of fine-quality sapphires, though more abundant stones of lower quality have been found there. Many gemmologists see good-quality stones infrequently and would be lucky to see tourmaline crystals as inclusions. Transparent green crystals of tourmaline about 3 mm wide are known to occur about a mile from the site where sapphires have been recovered, although they are said to be brittle and of poor quality. Tourmaline inclusions, if their identity can be confirmed, are considered to prove that sapphires are from Kashmir and are, therefore, useful inclusions so long as they do not detract from the appearance of a stone.

Yellow crystal inclusions in sapphire, photographed by Pat Daly.

Animal Fossils in Precious Opal

Amber is widely known as a host for fossil insects and has provided science with invaluable specimens which would not have survived otherwise. Fossils are preserved in other materials, including opal, which may preserve tree roots and twigs. In Australia, opalized fossil shells, bones and occasionally nearly complete skeletons of marine animals have been found. The remains of land animals, such as dinosaurs, mammals and the flying reptiles pterosaurs, are sometimes discovered at Lightning Ridge in New South Wales.

Opalised shell, photographed by Pat Daly.

All animal fossils composed of opal are rare, but the rarest are the most delicate and fragile. A few years ago, a piece of precious opal containing a well-preserved insect was found in a mine in Indonesia. It has been identified as an immature cicada, of which most body parts were recognized and which external features such as hairs and mouth parts could be seen. It is thought to be 5 to 10 million years old and to have been preserved in silica dissolved from the weathering of volcanic glass. Most gemmologists have seen insects in amber and copal resin, but few have or will handle precious opal containing one.

Rare Fossils in Amber

It has been suggested that an animal larger than about 20mm would, in ordinary circumstances, be able to pull itself free from tree resin. If so, it is not surprising that vertebrates are rare fossils in amber. They are known, however. Partial and, very rarely, complete lizards have been found in amber from the Baltic, Dominica and Mexico. Fur, feathers and snakeskin are also reported. Similar, equally rare vertebrate remains are included in Myanmar amber, which is thought to have formed nearly 100 million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, within what is called the ‘Age of Dinosaurs’.

An insect trapped in amber, photographed by Henry Mesa.

One of the most exciting finds of recent years was reported to be the skull of a small dinosaur embedded in Myanmar amber. It is about 14mm long, has a toothed jaw, and is thought to have been an insect eater. Later research on this and another specimen has led to the opinion that it is not a dinosaur or a bird (birds are now considered to be dinosaurs) but a lizard-like animal.

Another recent find is considered to be part of a non-avian dinosaur. It is a feathered tail about 37mm long, the construction of which excludes the chance of it having belonged to a bird. This is perhaps the rarest inclusion in a gem material, at least for the time being, though the impetus it has given to the search for similar fossils may result in further discoveries. Any of us will be fortunate to have the opportunity to study what will always be an almost vanishingly rare inclusion.

Main image: Natural comma shaped inclusions in emerald, photographed by Pat Daly.