Do you know your calcite inclusions from your dumortierite, epidote, fluorite and rutile? Here, Charles Bexfield FGA DGA EG explores some incredible quartz inclusions and explains what to look for when shopping for quartz specimens.

Silicon is the second most abundant chemical element in the earth’s crust after oxygen. The two elements combine to create silicates for example, feldspars, amphiboles and pyroxene, to name the larger groups, as well as silicon oxide (SiO2), also known as quartz. Quartz is found on every continent.

Read more: Exploring the Varieties of Quartz

There are three main ways quartz forms: hydrothermally, in hot watery conditions under varying high temperatures and pressures; as pegmatites in igneous rocks from superheated liquids under pressure similar to hydrothermal formation; or in silica rich molten rock (magma) which has cooled slowly allowing the solution to crystallise as quartz instead of forming natural glasses.

Read more: Understanding Iridescence in Gemstones

The majority of inclusions in quartz form in hydrothermal conditions, especially in Brazil. In these conditions, silica is usually the last mineral to form after rarer, more reactive elements in the crust bond with each other or with silica groups, forming other minerals until only silica remains, which grows in the remaining spaces.

Some pockets of hydrothermal activity can produce single crystals of quartz weighing hundreds of kilograms, again, usually in Brazil due to the cooler temperatures allowing more time for crystallization. Single crystal quartz forming in pegmatites can also encapsulate other minerals.

Read more: Highlights of the Gem-A Gemstones & Minerals Collection

Due to the abundance of quartz it isn’t among the most valuable stones even in fine quality. However, to collectors and now some modern jewellery retailers, quartz with inclusions can command a premium, especially if the quartz is encapsulating rare minerals, which may only form as smaller crystals, for example, dumortierite.

Below is an alphabetical list of inclusions you could possibly find in quartz and a little bit about each one:

Quartz Inclusions: Brookite

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) forming in the orthorhombic crystal system. The longer needle-like crystals found in quartz usually are usually black to grey, however they can have a brownish colour with larger crystals which are prismatic in form.

Quartz Inclusions: Calcite

Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) growing in the trigonal crystal system. When found as inclusions in quartz they are usually rhombohedral in shape but can show a bi-pyramidal form too. Colours can vary with the possibility of most colours being found. Colourless is most common and easily found when viewed through crossed polars.

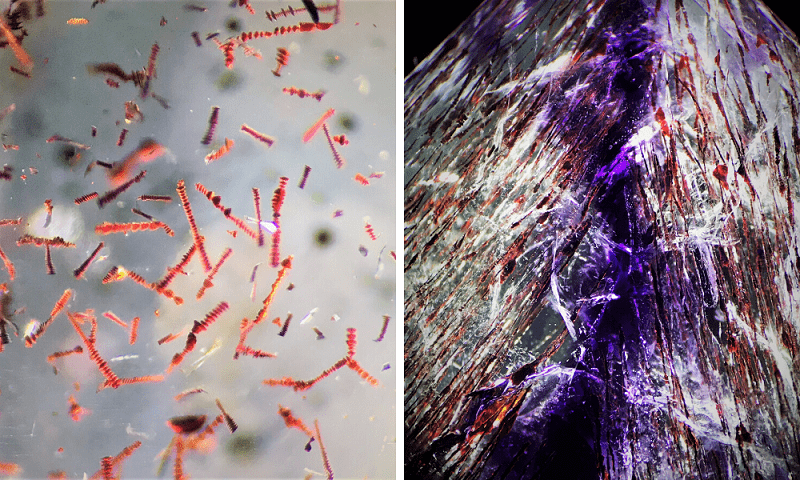

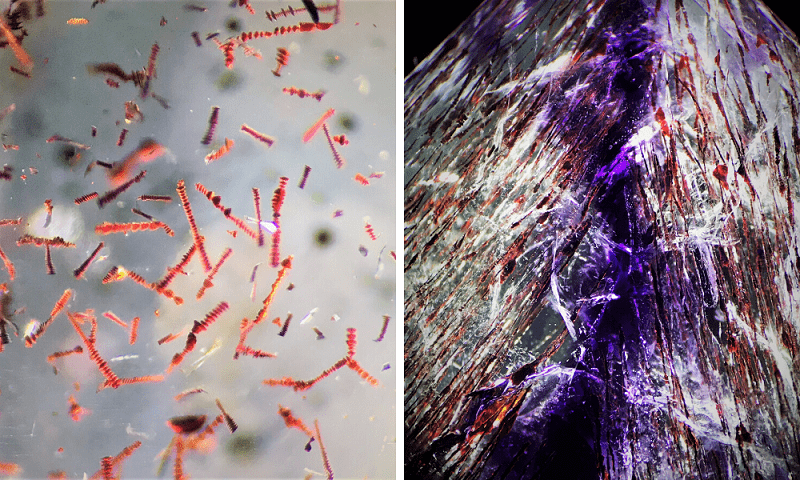

Red rutile and calcite in quartz. Photograph by P. Daly.

As with the picture above, other minerals can be seen overgrowing the calcite, however the form of the crystal is still visible. Reddish rutile is seen intersecting the calcite in this example.

Quartz Inclusions: Dumortierite

Dumortierite crystals form in the orthorhombic crystal system as bladed, prismatic crystals usually as radiating fibrous aggregates; sometimes these crystals form abundant groups (photograph on the left) as well as well-formed specimens (photograph right). Crystals bigger than an inch are rare.

Read more: What Should Be in the Ideal Gemmologist’s Toolkit?

Usually blue in colour, dumortierite can also be a greenish-blue, purplish-blue and pink. It is very pleochroic, however magnification is recommend to see this as the crystals are so small. These inclusions are very popular among collectors.

Quartz Inclusions: Epidote

Calcium Aluminium Iron Silicate {Ca2}{Al2Fe3+}(Si2O7)(SiO4)O(OH) forming in the monoclinic crystal system. The crystals usually have a prismatic form. Commonly green in colour with hues of yellow and brown. Epidote can also be black and they can vary in size as inclusions. Pictured below is a pleasing example with larger crystals.

Quartz Inclusions: Fluorite

Calcium Fluoride (CaF2) can be found in any colour but when formed within quartz the blue and purple colours are more common. Growing as a cubic material, fluorite usually forms as cubes or octahedrons with strong colour zoning throughout the crystal.

Fluorite in quartz. Photos by C. Bexfield.

Read more: What Makes a Gemstone Rare?

When placed under long wave ultra violet light the fluorite will usually fluoresce against the inert quartz.

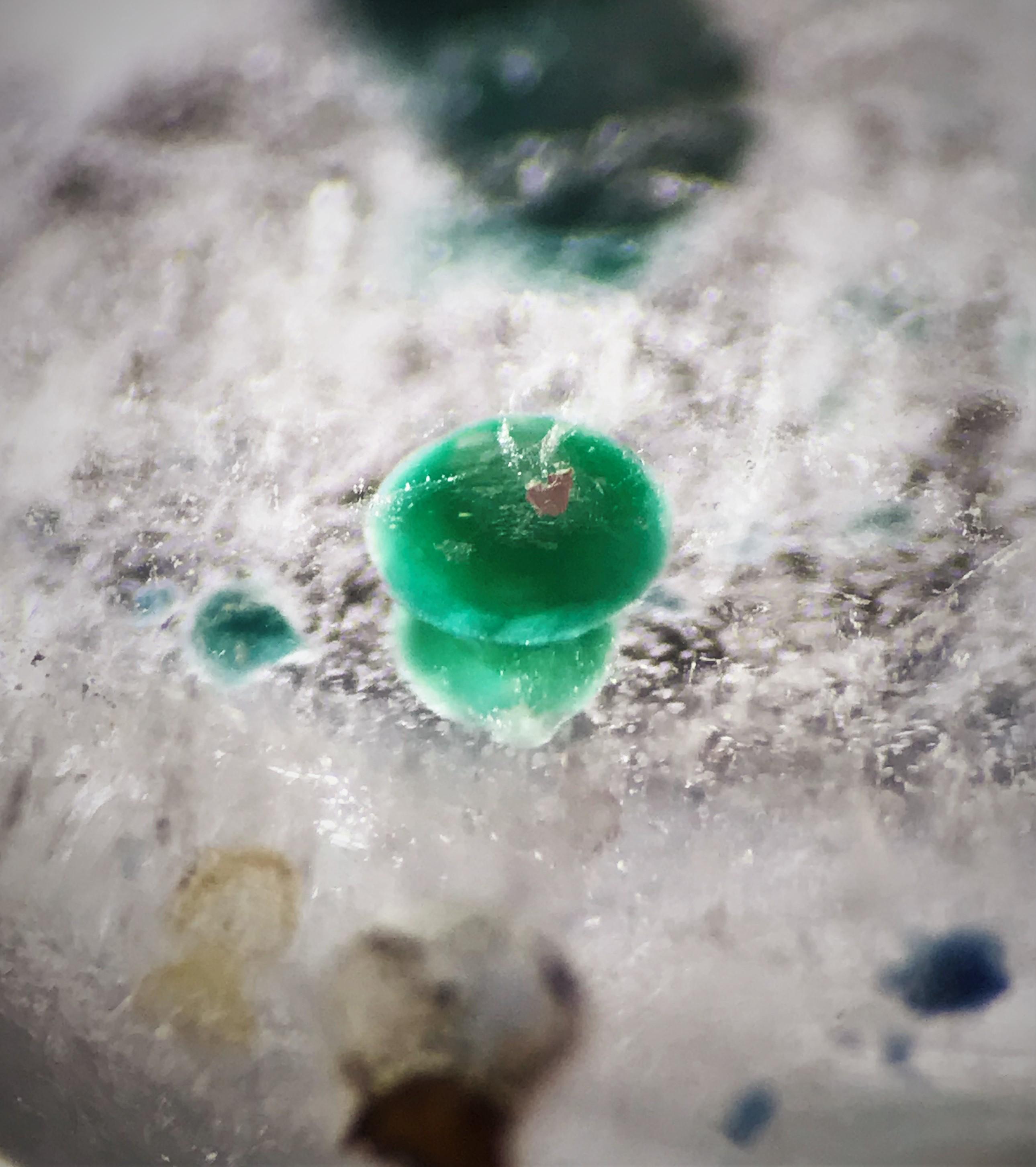

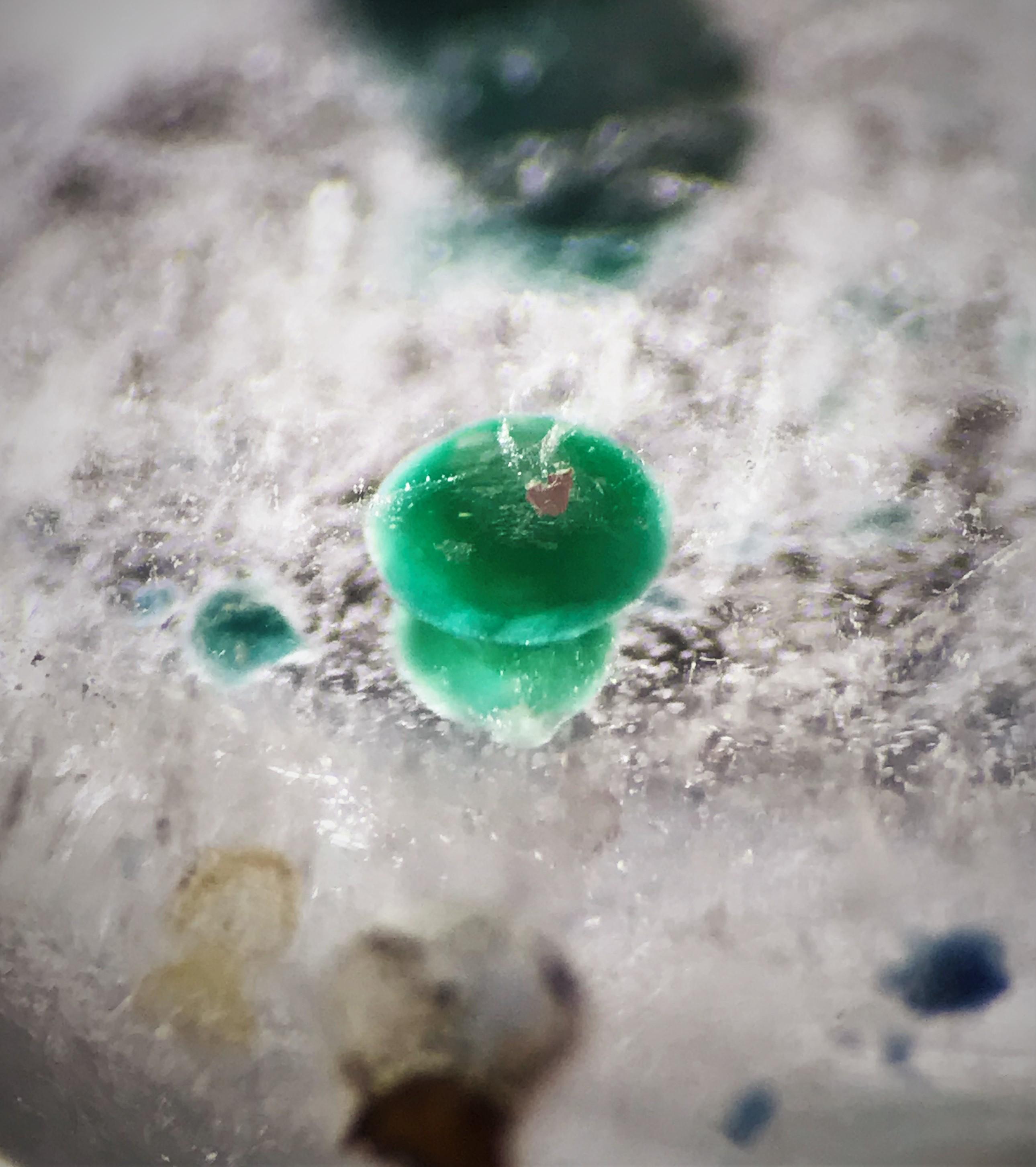

Quartz Inclusions: Gilalite

Copper silicate grows in the monoclinic crystal system, but usually showing no crystal form and instead this mushroom-like appearance. Gilalite is green to greenish-blue. An uncommon inclusion and nice examples can fetch a premium.

Gilalite in quartz. Photo by C. Bexfield.

Quartz Inclusions: Hematite

Iron oxide (Fe2O3) forming in the trigonal crystal system, with a red to greyish metallic appearance. Hematite’s form can be quite variable from platy inclusions to, ‘rose’-like crystals to the ‘coiled’-like crystals photographed below. The more unusual forms are popular with collectors.

Quartz Inclusions: Lazulite

Magnesium Aluminium Phosphate (MgAl2(PO4)2(OH)2) blue, bright blue, greenish-blue to bluish-white in colour. Forms in the monoclinic crystal system and has a prismatic habit, sometimes with pyramidal terminations and usually short, stout crystals. One of the less common inclusions in quartz.

Quartz Inclusions: Piemontite

Piemontite {Ca2}{Al2Mn3+}(Si2O7)(SiO4)O(OH) is a red to reddish violet coloured mineral, but sometimes it can have a brown or black tone as well. Usually formed as radiating bladed crystals. The crystals pictured have been deformed slightly and are no longer showing perfect crystal habit.

Read more: What Career Paths Can Trained Gemmologists Take?

Easily diagnosed from the very strong pleochrosim with the secondary colour being the orange-yellow. A pleasing inclusion to find.

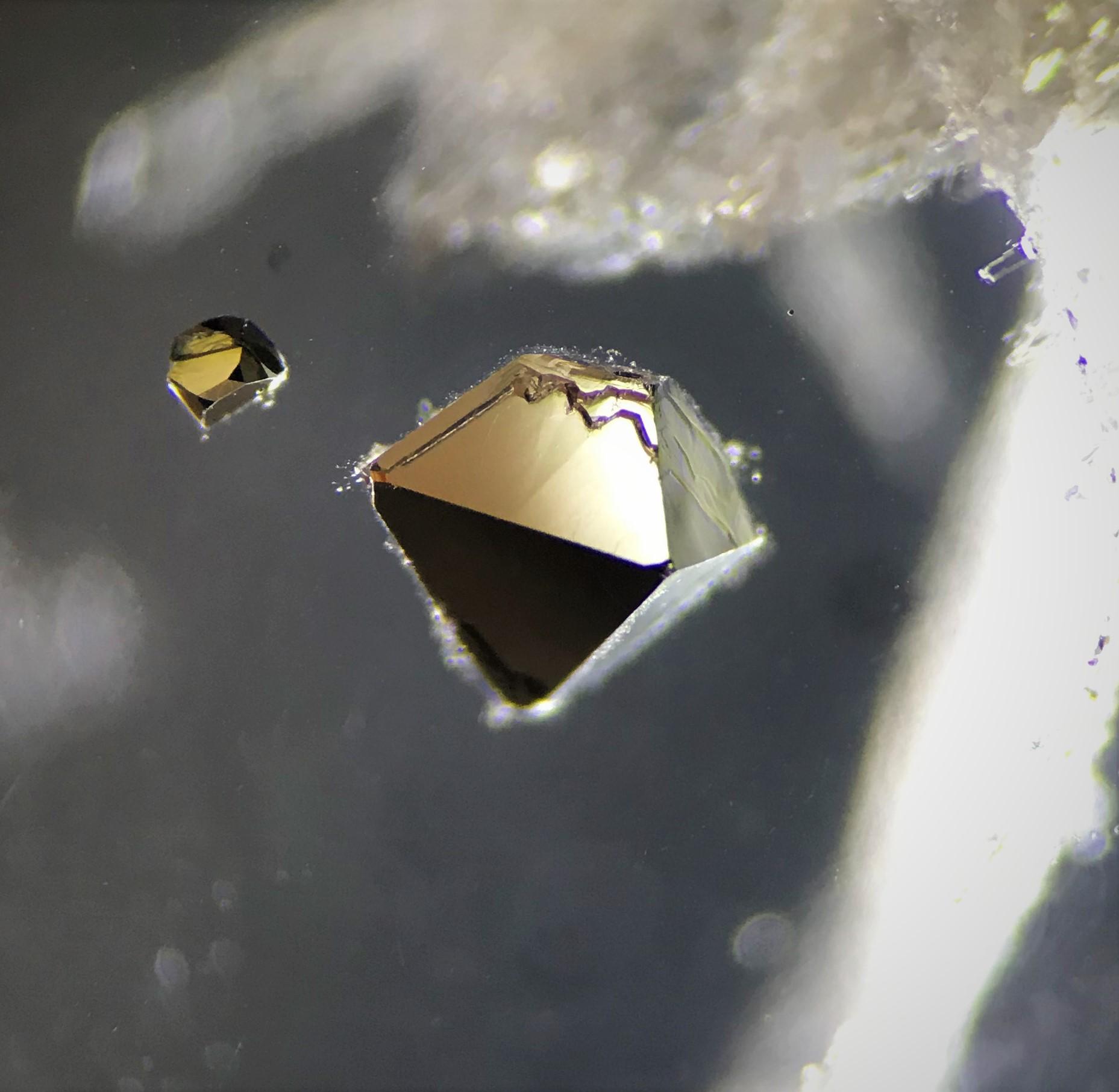

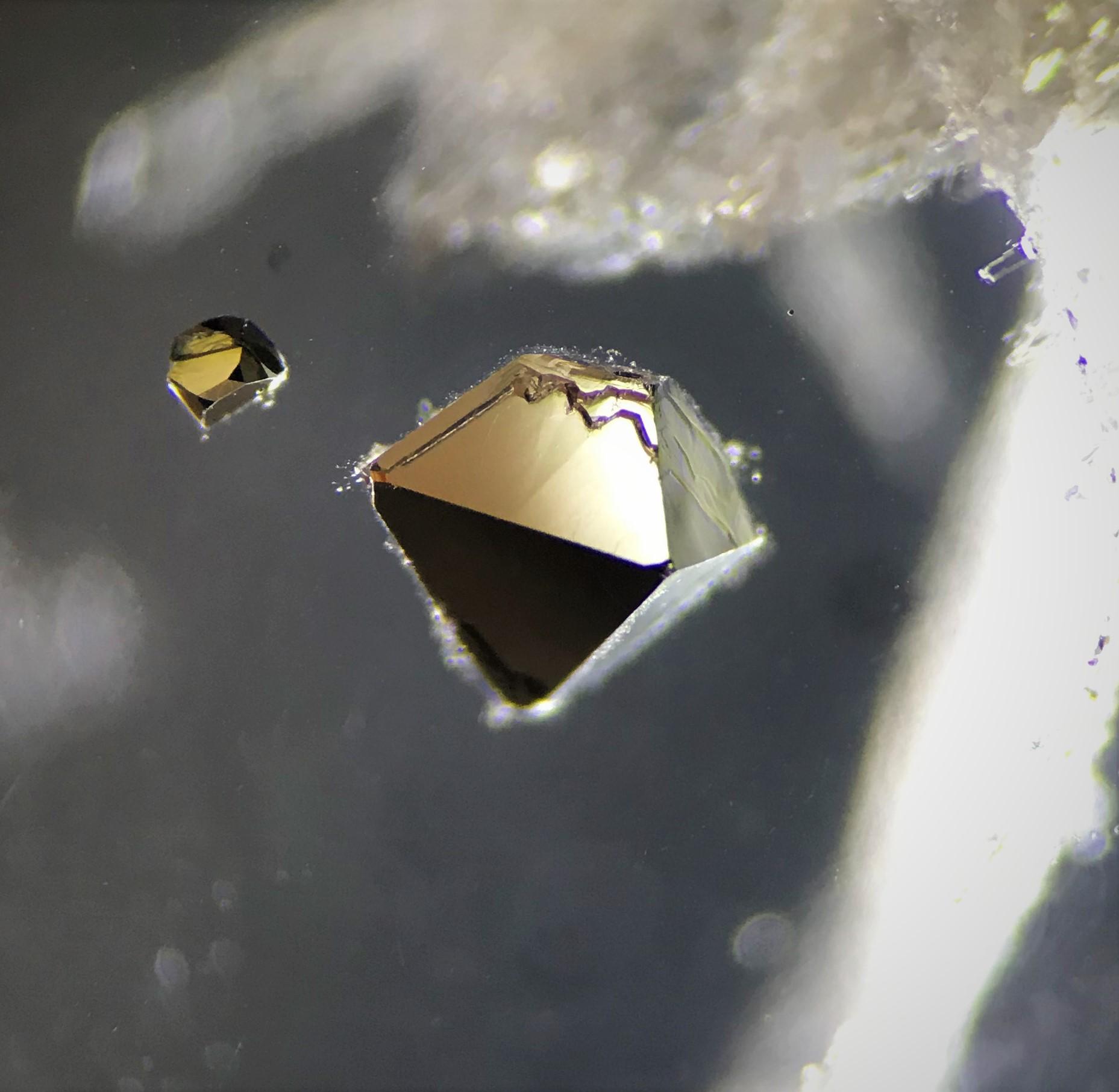

Quartz Inclusions: Pyrite

Pyrite is one of the more common inclusions in quartz. It’s an iron sulphide (FeS2) and occurs in an opaque yellow to brownish-yellow coloured mineral with a metallic lustre. Forming in the cubic crystal system it usually forms a cubes and commonly twins. Pyrite less commonly forms as octahedrons, which can be seen pictured below.

A pyrite octahedron in quartz. Photograph by C. Bexfield.

Quartz Inclusions: Rutile

Rutile, a titanium oxide (TiO2) forms in the tetragonal crystal system as prismatic needle-like acicular crystals. One of the most common inclusions in quartz. With colours ranging from yellow to brownish-yellow, which are the more common colours, and deep red to brownish-red, which are less common and therefore more desirable. Rutile stars are very sought after.

A more common inclusion in quartz and not always expensive, the more elaborate examples sell well.

Secure your copies of Gem-A’s two magazines, Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology by visiting Membership.

Start your gemmology journey today by attending one of our Short Courses or Workshops.

Cover image: Intersecting brookite inclusions in quartz. Image by C. Bexfield.