December 2017: An Update from the Author

No matter how much any information has been checked prior to publication, it is always possible that – sooner or later – some facts are proved incorrect. An author may be contacted by a person who has read an article and has more information on the subject, and of course with time new research often uncovers new details that were simply not available when a book or an article was written.

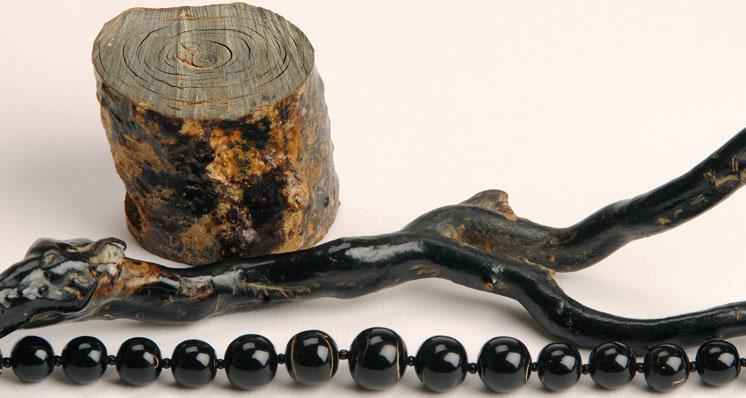

Whitby jet comes into the latter category as it has been the subject of research in recent years. We have long believed it to derive from the wood of one species of tree only (a species of Araucaria), but now research proves that it in fact derives from half a dozen or so tree or plant species. As yet nothing has been published about it, but we look forward with great anticipation to a paper on the subject. It is exciting news, and means that most of the accepted gemmological texts will need to be re-written. The updated knowledge does not, however, diminish the quality of good Whitby jet which is still of the highest order: very uniform, homogenous, deep black, and it takes a very high polish.

Since writing about corals in the Autumn issue of G&J, more information has come my way from Italy about the condition of the coral beds in the Mediterranean. I am assured that they are healthy, and that the fishing is now so tightly controlled by licencing and fishing methods (scuba diving only, size of coral permitted to be harvested, quota and permitted areas), that Corallium rubrum can be traded without a danger of over-fishing. These corals grow in deep waters, so are also less affected by changes in the sea temperatures and pollution. It is good to know that the situation is controlled and that we may continue to enjoy precious coral, but, as with all gem materials, I would always advocate buying only from a reputable source.

——————————————————————-

A Connection to Coral: Gems&Jewellery Autumn 2017 Vol 26 No.3

Coral may not inspire the same emotional outpouring as ivory, but its delicate ecosystem needs to be protected, says Gem-A president Maggie Campbell Pedersen FGA ABIPP.

Coral has a long and rich history. Red coral has been found in Neolithic graves and two thousand years ago was much sought-after by the Chinese. The Ancient Greeks preferred black coral, while in some African countries red coral beads signified wealth. Few gem materials have been believed to have such powers as coral, both talismanic and medicinal. For example, it was thought that coral could cure madness, could strengthen babies’ teeth, and that it turned pale when worn by someone who was sick. A piece of coral above the door of a house would protect its inhabitants, or its wearer from being struck by lightning.

Coral use today is more limited and consists of some jewellery and carvings. It does not have the same emotive impact as some other organic gem materials (notably ivory), yet it is understood that corals are vital to marine eco-systems and that they are threatened, and it should perhaps be remembered that they are animals, not plants – albeit tiny headless ones (called polyps).

The coral used in past times in Europe was predominantly the red Corallium rubrum (often termed ‘precious coral’ by the gem trade), mainly from the Mediterranean. In recent years we have used several different species of coral, originating from many different seas and oceans.

World-wide, coral beds are diminishing. Each species of coral needs different conditions to flourish, but all of them are extremely sensitive to alterations in the temperature of the water and in the acidity of the sea. Our coral fishing methods have been refined and we are far more aware of the risks of over-fishing, but the threats to corals of global warming and pollution remain, and many believe that corals are still being over-fished.

1: Different colours of Corallium corals.

Most corals consist of a white core – the ‘communal skeleton’ – made of calcium carbonate in the form of aragonite or calcite. They are covered by ‘flesh’ which consists mainly of tiny polps connected to each other by living tissue. In most corals the tissue also contains algae called zoolxanthellae with which the corals live in a symbiotic relationship. It is the algae that give the living corals their wonderful colours. In only a few of them is the calcium carbonate ‘skeleton’ coloured (1).

Global warming is causing ocean temperatures to rise, which can result in ‘coral bleaching’ – a phenomenon where large areas of corals reject their vital algae (zooxanthellae) and consequently die off, losing their coloured fleshy covering and leaving just the white skeletons. Corals grow very slowly – some at a rate of a few millimetres per annum – so it takes from 10 to 20 years for a reef to regenerate. As coral bleaching is today happening more often it is becoming less likely that the corals can recover, hence the worry about the Great Barrier Reef off Australia’s north-east coast, and also the reefs around Belize.

The phenomenon affects reef corals because they grow in shallow water, however, of our gem corals only blue coral is a reef coral, and all other gem corals are either solitary or colonial in habit. They live on the seabed and grow at greater depths where they are less vulnerable to changes in the water temperature. Despite this, they are still sensitive to the raised acidity of the water and rising sea levels caused by global warming, and to all pollutants that find their way into the oceans. A further risk to their survival is physical impact which breaks them, for example caused by fishing nets, or divers. But perhaps their greatest threat has been over-fishing for the gem trade.

Corallium corals grow in colonies, and have a tree-like appearance (2). They range from white through shades of pink, salmon, and blood red to deep red. There are several Corallium varieties, of which C.rubrum is the best known. The Latin names of a number of the others are at present being changed – a frequent occurrence with corals. The colour in Corallium corals is in the hard skeleton, as they lack zooxanthellae.

2: Unpolished branch of Corallium rubrum showing the tree-like shape.

The coral is recognised by the tiny striations along its ‘branches’, which are still visible after cutting and polishing as they penetrate the entire skeleton. They are about 0.25-0.5 mm apart. The material takes a very high, porcelaineous polish (3).

Corallium coral is found in the Mediterranean and around Japan, China, and other areas of the Pacific. Fishing is now being regulated in several of these areas due to extremely depleted coral beds, and the rarity of the material is reflected in its price. It has been suggested that some Coralliums should be included in the CITES Appendices (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), but this has not happened as the trade prefers to regulate itself. Methods being used include rotating areas where fishing is permitted, specifying the amount and minimum size of coral taken, the number of licenses granted, and the equipment used.

3: Detail of Corallium rubrum beads, showing structure and high lustre.

Torre de Greco (on the outskirts of Naples in Italy), has been a famous centre for coral carving for hundreds of years. Today the large companies cannot rely entirely on local coral to meet demand, so make up the shortfall – about 30%- from the Far East. The Mediterranean raw material is generally smaller in size, so larger items are carved from the Far Eastern material.

Several years ago at gem fairs such as those in Tuscon, bamboo coral (of the family Isididae), was sold in abundance, but today we see only small amounts for sale. A beige colour in its natural state, it is bleached and dyed, usually red or orange. It is a heavy material, and although the outer surface displays longitudinal striations similar to Corallium corals also have a growth habit resembling that of a tree, but they have nodes of organic material called gorgonian between the internodes of calcium carbonate. These characteristics limit the coral’s use, and it is most commonly seen sliced into discs and used as beads, or as simple carvings. Occasionally it is seen imitating Corallium coral. It has been so popular that the coral beds are now severely depleted (5).

4: Bamboo coral: natural coloured rough, dyed rough, and dyed beads.

Heliopora coerulia or blue coral is found in many parts of the Indo-Pacific region and in the Great Barrier Reef. It appears on CITES Appendix II, indicating that it is permissible to trade but only under very strict conditions, and licences are required. It is a reef coral with a blue aragonite skeleton – one of only two reef corals with a coloured skeleton – and is massive in form rather than tree-like. It is covered in tiny holes in which the polyps lived (6).

6: Blue coral, Heliopora coerulia: rough and polished beads.

Some years back another red coral began to appear on the gem market: Melithaea ocracea. It is often called red sponge coral. It belongs to the family of soft corals, which create a less compact skeleton. Though it is still rigid, it is less stable as a gem material and is usually impregnated with a resin to stabilise it and to enable it to be polished to a satin finish. The resin also makes it much more comfortable to wear as it is a very rough material in its untreated state. It is naturally a red colour in the beige veins. It is found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and the China Seas (7).

7: Melithaea ocracea: polymer impregnated disc, colour enhanced beads (inner row) and reconstructed (chips in a red polymer, outer row).

Black and golden Antipatharia corals are found around the Philippines and Indonesia. They are also listed on CITES Appendix II. They differ from other corals in that their skeletons are made up of organic matter (closely related to keratin), not of calcium carbonate. Although flexible when growing, the material becomes rigid after fishing (8).

Golden corals are rare, but black Antipatharia can be bleached to a golden colour, and is often sold as a natural material. Once popular at gem fairs in the form of loose beads, black or bleached material is still occasionally encountered today, and is generally sold as ‘old stock’.

There are other coral not mentioned here that can be used for jewellery or objets d’art, and not all are listed by CITES – often because they have not been adequately researched. It is incumbent upon the buyer or seller to check a species’ status, which can be problematic as coral is notoriously difficult to identify when it has been cut and polished.

In the EU, licences must be obtained (e.g. from APHA, the Animal and Plant Health Agency in UK), for any corals that are listed by CITES on Appendix II. Each request is considered individually with many criteria taken into account. Other countries have different guidelines, sometimes stricter than ours, for example the beautiful Kulamanamana haumeaae golden coral from Hawaii is not listed by CITES, but is protected by US law.

8: Black Antipatharian coral, genus Leopathes: rough, and polished beads.

Some coral jewellery is still sold at the high-end of the market, beautiful items are still being produced in coral in the Far East, and there is still a coral industry around the Mediterranean, but generally not nearly as much coral is being worked today as in times past, partly due to fashion, partly due to the rarity of raw material, and partly because there are many people who feel that corals are too endangered and vulnerable should not be fished.

Attempts have been made at culturing corals, but so far it is a tiny industry, targeted mainly at the aquarist market where small corals are a popular addition to tropical fish tanks. Gem corals grow too slowly to make it a feasible alternative to wild-caught corals.

We do not emotionally equate the use of coral with that of ivory, but corals play a significant role in marine ecosystems and need to be protected, and failure to do so will eventually result in a total ban. Meanwhile the gem trade should ensure that any coral purchased is reliably sourced.

Gem-A members can log in to read the full article Gems&Jewellery Autumn 2017 / Volume 26 / No. 3

Interested in finding out more about gemmology? Sign-up to one of Gem-A’s courses or workshops.

If you would like to subscribe to Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology please visit Membership.

Cover image: Corals for sale at the Tuscon fairs in 2008. All images ©Maggie Campbell Pedersen.

{module Blog Articles Widget}