Diamonds belong to the cubic crystal system

When you first start learning about diamonds, you will discover that these carbon-based gems belong to the cubic crystal system. Diamonds can be unearthed in numerous forms that belong to this system. Here, Gem-A Gemmology Tutor Pat Daly explains more about the shapes of diamonds.

All crystals belong to a small number of major groups called the seven crystal systems. Diamonds belong to the cubic system. Crystals in this group tend to be compact, with ideally shaped examples having the same dimensions in three directions at 90° to each other. Diamond may be found in several forms belonging to the cubic system, for example cubes, octahedra, and dodecahedra.

Diamond Crystal Shapes: Octahedra

When they grow deep in the Earth, mostly at depths between about 150 and 200 kilometres, they almost always develop as octahedra, rarely as cubes. Diamonds which occur in other shapes usually do so because they have been partially resorbed. This is where part of the diamond crystal is dissolved, transforming what was once a perfect octahedron into a striated and etched shape. If enough resorption takes place, a diamond crystal may eventually become spherical.

The shape of this diamond has been changed by resorption. The yellowish colour of the stone is caused by the presence of nitrogen. Photo from the Gem-A Archives.

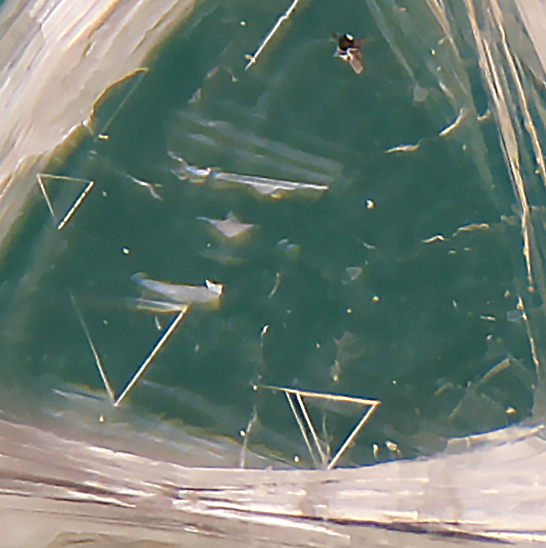

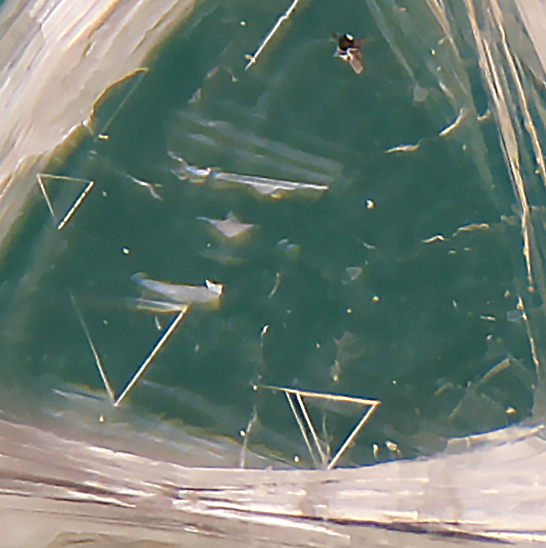

They crystallize under certain conditions in which temperature, pressure and rock chemistry are favourable for their growth. Changes in these conditions during the hundreds of millions of years during which most diamonds remain within the Earth, or while they are being transported to the surface by volcanoes, may result in the crystals starting to dissolve, changing their shapes and, usually, producing rounded corners, edges and faces. These processes commonly result in distinctively shaped triangular pits, called trigons, which may be found on nearly all octahedron faces of diamond.

Trigons on the surface of a rough diamond crystal from the Gem-A Archives.

Some crystals retain the shape of an octahedron, with sharp edges and flat, lustrous faces which look as though they have been polished, even though they have developed naturally. Others are rounded looking, fissured and distorted. Some stones are highly irregular in outline, having little resemblance to the geometrically perfect shapes of some octahedra. Some of these irregular diamonds are large and are of rare types which are almost free from nitrogen, the commonest chemical impurity in diamonds, which causes an unwelcome yellowish colour in most stones. They are valuable gems, some of which are thought to have grown at exceptional depths of 600 to 700 kilometres.

A rough diamond of dodecahedral shape from the Gem-A Archives.

Diamond Crystal Shapes: Twinned

Diamond crystals may be twinned. This means that different parts of their atomic structures have different orientations, which might be reflected by their external forms. The commonest type of twinned crystal is triangular and rather flattened looking and is called a macle. Evidence of the twinning consists of notches (re-entrant angles) at the corners of the crystals, and V-shaped markings close to them.

Twinning may occur so that two triangular macles are joined to form a six-pointed crystal called a star twin. Some flat looking triangular crystals are untwinned, despite their resemblance to macles. Another, rarer type of twinned crystal consists of two cubes which are interpenetrant, so that the corners of one project from the faces of the other. To imagine this, think of two crystals that have grown into and out of one another!

These types of twinning probably began during growth. A different type, called repeated twinning, results from distortion of the crystals in the hot, high-pressure conditions of the mantle. It causes parallel twin planes across which a direction of the atomic structure changes. Diamond is the hardest known material and cutting relies on differences in its hardness in different directions which are related to its atomic structure. Changes in direction caused by twinning make the skilled process of polishing diamonds more difficult.

Diamond Crystal Shapes and Diamond Polishing

Diamond polishing results in a loss of material because it is a process of abrasion. The most popular style of cut is the round brilliant, which displays the desirable features of brilliance, sparkle and fire to best effect. Cutting round stones from sharply angular octahedra involves a loss of about 50% of the original weight. Cutting them from other crystal shapes may involve even higher losses and it may be preferable to choose a different style or shape of cut to minimise the loss.

A perfect octahedral rough diamond from the Gem-A Archives.

A triangular crystal, for example, may be better fashioned as a pear-shaped or trilliant cut stone, and other shapes could be used to produce princess or emerald cut diamonds. One of the preliminary stages of diamond polishing is designing, and factors such as the weight loss which would be incurred by different cut styles are considered at this time.

Rough Diamond Crystals in Jewellery

Some diamond crystals are attractive enough to be used in jewellery without polishing. The effects of fashioning on the appearance and value of a rough diamond are such that it will almost always be carried out on good gem quality crystals, but those of lower quality, which might not qualify as gems in the ordinary course of trade, may have bright, clean faces, appealing shapes and interesting colours. They may be drilled so that they can be strung on necklaces or set in pendants and earrings, or claw set in rings and other styles of jewellery.

The attractiveness of some crystal shapes, which could not be used to produce standard cut styles, may be exploited in this way. For example, thin, flat crystals and hopper types, on which faces are concave and the crystal seems to consist of radiating, thin plates, may add a great deal of visual interest to a piece of gold or silver jewellery, at relatively modest expense.

Main image: Rough diamond crystal photographed by Pat Daly.