Gem-A's History

Learn more about the history of The Gemmological Association of Great Britain, from its formative years in the early 1900s all the way through to today.

Our Story

Since 1908, Gem-A has been at the forefront of gemmological education. Learn more about our story here.

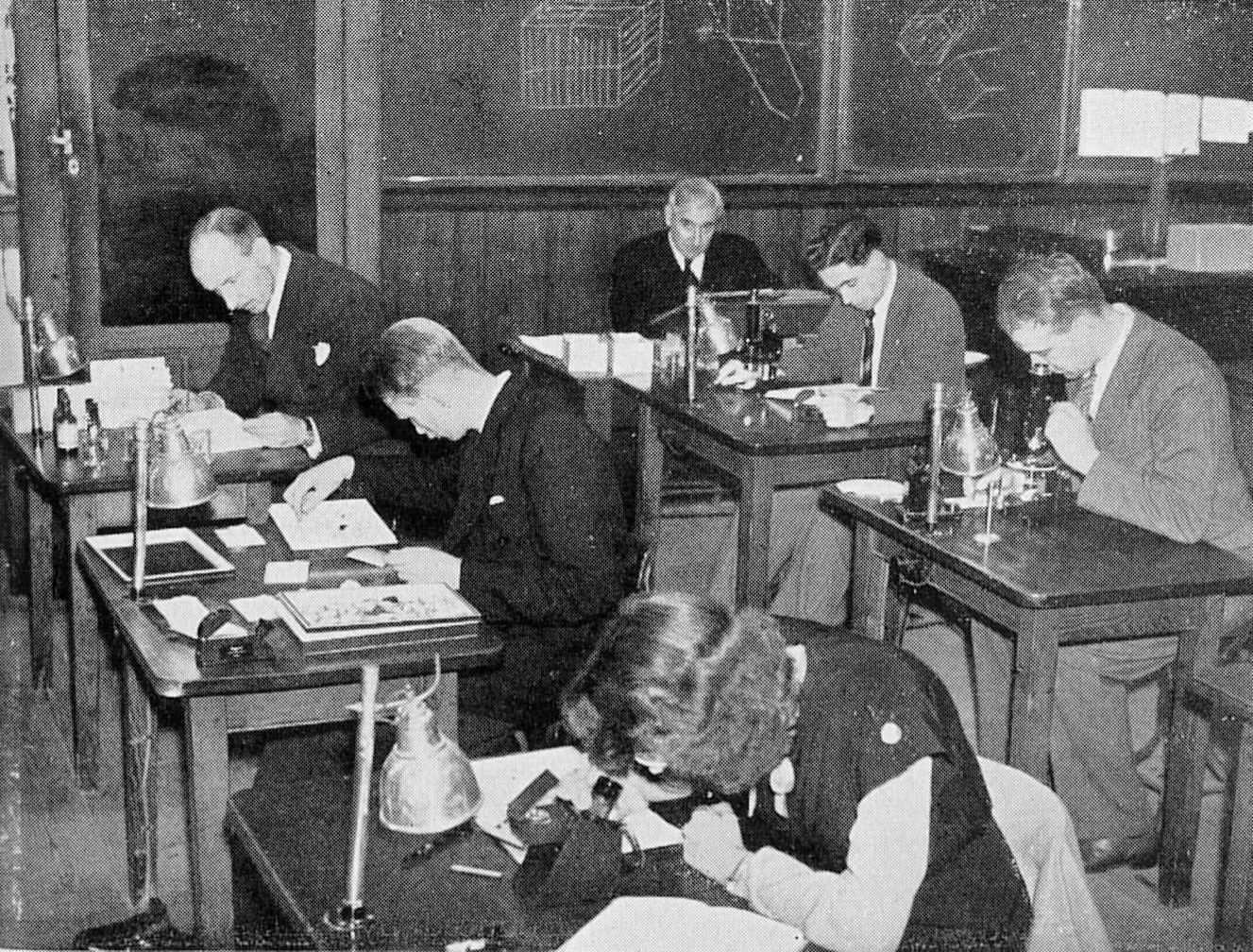

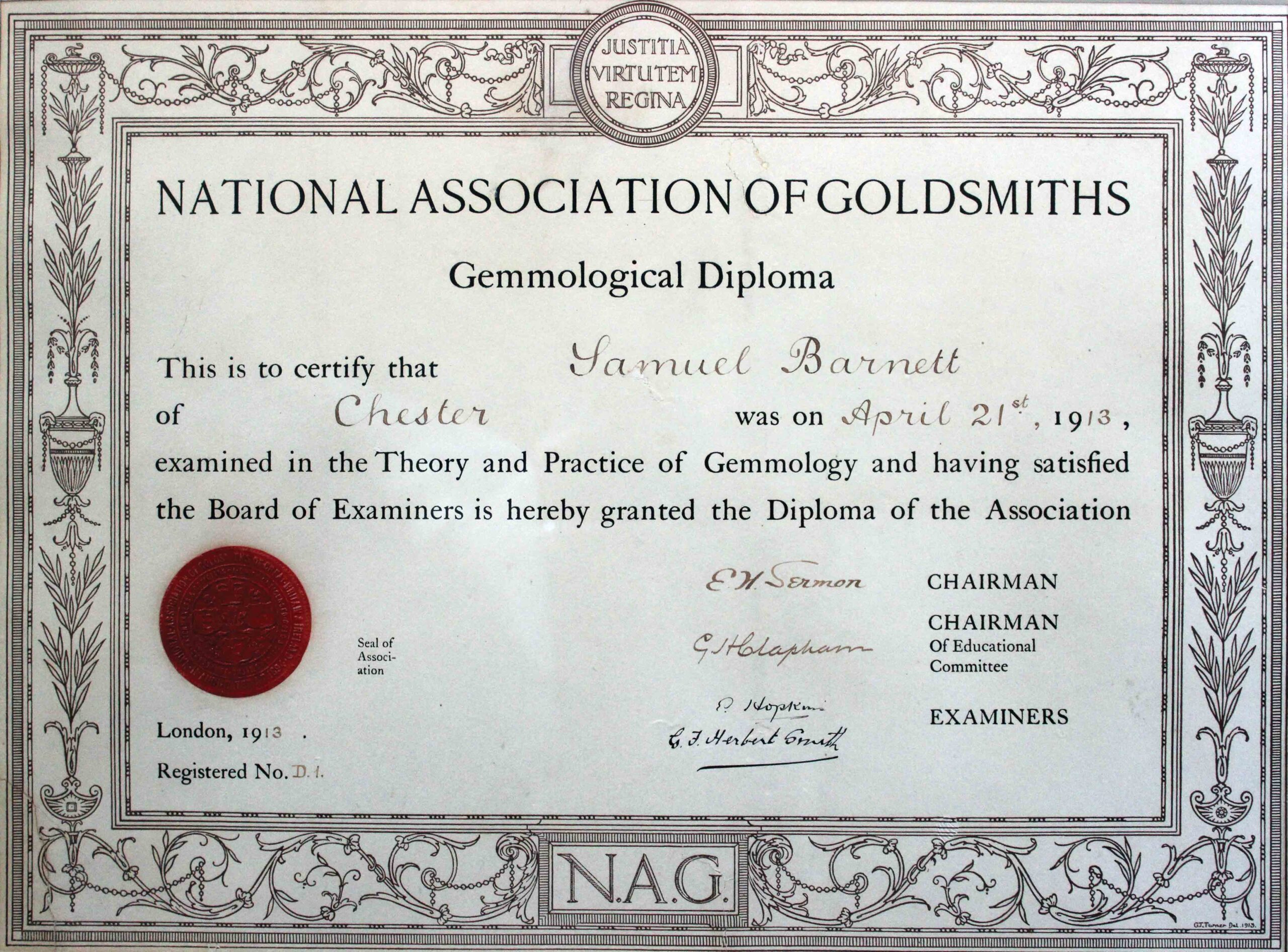

In 1908, the National Association of Goldsmiths (NAG) established the NAG Education Committee to introduce gemmological qualifications for UK jewellers. This pivotal move was initiated by Samuel Barnett, a jeweller, and marked the inception of organised gemmology worldwide.

Then, in 1931, the Gemmological Association emerged as a distinct branch of NAG, fostering independence in education, research, and information provision. Interest in gemstones burgeoned over the following decades, prompting connections with global associations eager to teach the renowned Gemmology Diploma. Then, in the mid-90s, Gem-A evolved into a UK Education Charity.

Presently, Gem-A maintains Samuel Barnett’s legacy, providing world-renowned gemmology education while uniting a growing global network of gem enthusiasts and jewellery professionals. Explore more of Gem-A’s history through the timeline below.

1908

1913

Samuel Barnett passes first ever gemmology diploma.

1931

Gemmological Association officially created.

1947

First Journal of Gemmology issue published.

1958

The Association establishes The Sir James Walton Library.

1987

2013

2018

2022

Today

OUR MOTTO

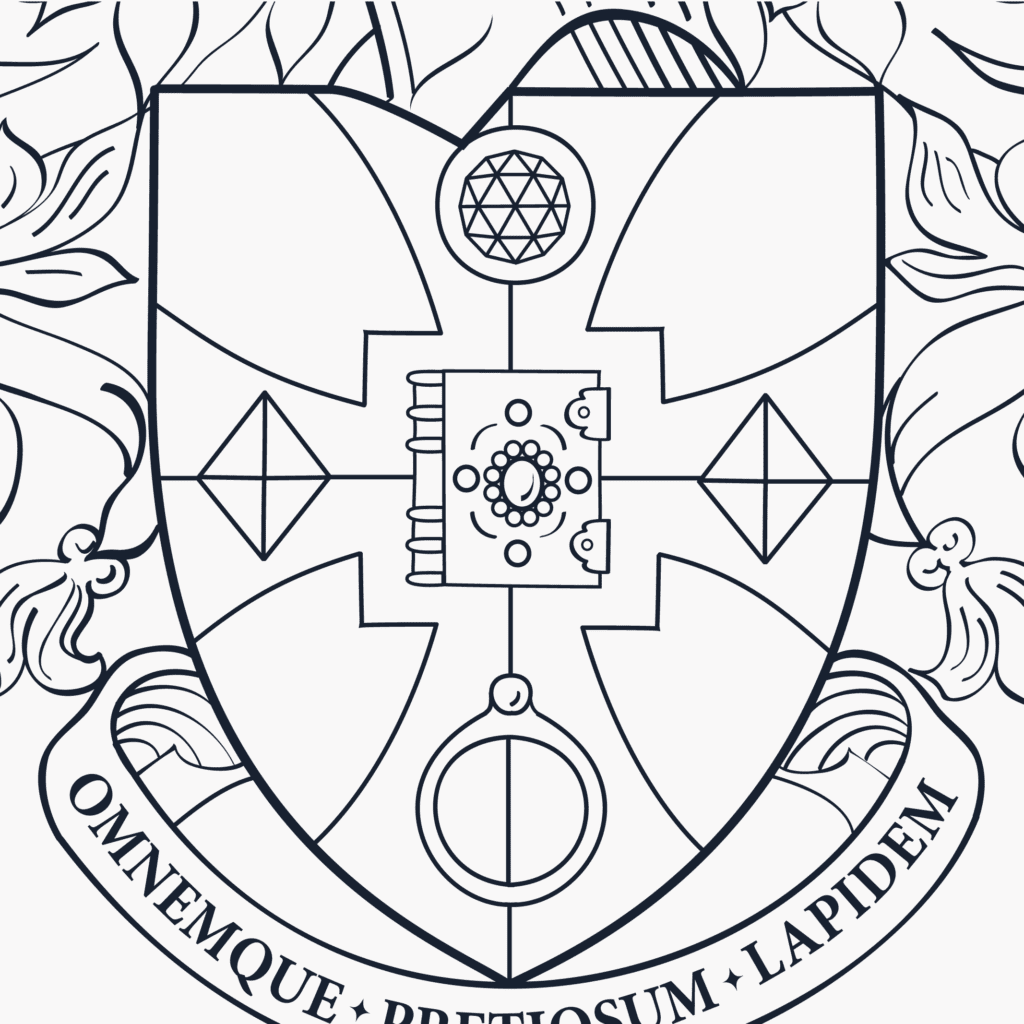

"Omnemque Pretiosum Lapidem"

Every Precious Stone

From 1 Chronicles 29:2

“I prepared all manner of precious stones”

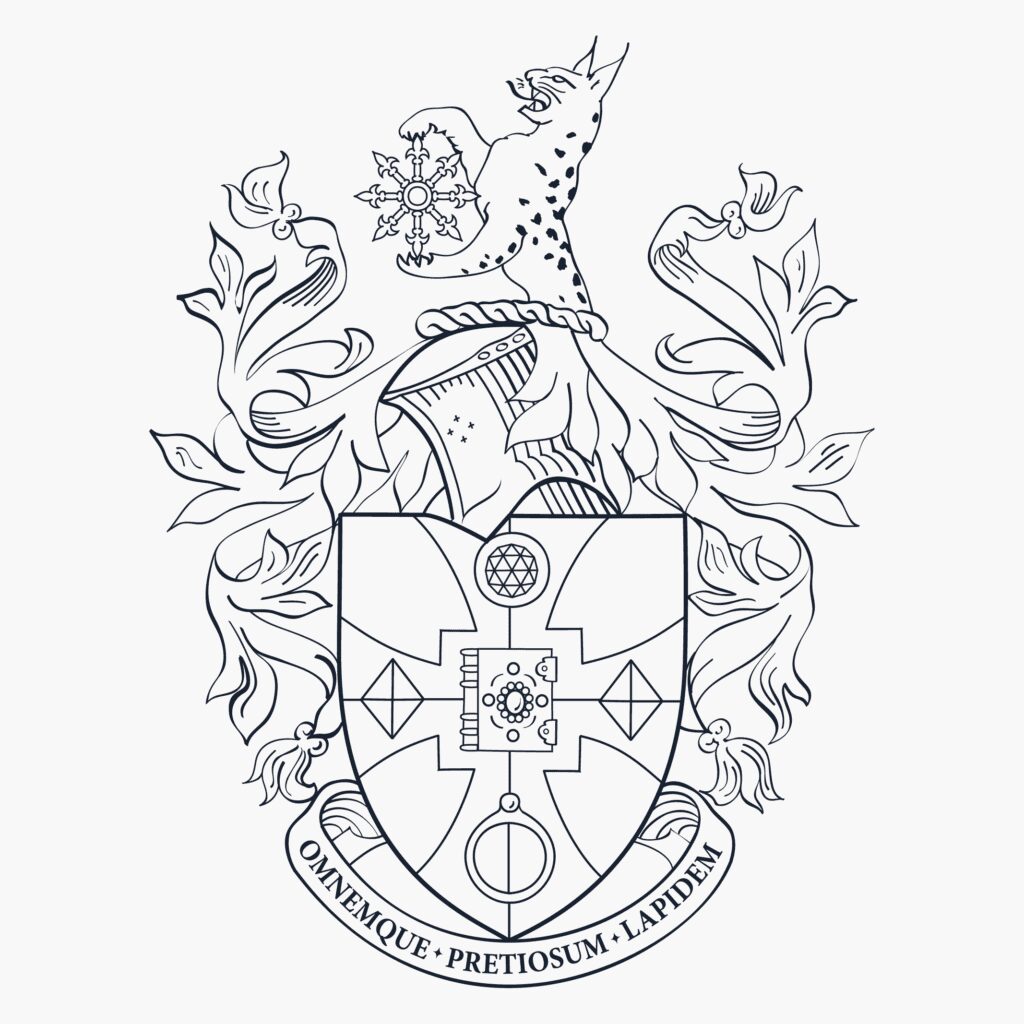

The Coat of Arms

In 1966, the Association made an application to the Earl Marshal and Hereditary Marshal of England for a grant of Armorial bearings, based upon a design prepared by H. Ellis Tomlinson, M.A.

The application was accepted and given below are details of the interpretation of the heraldic form of the design. The right to a Coat of Arms conferred by a grant of arms, made by the Kings of Arms under the Royal Authority, is a limited right, defined by the limitations in the patent, and not a right that the granter can pass onto a third party without express permission.

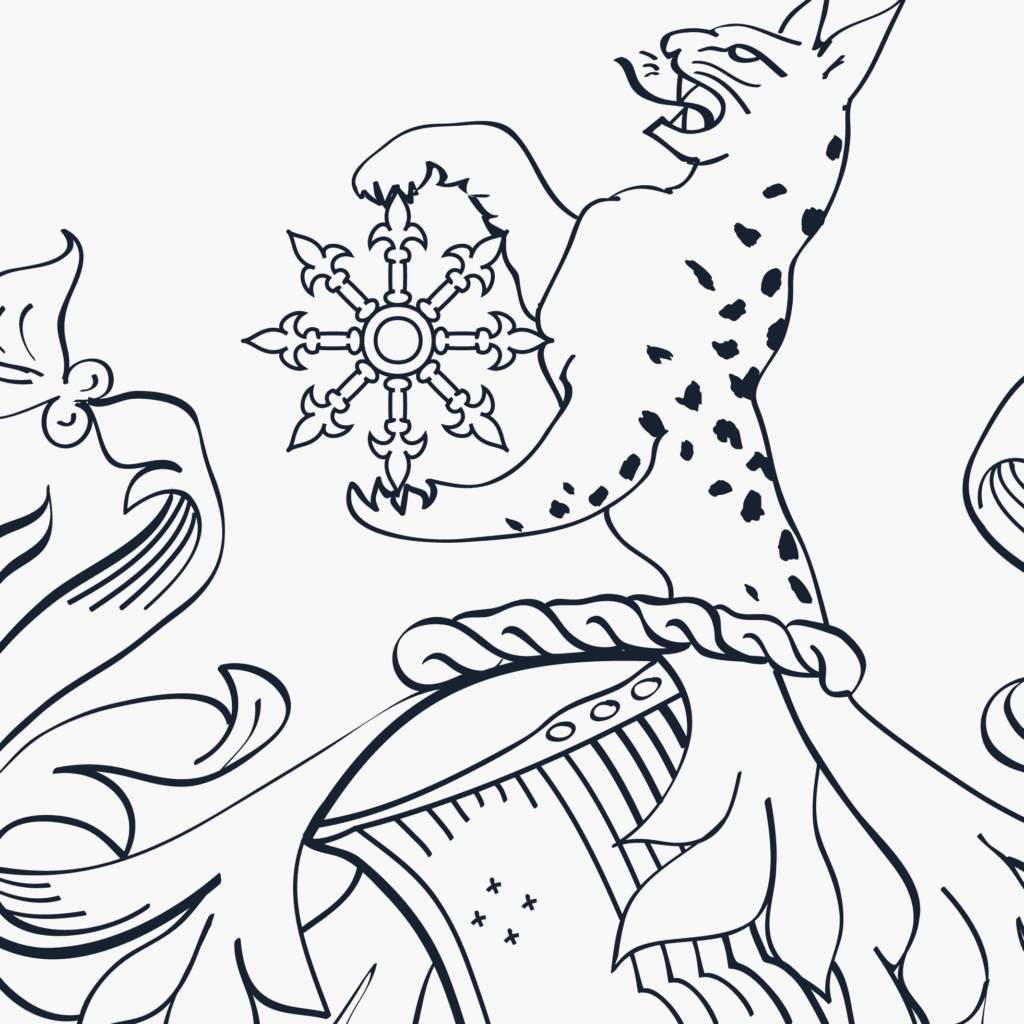

Crest

The lynx is renowned for his keenness of sight and perception, and in ancient times was credited with the faculty of seeing though opaque substances. He represents the lapidary and the student scrutinising every aspect of gemmology.

In his paws is one of the oldest heraldic emblems, an escarbuncle. This is said to represent a very brilliant jewel, usually a ruby. The radiating arms suggest the light it defuses. The escarbuncle is, as it were, heraldry’s special emblem of gemmology. It is often shown with the fleur-de-lis at the tips, and the pommels round the rays in a different colour, from the rays and the central jewel.

Shield

The cross is quartered red and blue, like the associational arms of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and the National Association of Goldsmiths. In the middle is a gold jewelled book, which represents the study of gemmology and the examination work of the Association.

Above it is a top plan of a rose cut diamond inside a ring, suggesting scrutiny of gems by magnification under the lens. The lozenges represent an uncut octahedra, and the gemmed ring indicates the use of gems in ornamentation. The colours of the shield are mainly the national red, white and blue, which also covers the main range of gems.

Looking to the future

Today, the Gem-A coat of arms signifies its unwavering commitment to its history and heritage, standing as a mark of honour and a reminder of the progress The Gemmological Association of Great Britain has made over the past century, and we continue to display our heraldry with pride to this day.