Although all diamonds are special, there are some that are historically significant, spectacularly large and hugely important for gemmological research. Here, Rona Bierrum FGA DGA EG pinpoints the five diamonds that stand out from the crowd for gemmologists the world over.

Type into any internet search device ‘Famous Diamonds’, and a litany of posts will appear, each claiming to be the definitive list of the world’s ‘Top Ten Famous Diamonds’.

So why are we adding ourselves to these ranks? Because we have a slightly different focus and interest, which we know our gemmological readers share.

That interest is one of scientific curiosity, inspired by those breakthrough moments in history where great things became possible because a stone appeared and exemplified certain properties. So, let’s investigate the ‘Top Five Famous Diamonds’ that shaped gemmological history!

Famous Diamonds that Changed History

These diamonds are fantastically large and beautifully cut with fabulous brilliance, fire and scintillation. They also have an impeccable historical pedigree and have added to our understanding of diamonds; without them the progress that we have achieved in the science of gemmology would not have been possible.

The Cullinan Diamond

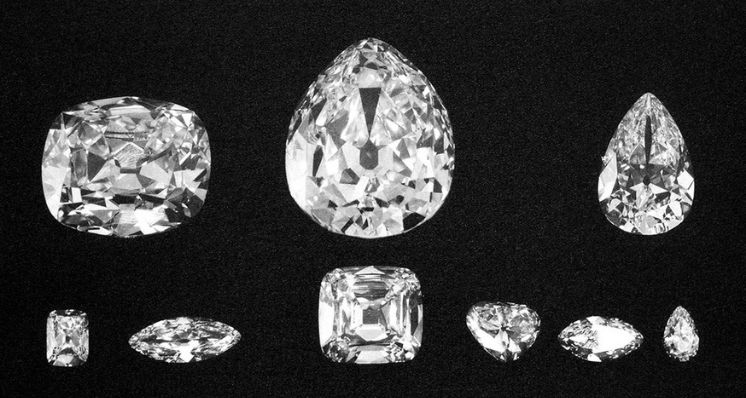

Discovered in 1905 in South Africa, this enormous stone made history by being the largest diamond ever discovered at a rough weight of 3,106ct. The diamond was cut into 105 stones, the two largest of which can be found in the British Crown Jewels at the Tower of London.

The Cullinan I Diamond

Cullinan I, a pear-shaped stone of 530.20cts (mounted in the Imperial Sceptre) and Cullinan II, a cushion shape weighing 317.40cts (in the Imperial State Crown) were inspected by Kenneth Scarratt, Director of the Gem Testing Laboratory of Great Britain (with other gemmologists including Eric Emms and Nigel Israel) in 2005, and were both determined to be Type IIa diamonds (bearing little to no nitrogen, one of the rarest diamond types in nature) with D colour and potentially flawless clarity grades (grades estimated due to mounting restrictions).

A replica of the Cullinan Diamond at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. Image courtesy of James St. John (Creative Commons).

This is significant, as research into ‘superdeep’ diamonds just eleven years later by Smith et al in 2016 demonstrated. Termed CLIPPIR diamonds (Cullinan-like, Large, Inclusion-Poor, Pure, Irregular and Resorbed), these monstrous gems originated from much deeper in the Earth’s mantle than it was originally believed that diamonds could grow.

Read more: A Quick Guide to the British Crown Jewels

By studying inclusion-bearing offcuts, Smith et al proved that these stones formed in pools of iron and nickel at approximately 660km beneath the surface of the Earth. Not only does this discovery aid our understanding of diamonds, but it also helps us to build a bigger picture of the true state of the Earth beneath our feet.

The Dresden Green Diamond

Not much is known of the early years of the Dresden Green, a rare Type IIa pear-shaped natural green diamond housed in the Green Vaults of Dresden in Germany. At approximately 41 carats, it is the largest natural green diamond known and is set in a mounting dating from 1746, converted to a hat ornament in 1768.

We know that the stone was offered for sale to the King of Poland by a London dealer in 1726, and had therefore probably been mined from an alluvial source in India (the only known locality for diamonds at this point in history). In 1988, a team of GIA gemmologists assessed the stone as being VS1 clarity, but potentially flawless with uniform ‘Fancy Green’ colour throughout the stone.

Understanding Green Diamonds

In 1904, the British scientist Sir William Crookes presented his findings on the colour treatment of diamonds to the Royal Society of London. Crookes had buried some Cape colour diamonds with radium salts, initiating a process of irradiation which turned the stones green.

The Dresden Green Diamond – a 41 carat (8.2 g) natural green diamond, which probably originated in the Kollur mine in the state of Andhra Pradesh in India. Here it is pictured as part of a hat clasp ornament. (By ubahnverleih – Own work, CC0)

An example of one of these original treated diamonds is reportedly housed at the British Museum, where it still sets off a Geiger-counter today. Years passed and techniques of irradiating diamonds improved to a stage where they no longer presented a hazard to human health.

Read more: Coloured Diamonds From Least to Most Valuable

In order to learn how to identify whether the green colour of a diamond was natural or not, it was of paramount importance for gemmologists to examine a stone that was absolutely known to have a natural green colour. Because the Dresden Green has a documented history that predates this treatment, it played a crucial role in this study, lending authoritative spectroscopic data for a natural green diamond.

Deepdene Diamond

While we are on the subject of treated diamonds, let’s take a look at the Deepdene Diamond, a stone which has the dubious distinction of being the world’s largest treated diamond. The Deepdene has a documented history which includes the ownership by the Bok family (from whose estate the diamond took its name) in 1900. These records document the stone as being a 104.88 carat light yellow cushion shape.

The Deepdene was sold by Harry Winston in 1954 and just a year later, Dr. Frederick Pough (the contemporary expert in the irradiation and annealing of diamonds) was employed to treat the stone in order to intensify the colour. The diamond was subsequently repolished to its current weight of 104.52 carats.

The Deepdene Diamond Scandal

In 1971, Christie’s London offered this stone for auction, with two gemmological certificates stating that the colour was natural. It was reportedly bought by the jewellery house Van Cleef & Arpels for £190,000.

Prior to this sale, the esteemed gemmologist Dr. Edward Gubelin had raised concerns that the stone was treated. After the sale, the stone was inspected by Basil Anderson and Robert Crowningshield in New York (who had been familiar with the Deepdene in its untreated state). Both of these experts agreed with Gubelin, and the sale was rendered null and void on the grounds of non-disclosure of treatment.

The Deepdene was offered at auction with full disclosure 28 years later (1997) at Christie’s Geneva, where it was sold to Lawrence Graff for $715,320 (including premiums). Supposedly, Graff sold it to novelist Danielle Steel, but its present whereabouts are unknown although there are indications it may have come to rest at one of the Science Museums in Philadelphia.

The Hope Diamond

The Hope diamond is one of the most widely known diamonds on the planet. This 45.52 carat Fancy Dark Grayish-Blue antique cushion cut diamond currently resides in the Smithsonian Institution, to which it was donated by Harry Winston in 1958.

The Hope Diamond Curse Myth

Much of its infamy stems from the belief that the diamond carries a curse and that all owners of the stone underwent grim experiences and came to grisly ends as a result of its ownership. What is not so widely known is that a number of the stories associated with the Hope were invented by Pierre Cartier in an attempt to increase its appeal for sale in 1908.

The Hope Diamond photographed at the Smithsonian Institute by Jessie Hodge (Creative Commons).

The Hope Diamond photographed at the Smithsonian Institute by Jessie Hodge (Creative Commons).

Where the Hope has made gemmological history, however, is in its properties. While we have known for some time that its colour stemmed from the presence of isolated boron atoms distributed throughout its carbon matrix, which also cause its somewhat ominous red fluorescence and long lasting phosphorescence, we have only recently been able to work out how boron managed to reach such low levels in the Earth’s mantle.

Understanding Blue Diamonds

Studies of the Hope along with other boron doped natural blue diamonds have revealed that the presence of this unusual element in diamonds is related to sea water on the surface of our planet. Boron is plentiful in this environment, and highly unusual in the mantle of the Earth. Evan Smith, a GIA research scientist, discovered while studying superdeep diamonds that some inclusions in blue diamonds have both methane and hydrogen as a layer surrounding solid inclusions.

Read more: What Makes a Gemstone Rare?

This pointed them to the presence of hydrous fluids (watery fluids) in the mantle, and they reached the remarkable conclusion that these blue diamonds must be the result of the dragging down (or subduction) of ancient oceans around the crust.

Moussaieff Red Diamond

A list of exceptional diamonds would not be complete without mention of the Moussaieff Red. Although this diamond weighs in at just 5.11 carats, it is the largest diamond ever to achieve the coveted colour grade of Fancy Red. These are the rarest of all known diamonds. In 1987, it was stated that the GIA laboratory had never graded a red diamond which did not have a modifying colour to it. By 2002, there were four. Of these stones, the Moussaieff (graded in 1997) was the largest by at least 2.50 carats, and according to our research, its size has not yet been surpassed.

Understanding Red Diamonds

Red diamonds are just a strongly saturated version of a pink diamond, and the colour in the stones is understood to be caused by the same processes. These processes are a little bit complex. Diamonds have four directions of perfect cleavage. Along these four directions, there are structural weaknesses in the stone (comparatively speaking of course!) because of the way the atomic bonds are orientated.

As a result, when a diamond is struck suddenly in line with these planes, it will break, giving extremely flat breakage surfaces. If massive sustained pressure is applied in a hot environment, these bonds may be shifted along a little, creating what are known as glide planes.

A beautiful example of a red diamond – the 1.14 carat fancy red Argyle Isla, mined at the Argyle Diamond Mine in Western Australia. Image courtesy of Rio Tinto.

What this indicates is that while the stone was in the mantle of the Earth, the rocks making up its home were shifting around it, creating forcefields of pressure while the diamond was still in its hot growth environment. Pink and red diamonds (along with their more financially accessible cousins, brown diamonds) may thereby be seen as demonstrable proof of mantle convection currents – the cause of the tectonic drift of continents. The idea of plate tectonics was only accepted as a theory in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The Moussaieff Red is still owned by Moussaieff Jewellers Ltd., but is occasionally loaned for display. The 2003 ‘Splendor of Diamonds’ exhibition at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. was one of these rare occasions. Such loans are infrequent but offer the chance to see one of the greatest rarities of nature this world has ever seen.

Learn more about the fascinating history and properties of diamond on the Gem-A Diamond Diploma course.

Enhance your skills with the Gem-A Diamond Grading and Identification course.

Cover image: The nine major stones cut from the rough Cullinan diamond. Top: Cullinans II, I and III. Bottom: Cullinans VI, VIII, IV, V, VII and IX. Image: Public Domain.