Jack Ogden FGA looks into the story of the world’s second largest blue diamond, the Mouawad Blue Diamond, previously known as the Tereschenko Blue Diamond.

In the summer of 1984 David Warren, now Senior International Jewellery Director at Christie’s, received a phone call from the auction house’s bank manager with a question: “Do Christie’s sell blue diamonds? Our client has one the size of a pigeon’s egg.”

Mouawad-Tereschenko Blue Diamond

The huge gem turned out to be the Tereschenko diamond, one of the least well known large blue diamonds, and at 42.92 ct, just a shade smaller than the 45.52 ct Hope. It sold at Christie’s in Geneva in November 1984 for a then-record price of $4.6 million to Robert Mouawad and is now called the Mouawad Blue. Unlike the Hope and many of the other famous diamonds, it has lacked a romantic history.

There has been no curse or celebrated Mughal emperor to add notoriety or spice. The Christie’s catalogue, and Lord Balfour in his standard work on the world’s great diamonds, simply notes that the first known appearance of the stone was in 1913 when the Ukrainian Mikhail Tereschenko left it with Cartier in Paris.

Read more: Harrods Unearths 228.31 ct Diamond from its Vaults for Private Sale

In 1915 he instructed them to mount it in a necklace, which was returned to him in Russia before being spirited out of the country again in 1916, on the eve of the Russian Revolution. Then according to Christie’s and Balfour, it passed into anonymous private ownership until it came up at auction in 1984.

Perhaps we can now add some spice, even a curse, to this story, by introducing a French dancer born in the final decade or so of the nineteenth century. She entered the entertainment world under the stage name of Mademoiselle Primrose and by 1911 was performing in Le Théâtre des Capucines in Paris. She was renowned for her attractiveness and, in a rather surreal article on the components of female beauty in Paris that appeared in various American newspapers in late 1911 and early 1912, she was noted as one of the most beautiful of reigning stage beauties in Paris with particular praise for her “most charming chin”.

Suzanne Marie Blanche Thuillier ca 1920

Suzanne Marie Blanche Thuillier ca 1920If Mikhail Tereschenko left the 42.92 ct blue diamond with Cartier in Paris in 1913 he may have encountered Mlle Primrose in that city. This is not such a wild suggestion because in 1924 we hear of a former Parisian dancer named Mlle Primrose, real name Suzanne Marie Blanche Thuillier, who had resided for a time in St. Petersburg, Russia, and who moved in Court circles there. She had left Russia for France just before the Revolution and was the owner of what was described as a 43 ct blue diamond, called by some the ‘Russian Imperial Blue’, and by others (rather bizarrely) the ‘Blue Diamond of Ceylon’.

The newspapers at the time gave myriad origins for the stone, neither verified nor mutually exclusive. It came from the eye of an idol in India; reached Russia in the time of Peter the Great; had been set in the Russian Crown Jewels; had been secretly purchased in London “under romantic circumstances” and so on.

One newspaper even hedged its religious bets and said the gem had “ornamented the finger of Buddha in a Hindu Temple”. Particularly intriguing is a report in a British newspaper that “In April 1912, there were rumours in Hatton Garden that a diamond merchant was walking about with a quarter of a million in his wallet. In fact he had received from his Dutch agents a stone [a large blue diamond] which had been sent from America with instructions to let it fetch what it would.”

This merchant supposedly pieced together the history of gem, found out that it had once belonged to the Russian Imperial family and put out feelers, which reached the then-Czar who sent an emissary to obtain it. Perhaps more about this supposed transaction will come to light, but in the meantime we can observe that a presence on the market in London in 1912 would tie in nicely with Tereschenko depositing a large blue diamond with Cartier in Paris in 1913.

After Mlle Thuillier and her diamond reappeared in France, some newspapers reported that she had been given it by Czar Nicholas as a token of his regard for her; others that it was given to her by “a member of the Imperial Court of Nicholas”.

The latter view was supported by those in the know who vehemently denied, or expressed indignation, at the suggestion that the late Czar gave Thuillier the diamond. Indeed, according to Le Parisien newspaper in June 1924, when directly asked where it came from Thuillier explained “evasively” that strictly speaking she was not admitted to the imperial court, but “frequented assiduously with the gentlemen of the court who occupied the highest positions”. She never claimed that the diamond was presented to her by the Czar. So, if a gentleman other than the Czar gave her the gem, Mikhail Tereschenko is perhaps a potential contender.

Was a gift of the blue diamond the ticket to a new life outside Russia on the eve of the Revolution? She reportedly arrived in Nice in the South of France in 1916 and pawned it there that same year. The diamond had travelled in a secret pocket of her sealskin coat.

Following her arrival in the South of France, Mlle Thuillier’s beauty and attire “made her a spectacle among the many lovely women”. However, she gambled excessively and this “most notoriously extravagant woman in Europe” inevitably got into debt and had to pawn the blue diamond more than once. In June 1924 the diamond was in pawn for 200,000 francs with creditors circling, but there was the expectation that it would be redeemed and available for purchase. Apparently a Parisian dealer had already offered £125,000 and an American woman £200,000.

The Tereschenko or Mouawad Blue Diamond

What then occurred is unclear. There are reports that a Joseph Paillaud of Cap d’Ail, near Nice, had put up collateral of 1,350,000 francs and would take ownership of the diamond if not repaid in full by 9 December 1924. Mlle Thuillier made a plea to the Court and in March 1925 the Civil Court in Nice removed it from Paillaud’s possession.

Apparently Paillaud’s actions equated with acting as a pawnbroker, an activity for which he was not licensed. A police search of his house – named, ironically, Chalet Russe (Russian Chalet) – revealed numerous pieces of jewellery lacking the required hallmarks plus records of transactions that were not properly registered.

Mlle Thuillier might well have predicted Paillaud’s bad luck. A newspaper report in 1929 recounted that she had believed the diamond to be cursed. This may be typical press sensationalism, but some accounts say she was something of a mystic with an interest in the occult and in 1924 was even considering taking the gem back to India so it might be replaced on the statue of Buddha from which it had been robbed. It clearly never made it back to the statue and the last we hear of the large blue diamond is in March 1925, in the custody of the clerk of the civil court in Nice.

The last we hear of the celebrated Mlle Primrose – with her charming chin – is in jail in Nice in April 1929, after several years of dire poverty. Her desperate situation had driven her to forgery. What happened to the large blue diamond from 1925, until it resurfaced at Christie’s Geneva in 1984 is so far unknown, but a French newspaper in 1924 had already commented that the diamond had “undoubtedly not yet finished the cycle of events of its adventurous life”.

Note: The above was compiled from contemporary press accounts from Europe and America. Their lack of accuracy is demonstrated by their confusions and contradictions, so for now this is a tale of the Mouawad-Tereschenko diamond, not necessarily the tale of the Mouawad-Tereschenko diamond ■

This article originally appeared in Gems&Jewellery March/April 2016 / Volume 25 / No. 2 pp. 32-33

Interested in finding out more about gemmology? Sign-up to one of Gem-A’s courses or workshops.

If you would like to subscribe to Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology please visit Membership.

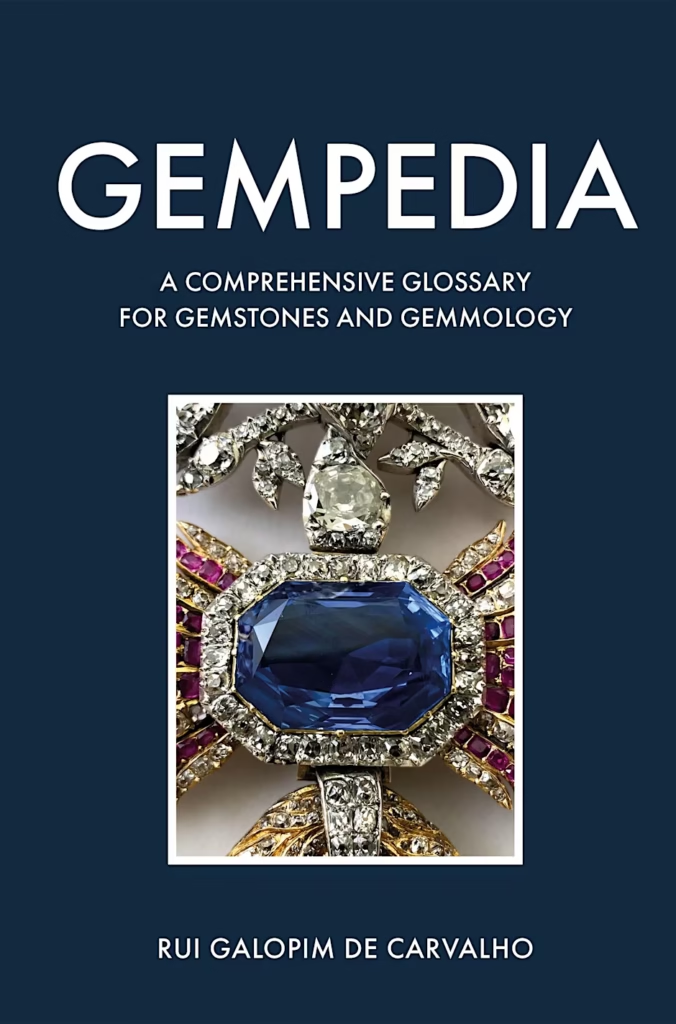

Cover image an exact CZ replica of the Mouawad blue.

{module Blog Articles Widget}