Spectroscopy is the observation or measurement of the absorption and emission of electromagnetic radiation by gemstones. Today, this methodology and its associated tools are vital for gemmologists and can be used to reliably indicate a gemstone’s identity. Here, Gem-A Gemmology Tutor Pat Daly explains more about the history and significance of this scientific technique.

Sir Isaac Newton observed the spectrum of visible light in 1672. In the early 19th century, Joseph Fraunhofer made a spectroscope incorporating a narrow slit to admit light and a diffraction grating to spread out the spectral colours. When he looked at the spectrum of daylight, he noticed dark lines, which are now thought to represent light absorbed by chemical elements in the sun’s atmosphere. These lines are useful to gemmologists when adjusting focusing spectroscopes.

The History of Spectroscopy in Gemmology

The absorption spectra of gemstones were recorded in the 1860s, and those of zircon and almandine appeared a few years later in the book Precious Stones by A.H. Church. The use of the hand-held spectroscope was developed further in the 1930s at the Gem Testing Laboratory in London, and the instrument has become a standard and important piece of gemmological equipment, alongside the refractometer and microscope. It is useful because, in many stones, the positions, widths and intensities of absorption and emission bands are reliable indicators of gemstone identity and, in some cases, natural or synthetic origin and colour treatment.

The same principles apply to other kinds of spectroscopy, though many of them use invisible radiation, and the commercial availability of instruments has had to wait on technological advances. The interaction of infrared with materials, for example, was noticed in the early 1900s, but spectrometers were not marketed until the 1940s. The Raman effect was observed in the late 1920s but could not be utilised until the invention and development of lasers in the 1960s.

Different Types of Spectrometers

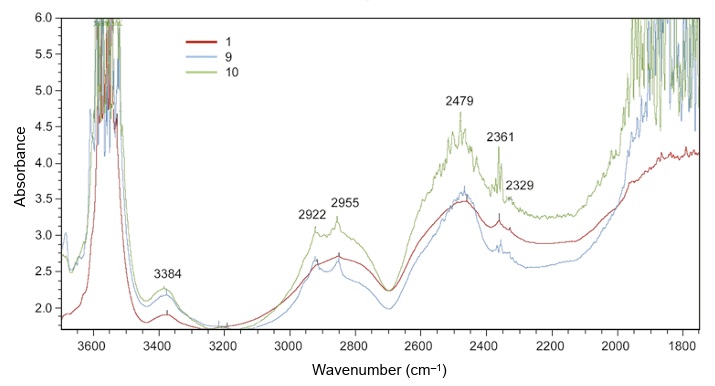

FTIR (Fourier Transform Infra-Red) spectrometers measure the absorption of infrared radiation for different wavelengths (usually expressed as wavenumber, the number of waves per cm). Infra-red wavelengths range from about 700nm to 1mm. Absorption patterns may be used to identify gem materials, distinguish between natural and synthetic stones and detect coatings and filling materials. Diamond types can be recognised, which assists in the separation of synthetic and treated stones.

IA naturally coloured blue diamond, for example, is almost certain to be type IIb, containing boron but no detectable nitrogen, and a near white type I diamond, containing hundreds to thousands of ppm of nitrogen, may be accepted as natural, because most comparable synthetic stones contain less than five ppm. It may be hard for gemmologists to detect the resin impregnation of jadeite by standard tests, but this treatment usually produces distinctive infrared absorption peaks.

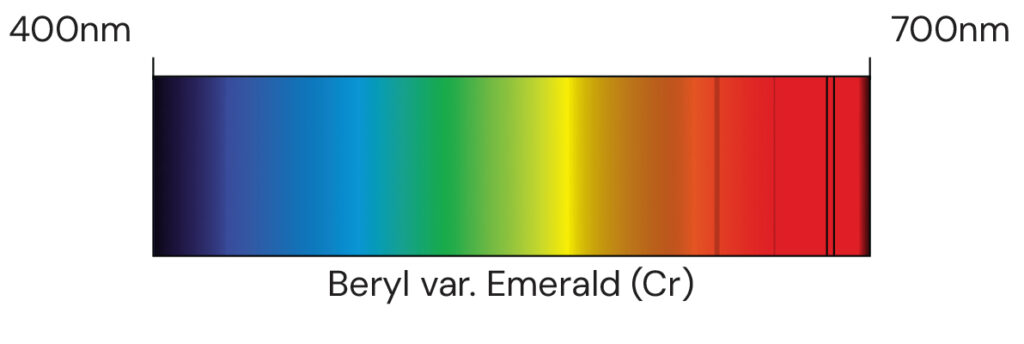

UV-Vis-NIR (Ultraviolet-Visible-Near Infra-Red) spectrometers scan the wavelength range from short-wave ultraviolet to one or a few thousand nanometres. An absorption at 415 nm, caused by nitrogen aggregates, would prove a diamond to be natural, whereas those at 484 and 884, related to nickel, and at 737nm, for silicon, are more likely to be seen in synthetic diamonds. The instrument may help in finding the sources of sapphires and emeralds by separating the former into those which came from igneous or sedimentary rocks, and the latter by the proportions of chromium and iron, which vary between different localities. Valuable Paraiba tourmalines may be distinguished by peaks for copper, from less costly, but similar-looking stones which do not contain that element.

X-ray Diffractometers in Gemmology

X-rays are diffracted by atomic structures just as light waves are by regular structures, such as those of precious opal. X-ray diffractometers are used to measure distances between layers of atoms. Given that the atoms of different elements have different sizes, and, in different materials, they have different arrangements, this information is a sensitive identifying test for mineral species. Even those of polycrystalline aggregates, including rocks, may be separated, and the different mineral species identified. The atomic structures and symmetry of single crystals may be investigated, and this is a routine procedure when new minerals are being studied. It is well known that the method was used to describe taaffeite, the mineral first found as a fashioned stone after attracting the attention of a Dublin gemmologist.

X-rays and other types of radiation may be strong enough to detach electrons from the inner shells of atoms. When this happens, an electron from an outer shell falls in to take its place and, at the same time, emits an X-ray photon of an energy which is typical of a particular element. A detector records these emissions and can give a partial chemical analysis for a material. This may be used to identify stones and coatings and help to separate natural from synthetic stones by detecting the presence of, for example, nickel or silicon in diamonds, which are more typical of synthetic than natural stones. Trace element proportions of chromium, vanadium and iron may help to distinguish between natural and synthetic ruby.

What is a Raman Spectrometer?

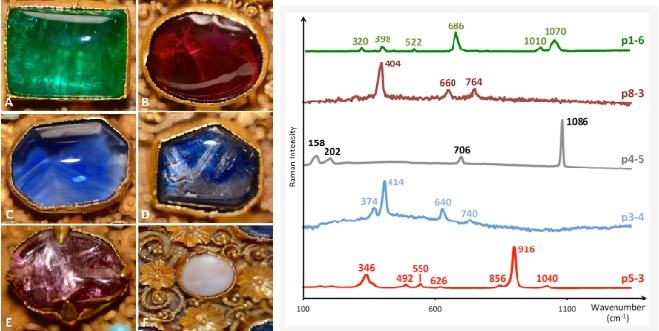

In a Raman spectrometer, a narrow laser beam of infrared or visible light is directed at a material. Most of it is scattered at the same wavelength, but a small amount is at a different wavelength. This difference is displayed on a screen or chart as a diagnostic series of peaks, which can be referred to as a database to identify the material, though it is not usually possible to distinguish between natural and synthetic stones. Sophisticated instruments can be used to identify inclusions, which do not have to reach, though they should be near the surface of a stone.

The lasers used in Raman spectrometers may excite luminescence, the intensity of which can be measured for different wavelengths. The technique is most useful for diamonds because results are improved at low temperatures, after cooling stones with liquid nitrogen. Diamonds may be expected to withstand this process, but other gem species may be harmed by it. Defects in diamonds can be detected at very low concentrations and can provide evidence of natural or synthetic origin and treatment, such as high-pressure, high-temperature colour treatment, which may be hard to confirm by other methods.

Spectroscopy for Professional Gemmologists

The above methods are non-destructive, requiring no special sample preparation, but some advanced instruments detach small amounts of material from the surfaces of gemstones, forming a shallow pit whose diameter is about the same as the width of a human hair. This may be justified by the value premium placed on natural stones and fine stones from certain localities. Material vapourised from the surface of the gem is analysed by a spectrometer so that elemental and isotopic analyses can be studied. Careful comparison with databases may give evidence of the origin (geographical locality) of a gemstone.

Methods of gemstone synthesis and treatment are becoming increasingly sophisticated, and corresponding improvements in instruments, for both laboratories and offices, are needed to cope with them. Spectroscopy has been useful to gemmologists for more than a hundred years, and it promises to develop further to keep pace with the new problems which gemmologists will need to solve.

Main image: Absorption spectrum Beryl var. Emerald

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

If you would like to learn more about Gemmology, you can sign up for our mini online course GemIntro , or explore our accredited programmes