Getting to grips with The Journal of Gemmology Volume 36, No.3, Guy Lalous ACAM EG offers us an edited breakdown of a feature on Bumble Bee Stone from West Java, Indonesia.

Bumble Bee Stone (BBS) is an attractive bright yellow-to-orange and black patterned gem from West Java, Indonesia. Production has been ongoing since 2003, yielding an estimated 150 tons of lapidary material.

The paper in The Journal of Gemmology reports on the location, geology and gemmological properties of BBS, focusing on the cause of its extraordinary colouration.

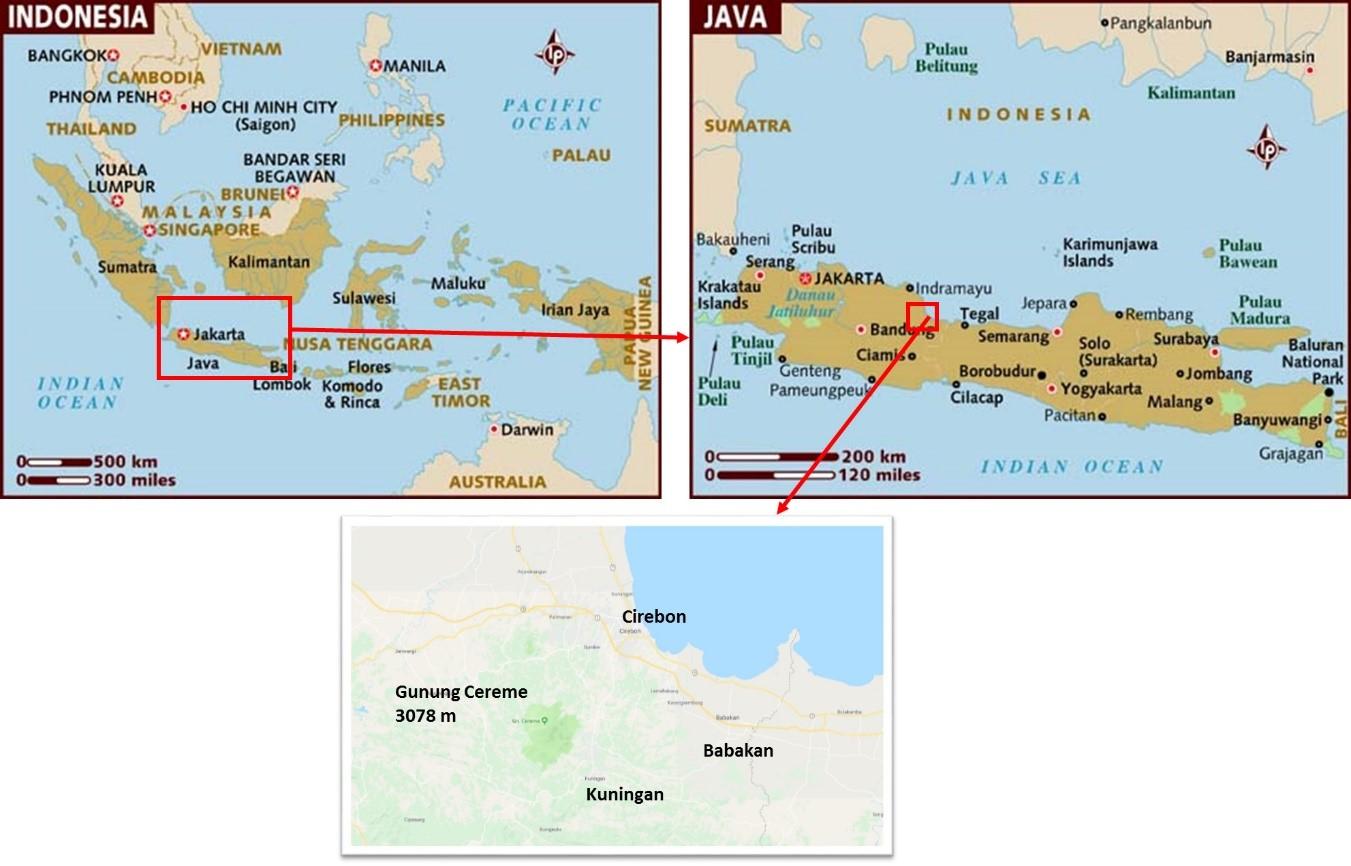

The mining area for BBS is situated on the lower slopes of an active volcano, Mt Ciremai (or Cereme), which is located about 25 km south-west of the coastal town of Cirebon in West Java.

What is a solfatara?

A solfatara is a volcanic area producing hot vapour and sulfurous gases. The name is derived from the Solfatara of Pozzuoli a volcano part of the Campi Flegrei (Burning Fields) near Naples.

BBS was formed within a solfatara (a fumarole that vents gases rich in sulphur) occurring in close proximity to the Mt Ciremai volcano.

This type of vent is common near active stratovolcanoes, and results from the heating of circulating groundwaters containing various elements or compounds extracted from the volcanic system—in this case iron, sulphur, calcium carbonate and arsenic.

Figure 2. The BBS deposit is located at the base of Mt. Ciremai, an active volcano, in the vicinity of Kuningan, West Java, Indonesia.

Figure 2. The BBS deposit is located at the base of Mt. Ciremai, an active volcano, in the vicinity of Kuningan, West Java, Indonesia.

Such a system produces abundant ‘sooty’ pyrite, consisting of very small crystals of the iron sulphide, crystallising rapidly near the surface, which looks like black soot.

As the gases escape the solfatara, minerals are deposited as more-or-less regular bands in fractures within the volcanic rock, which is here comprised of fine-bedded volcanic ash and intercalated pyroclastic tuff (an accumulation of volcanic ejecta of varied size).

The veins are near vertical, with individual colour bands rarely exceeding 5 cm. The tuffaceous wall rock contains marcasite, an iron sulphide that is unstable when exposed to air and moisture.

After about 1–2 weeks in this environment, the breakdown of marcasite facilitates the separation of BBS vein material from its volcanic host rock.

Figure 3. The pulverulent appearance of the colour banding in BBS is shown here under magnification in sample no. 1591.

Top: Yellow-to-orange pigment is disseminated within the carbonate matrix, forming colour bands, within with micro-geodes are found.

Bottom: The black pigment forms minute discs that are resolvable only at higher magnification. Photomicrographs by E. Fritsch.

The gemmological properties of the material are reported. Refractive index values were difficult to measure because of the material’s porosity.

Specific gravity varied between 2.42 and 2.74; the average of seven measurements was 2.57. Bubbles appeared when a drop of diluted hydrochloric acid was placed on the surface, confirming that this material is carbonate rich.

Therefore, it is not jasper, which is an opaque form of microcrystalline quartz. When examined with the binocular microscope, the appearance was that of coloured powders cemented in the carbonate matrix.

Small cavities were actually micro-geodes; many contained very small crystals that were orange or tended towards red. Visible-range reflectance spectra for the various coloured areas of BBS revealed that the yellow regions have an absorption edge at ~530 nm, the colour perceived is a combination of all wavelengths above 530 nm (green), which is observed as yellow.

The absorption edge shifted towards 550 nm in the orange areas which is logical as less yellow equates to more red. The black portions showed a nearly flat spectrum.

What about pararealgar?

Pararealgar is a bright yellow monoclinic polymorph of realgar, a more common and better-known red arsenic sulphide, which is also monoclinic but with a different class of symmetry.

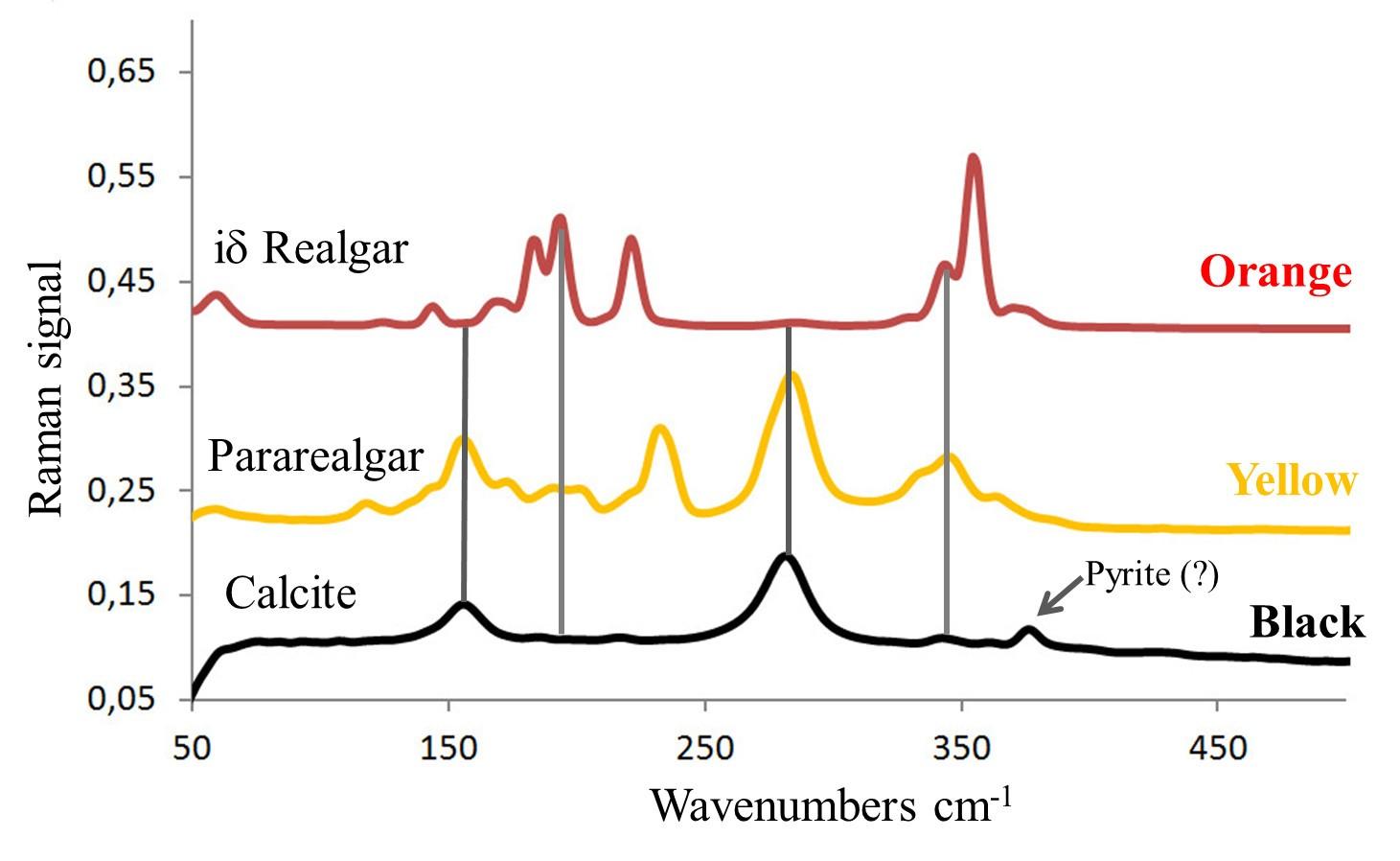

The Raman spectra of all analysed samples presented bands for calcite at about 285 and 160 cm–1. Aragonite bands were found in only one part of one orange sample. In ‘mustard’-to-yellow parts, additional major bands were recorded at about 346, 284, 233 and 157 cm–1.

They correspond to pararealgar, which has the formula As4S4. The Raman spectrum of realgar dominated the bright orange areas and the reddish crystals in the micro-geodes mentioned above, with main peaks at approximately 355, 221, 194 and 184 cm–1.

It had a much higher Raman scattering intensity than pararealgar, thus it dominated the spectrum of a mixture of both polymorphs.

As such, the orange areas appeared to be a mixture of pararealgar and realgar. In the black areas, a small Raman signal appeared at about 378 cm–1. The closest signal we could find is pyrite, FeS2, which has a strong doublet at 385 and 355 cm–1.

Figure 5. The Raman spectra of the BBS samples tested always showed peaks for calcite, with additional features corresponding to pararealgar and realgar in yellow and orange areas. The spectrum shown here for realgar is from a reference crystal, as no area of BBS we analysed consisted of pure realgar.

What about framboidal pyrite?

The term framboid describes an aggregation of uniformly-sized particles of the same mineral, from the French framboise for raspberry, as this berry is composed of aggregated uniformly sized drupelets.

Figure 6. The three polished specimens of BBS on the left (12–26 cm long) show spectacular orbicular (also called ‘bull’s-eye’) patterns with a strong colour contrast. The typical bull’s-eye pattern ranges from 10 to 14 mm in diameter, but may be much larger (see Figure DD-1 in The Journal’s online Data Depository). Such pieces are derived by cutting across botryoidal areas such as shown by the BBS slab on the right. The colourless calcite crystals (up to ~3 cm long) induce the botryoidal structure in the overlying sulphide-bearing layers. Photos by J. Ivey.

Scanning Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis were performed on the material.

The nearly ubiquitous presence of Ca confirmed that the material is mostly calcite, although the consistent presence of a small Mg peak suggested it was a slightly magnesian calcite.

Yellow-to-orange areas were rich in S and As. The black discs were composed of circular aggregates with maximum diameters ranging from ~5 to 30 μm.

They were composed of micrometer-sized crystals identified as pyrite. Their morphology varied, from nearly cubic (square faces) to cubo-octahedral (pseudo-hexagonal faces) to octahedral triangular faces. This is reminiscent of framboidal pyrite.

What about botryoidal concretions?

A concretion is a compact mass of a mineral formed by precipitation within the spaces between sediment layers. Botryoidal refers to the crystal shape resembling a bunch of grapes.

BBS belongs to a rare category of gems coloured by micro-inclusions of sulphide pigments.

Its most remarkable characteristic is a bright yellow colour, which is caused by the presence of an unexpected sulfide, pararealgar. The orange colour in some samples consists of a mixture of pararealgar and realgar. Both minerals are polymorphs of As4S4, arsenic sulphide.

This is not the first time that pararealgar has been identified as the colouring agent in a gem material. Gaillou (2006) documented this pigment via Raman scattering in a little-known bright yellow opal from the area of Saint Nectaire in central France.

BBS is currently a single-source gem material, with no other deposit having been documented elsewhere.

The most sought after is an orbicular variety with a typical bull’s-eye pattern, obtained by slicing across botryoidal concretions.

This is a summary of an article that originally appeared in The Journal of Gemmology entitled ‘Bumble Bee Stone: A Bright Yellow-to-Orange and Black Patterned Gem from West Java, Indonesia’ Emmanuel Fritsch and Joel Ivey 2018/Volume 36/ No. 3 pp. 228-238

Cover Image: These cabochons (up to 40 mm long) and rough pieces of Bumble Bee Stone (BBS) were produced in 2017, the samples are more orange than previously mined material.

Photo by J. Ivey.

Interested in finding out more about gemmology? Sign-up to one of Gem-A’s courses or workshops.

If you would like to subscribe to Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology please visit Membership.

{module Blog Articles Widget}