The beryl family of gemstones is fantastically versatile as it includes gems that come in a veritable rainbow of colours. For those of you who may think that you’ve never even heard of a beryl, think again! Within the beryl group are a slew of well-known gems that are regularly used in jewellery. Gem-A gemmology tutor Lily Faber FGA DGA EG takes us through the variety brilliantly coloured gems belonging to the beryl family.

A beryl by any other name would be: emerald (green), aquamarine (blue), morganite (pink), heliodor (yellow), goshenite (colourless), red beryl and pezzottaite (pinkish-red to pink). Each coloured stone comes with its own name, colouring element and sometimes unique physical properties.

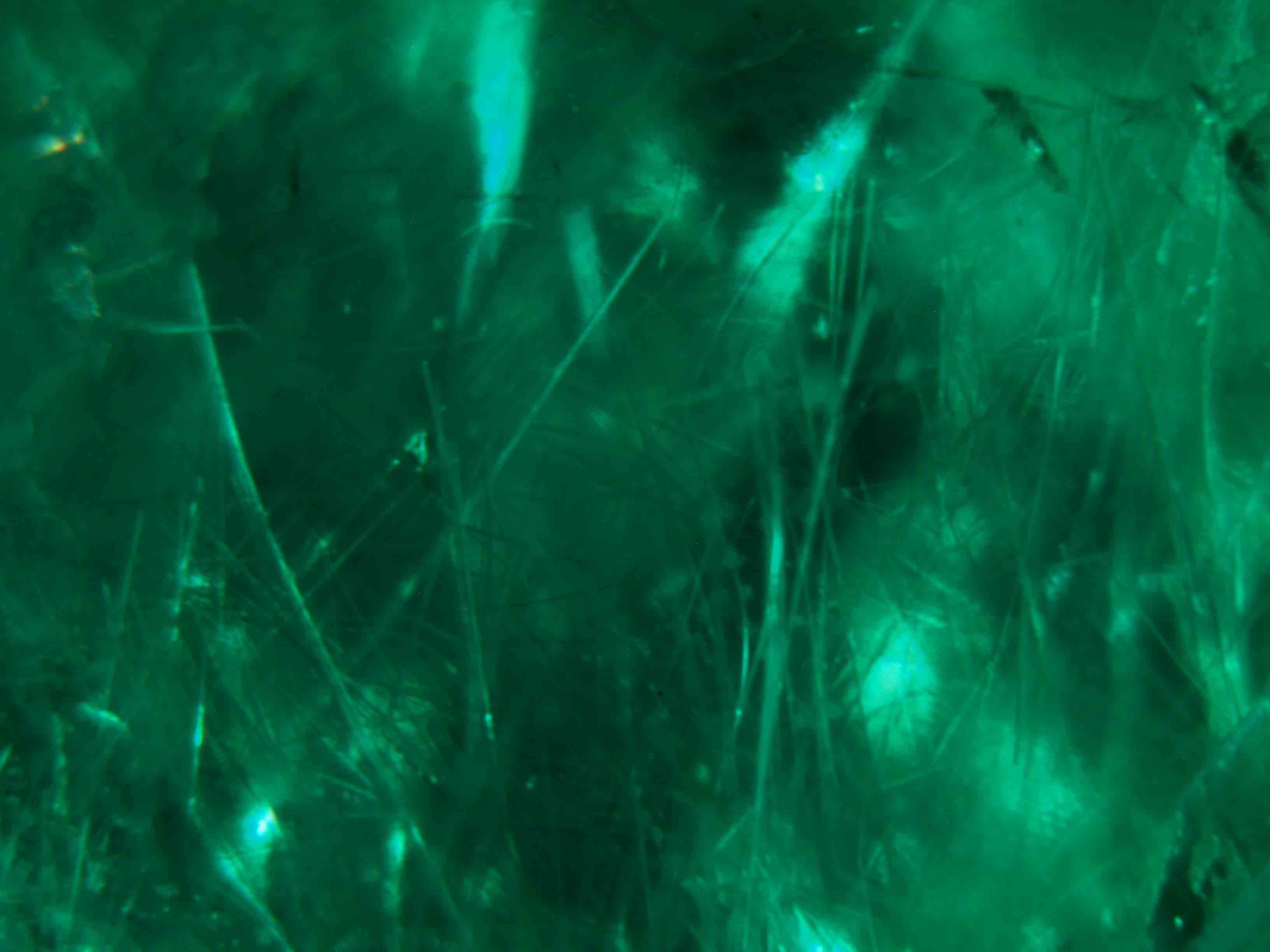

Amphibole fine crystal inclusions present in an emerald. Image credit: Pat Daly FGA

Amphibole fine crystal inclusions present in an emerald. Image credit: Pat Daly FGA

Overall, beryls are fairly hard and can be worn in rings, earrings and necklaces. Caution should be exercised when wearing these gems in rings, however, as beryls can be brittle and chip easily, especially emeralds and red beryls, due to their generally higher quantities of inclusions.

The Beryl Family: Emerald

Emeralds are perhaps the most widely known variety of beryl and are birthstone for the month of May. Their rich green colour, caused by traces of chromium and vanadium, has made them desirable for centuries. Colombian emeralds are amongst the most sought after and expensive emeralds.

Read more: Exploring the Emeralds of Colombia

Generally, emeralds are included to varying degrees, containing minerals such as pyrite, mica and needle-like amphibole. Colombian emeralds are known for their three-phase inclusions, which are tiny cavities inside the stone containing a solid mineral, a liquid and a gas bubble. Most of the emeralds on the market have at least some internal fractures which are often filled with oil to improve the appearance of clarity.

The stone is also notoriously brittle and the eponymous emerald cut (a rectangular step cut with the corners removed) was created to make it more wearable and to protect the stone from damage.

Read more: What Can Emerald Inclusions Tell Us About Origin?

Another type of emerald is the trapiche, which consists of a central, green, hexagonal crystal surrounded by six wedge-shaped rays separated by a mixture of colourless beryl and black inclusions. The trapiche emerald is increasingly gaining popularity in jewellery settings and is a fun and more affordable alternative to the finest emeralds.

The Beryl Family: Aquamarine

Literally translating to ‘sea water’, aquamarine is coloured by iron and occurs naturally as a pale, bluish-green colour. In the 19thcentury, blue-green aquamarines were preferred but now, stones are usually heat treated to remove the green hue, thus producing a purer blue colour. The more intense the blue colour, the higher the value. These stones tend to be clean but may contain an inclusion called ‘rain’, which consists of long, thin gas or liquid-filled tubes that run parallel to one another. ‘Rain’, if it is abundant enough, can cause a cats-eye effect which can be a lovely addition to your stone if you enjoy inclusions.

The Beryl Family: Heliodor and Golden Beryl

Both heliodor and golden beryl are yellow in colour, but the former often has a hint of green while the latter is a saturated yellow to orangey-yellow. As they are both yellow beryls, the names are sometimes interchangeable in the trade. Heliodor and golden beryl are very clean gems with few inclusions and, like aquamarine, are coloured by iron.

The Beryl Family: Morganite

Named after the nineteenth-century banker and gemstone enthusiast J.P. Morgan, morganite is the pink to orangey-pink member of the beryl family coloured by manganese. It has enjoyed enhanced popularity in the trade in recent years due to the high prices being paid for pink diamonds such as the ‘Sweet Josephine’, a 16.08 carat pink diamond that sold for $28.5 million at Christie’s Geneva in 2015.

Rough and cut morganite. Image: Gem-A

Rough and cut morganite. Image: Gem-A

The Beryl Family: Goshenite

Goshenite is a beryl in its purest form without any colouring agent mixed into the crystal structure during growth. It was named after Goshen, Massachusetts in the USA where it was first discovered. Historically, due to its clarity, beryl has been used for lenses and eyeglasses. It is occasionally used as a diamond simulant, however it does not possess the same fire or level of brilliance.

The Beryl Family: Red Beryl

Red beryl is a rare variety of beryl and is a deep red colour. It may also be called bixbite in some areas of the trade, however, CIBJO regulations have ruled out the use of the term ‘bixbite’ as it is too close in name to another mineral, bixbyite, which is completely different. It is so rare that it is more of a collector’s stone than one used in jewellery.

Read more: Understanding Rare Red Beryl

Examples of pear-cut red beryl. Image: Henry Mesa, Gem-A

Examples of pear-cut red beryl. Image: Henry Mesa, Gem-A

The Beryl Family: Pezzottaite

Discovered in 2003 and named after gemmologist Federico Pezzotta, pezzottaite is a rare pinkish-red to pink gemstone. Initially, it was believed to be a red beryl, but it has since been discovered that the chemical, optical and physical properties separate this gemstone from the varieties mentioned above. It does not often appear in jewellery due to its rarity and several of the mines where it has been unearthed are now exhausted.

A cut and faceted pezzottaite specimen. Image: Henry Mesa, Gem-A

Interested in expanding your gemmological knowledge? You might like to consider taking one of our Short Courses or Workshops.

Find out more about the Gem-A Gemmology Foundation course and the Gem-A Gemmology Diploma here.

Cover image: A rough emerald. Image: Henry Mesa, Gem-A