Gemstone inclusions are a fascinating area of study for gemmologists

But they can also be helpful in determining the identity of a stone and, in some cases, may be indicative of its origin. You may instantly recognise some inclusions if you have completed the Gem-A Gemmology Foundation or Gem-A Gemmology Diploma. Here, Tutor Pat Daly explores some of the most instantly recognisable internal features of gemstones.

The term inclusion refers to any feature seen in a gemstone. It includes solids, liquids and gases, colour distribution, fractures and cleavages and structures related to the formation of the material. Gemstones may be crystals, polycrystalline masses, rocks, materials produced by the activities of living organisms, or by the collision of extra-terrestrial materials with Earth. The internal features of each of these types depend partly on how they were formed and may give clues to the processes involved. Inclusions in diamonds, for example, provide insights into Earth’s mantle and the deeper parts of the crust and supply evidence of the rocks in which they formed and the conditions in which they grew. This information is welcome because these areas of our planet are inaccessible, and diamond is one of the few materials which encapsulate and protect it from alteration.

Gemstone Inclusions as Identifying Features

Inclusions can help gemmologists to decide the identity and source of a gemstone and whether it has been treated in any way. Artificial materials such as synthetic stones are recognised chiefly by their inclusions. Often, it is not a simple matter to make these decisions, and other methods, which may not be accessible to gemmologists outside laboratories, may be needed to confirm them.

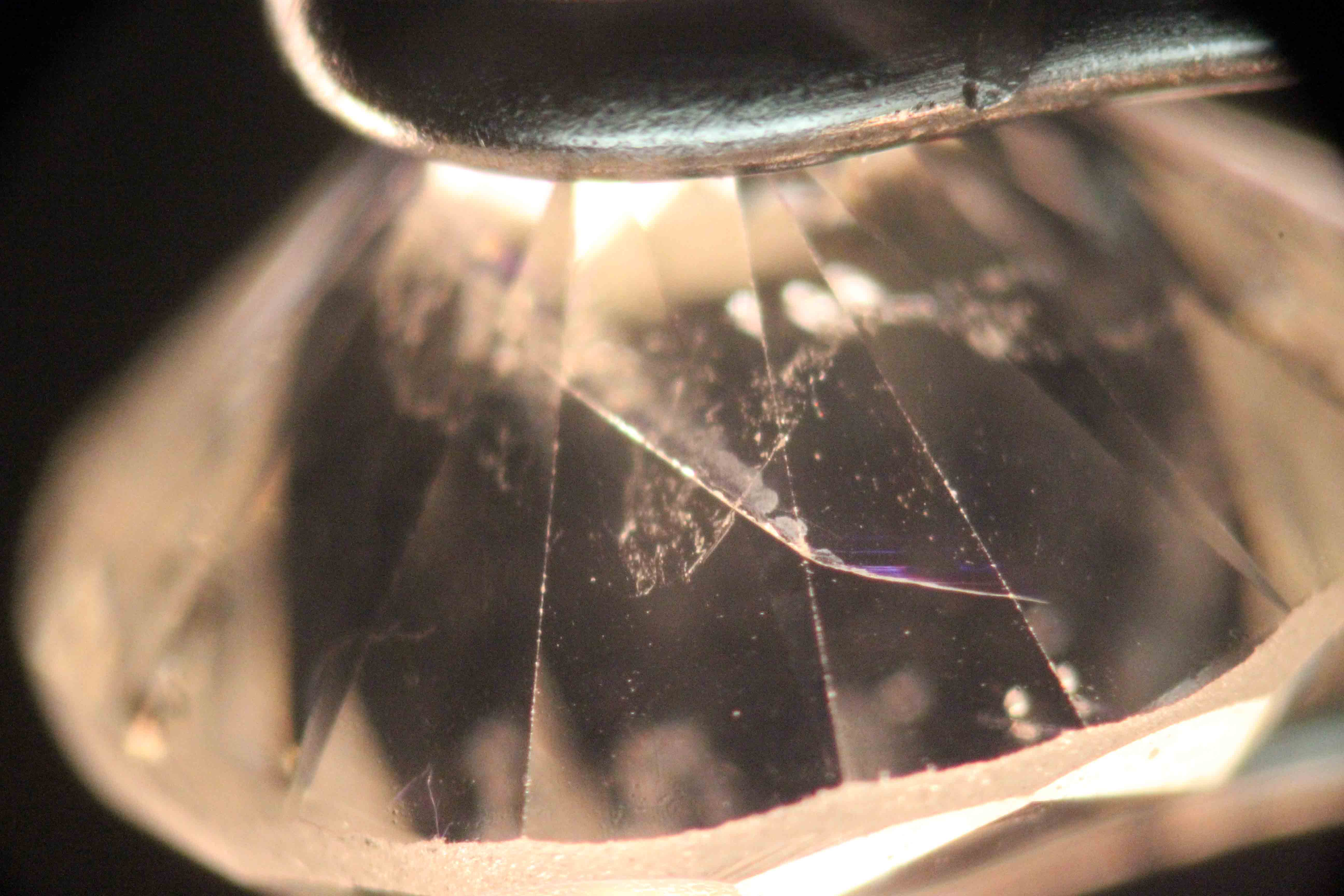

Fracture filled diamond from the Gem-A Archives.

One way of classifying inclusions is by their time of formation relative to their host. Some formed before the growth of the stone in which they are found, others at the same time and some after the host gemstone had stopped growing. The first two groups are beneficial for recognising gem species and their sources and whether they are natural or artificial materials. Inclusions which postdate or have been changed after the growth of their host can be used to recognise treatments, such as heat treatment, fracture filling and artificial colouration.

Crystal and Fluid Gemstone Inclusions

They may also be divided into crystals and fluid inclusions. Crystals can form either before or at the same time as the stone in which they are seen but fluid inclusions, excluding air-filled fractures and cleavages, form during growth. Many are irregularly shaped, but some have the shapes of crystals and are called negative crystals. These may sound unlikely, but they are common.

Negative crystal inclusions in corundum photographed by Pat Daly.

Fluid inclusions may contain liquid, gas or both and may also enclose crystals. Two-phase inclusions enclose two of them, and three-phase inclusions all three. The term monophase may be used for those containing only liquid or gas, but it is used less often.

Fluid inclusions may be arranged in feathers. Feathers are planar or curved planar features in gemstones and artificial materials. Those composed of fluid inclusions are thought to form when stones break during growth, and fluids which contain their chemical ingredients are drawn into the cracks, partially repairing them.

Gemstone Inclusions and Visual Appearance

Some inclusions add to the visual appeal of gemstones. For example, abundant, oriented needle-like crystals are responsible for star and cat’s-eye effects in some cabochon-cut stones. Aventurescence, a spangled or sparkling effect, depends on parallel platy crystals which act as tiny mirrors in some quartz gems and sunstone feldspars.

Cat’s eye chrysoberyl photographed by Pat Daly.

Crystal inclusions are sometimes valued in their own right. Quartz crystals, for example, form in many geological environments and may enclose any mineral which can coexist with it (peridot, and some others, cannot). This means that interesting collections can be made of many minerals, some of which are colourful and well-formed. Minerals which are not durable enough to be suitable for use as gemstones can form desirable varieties when they are enclosed and protected by quartz. Examples include chrysocolla, a sky-blue mineral which usually discolours when exposed to air but retains its beautiful appearance when included in quartz, and rutile, golden needles that are easily broken except when they occur as inclusions.

The Top 5 Most Recognisable Gemstone Inclusions

Of all the inclusions found in gemstones, a few may be mentioned as being particularly well-known and representative of the different types. Many inclusions might compete for the list, but the following five have been chosen.

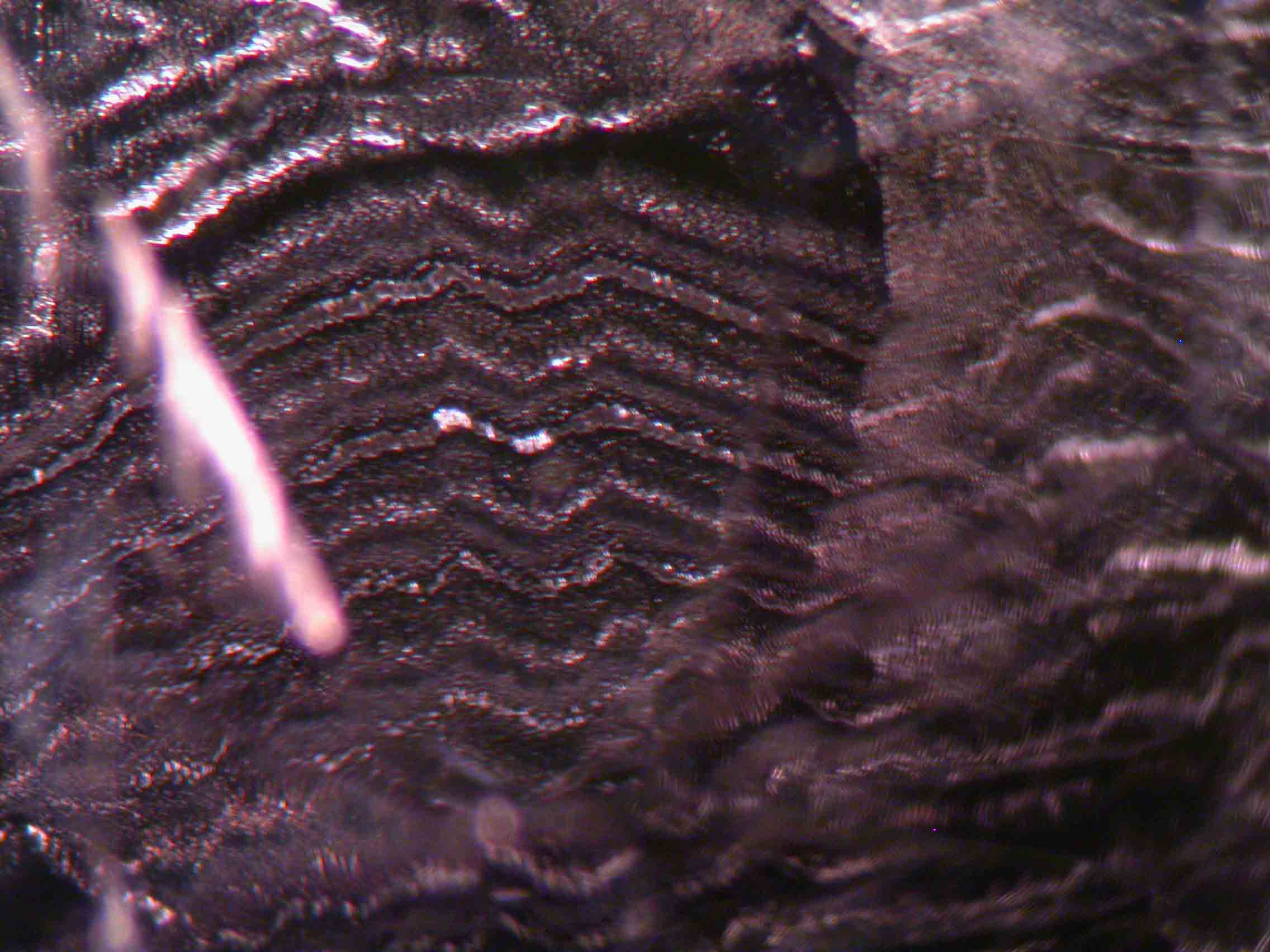

Tiger Stripe Inclusions

Tiger stripe, also known as zebra stripe, is a type of feather found in amethyst. It is distinctive, unsurprisingly, because it is marked by wavy stripes. The inclusion is related to twinning in the crystal, is sometimes iridescent and may consist of three distinct sectors reflecting the mineral’s trigonal symmetry.

Tiger stripe inclusions in amethyst photographed by Pat Daly.

Tiger stripe in a purple stone may be regarded as proof that it is amethyst. It may also be seen in some citrines produced by heat-treating amethyst. It is taken as evidence of natural origin, though there are reports that it may be induced in synthetic stones.

Horsetail Inclusions

When complete, horsetail inclusions in demantoid garnet consist of a dark crystal of chromite (chrome and iron oxide) surrounded by a spray of radiating, golden-coloured fibres, which may be asbestiform serpentine or channels in the stone. Demantoid has a RI above the limit of the standard refractometer, so these inclusions, or some part of them, afford welcome confirmation of identity. The best-known source for demantoid is Russia, but there are other sources. Horsetail inclusions occur in stones from some of them, not from others.

Horsetail inclusion in demantoid garnet photographed by Pat Daly.

Animals and Plants Preserved in Amber

Amber is a gem material famous for the animals and plant remains it preserves as fossils. These are of general interest to gemmologists and jewellers, but they represent a treasure trove to palaeontologists trying to understand ancient environments. Fossils include flies, which may be very well preserved, showing details of the wings and limbs of the animals. Spiders, mites and other small creatures are relatively common, and rare vertebrate fossils are found.

A fly trapped in amber photographed by Pat Daly.

However, any buyer of an expensive piece containing one is well-advised to obtain an independent opinion of its authenticity. The most exotic remains are those thought to have belonged to small dinosaurs.

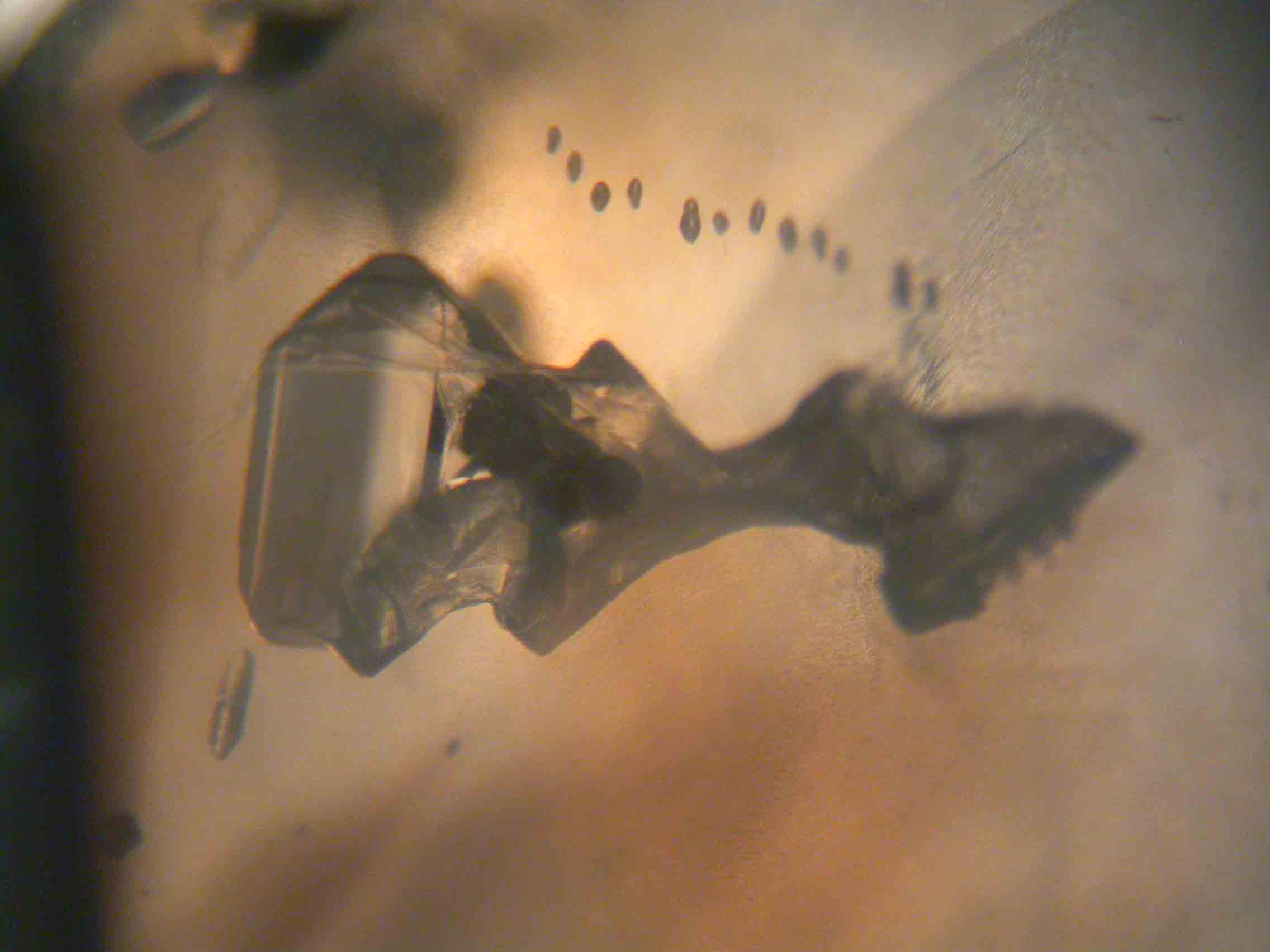

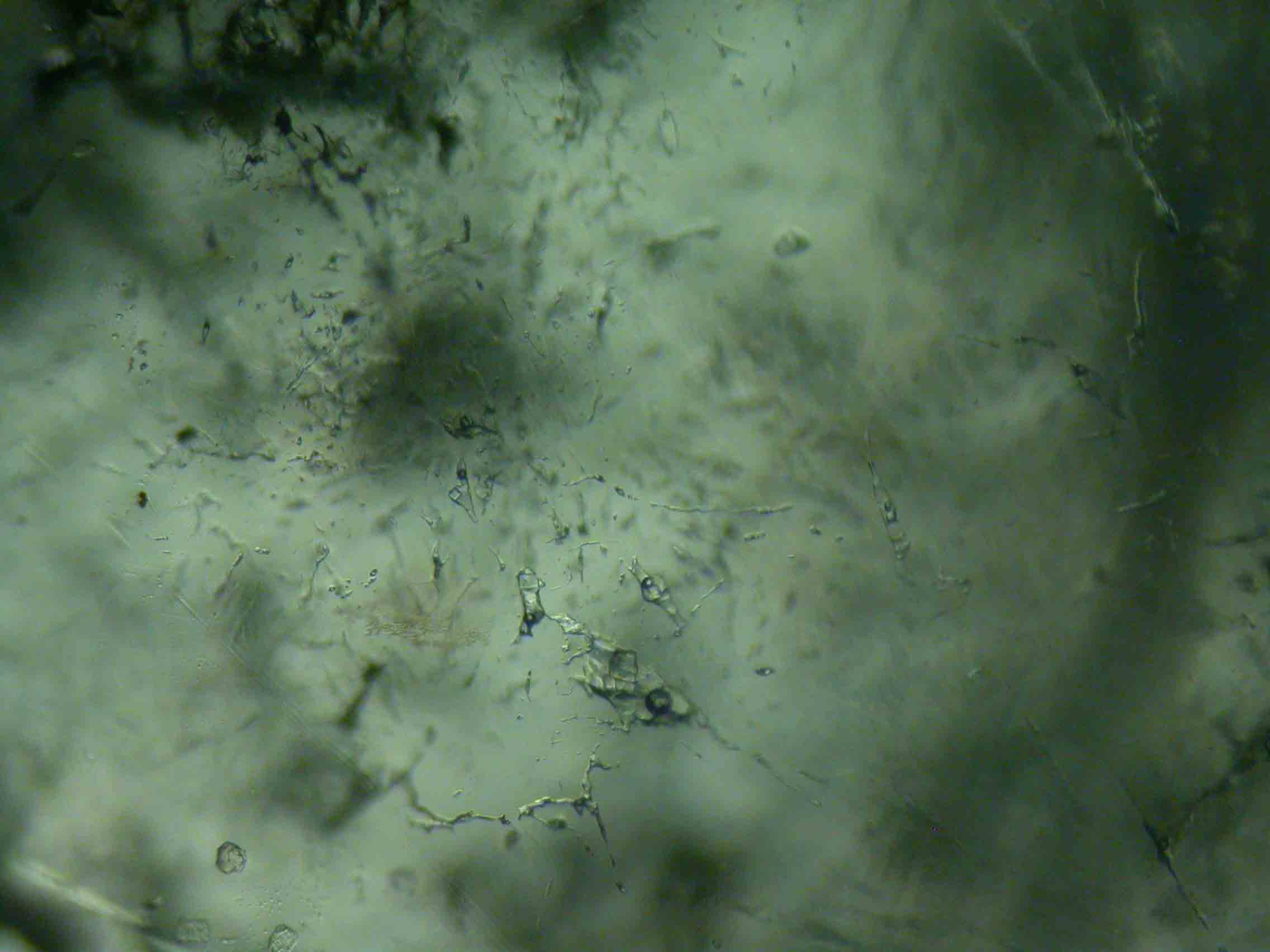

Three-Phase Inclusions in Colombian Emerald

Gemmology students soon become acquainted with the three-phase inclusions found in Colombian emeralds. These consist of a bubble in brine, accompanied by a square or oblong-looking crystal of salt enclosed in a spiky cavity. The crystals are cubes but often appear two-dimensional because the cavities are so thin. Three-phase inclusions are not confined to emeralds from Colombia or to emeralds; they have been seen in stones of other gem species and even, on occasion, in synthetic emeralds. Nonetheless, experienced laboratory gemmologists can use these inclusions to identify emeralds as natural and, by close study, assist them in stating the likely source of a stone.

Three phase inclusions in emerald photographed by Pat Daly.

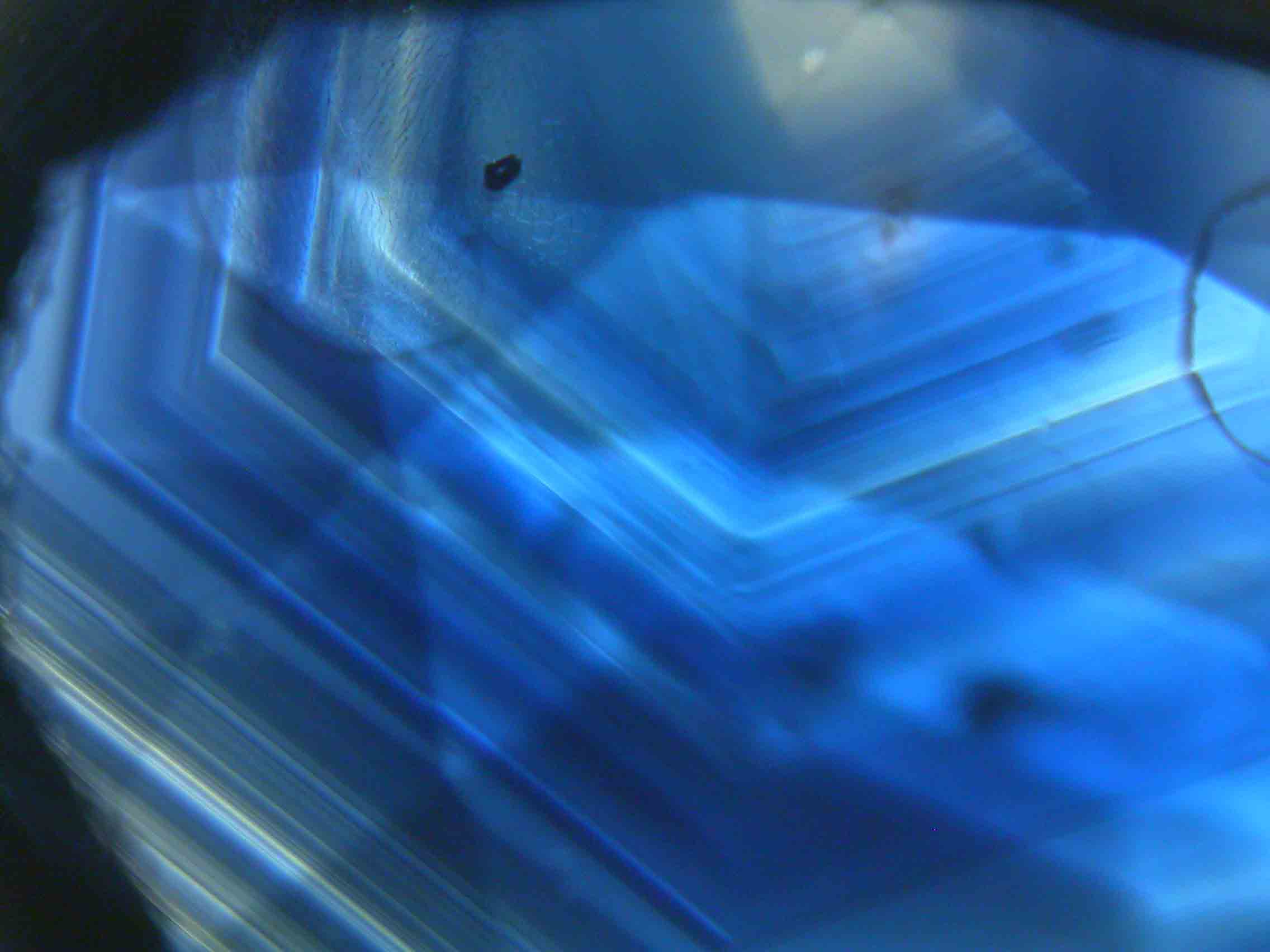

Colour Zoning in Gemstones

Colour zoning may seem commonplace in gemstones, but it can reveal much about their identity and history. Straight colour zoning is a well-known feature of natural blue sapphires and the citrine variety of quartz, for example. It is more helpful when it is appreciated that, although possible in any species, it is uncommon in yellow and blue stones other than these.

Main image: tiger stripe in amethyst photographed by Pat Daly.

Angular colour zoning in sapphire photographed by Pat Daly.

Kyanite and some rare blue euclase display it, but they are exceptions which are easily identified by other means. Flux-grown synthetic sapphires show straight colour zoning, so the feature does not guarantee that a stone is natural, though most synthetic sapphires are made by the Verneuil process and display curved colour zoning. The pattern of colour concentration may also reveal the colour treatment of sapphires and other gems.

Conclusion

Inclusions can either enhance a gemstone’s uniqueness and scientific interest or detract from its clarity and durability, influencing its overall value. Inclusions in gemstones are useful because they provide gemmologists with ways in which gemstones may be identified, and artificial stones and treatments may be recognised. Those who study gemmology also come to see that inclusions are fascinating, often beautiful features which add greatly to the pleasures of studying the materials with which they deal in their everyday work.