Are you fascinated by the beautiful colours of opal? Do you wish you knew more? Here, Gem-A assistant gemmology tutor, Charlie Bexfield FGA DGA EG offers a beginner’s guide to opal types, including common and precious varieties.

Types of Opal

Opal is comprised of tiny silica spheres, formed when silica-rich water seeps into deep cracks and voids in the Earth’s crust.

It is separated into two groups, common opal (also known as potch) and precious opal (also known as noble opal). Opal can be found all over the world from Cornwall to Canada, Australia to Siberia, Ethiopia, Madagascar and many other locations.

A cross section of opal in its host rock. Photograph by Henry Mesa.

What is the difference between precious and non-precious opal?

Precious opal shows a play of spectral colours though the stone whereas common opal does not. Common opal is usually opaque to translucent and brownish orange in colour, however it can come in any colour, some of which are quite attractive.

Key Varieties of Common Opal

Agate Opal

The banded variety of common opal which can form in opalised fossils or in veins.

Dendritic or Moss Opal

These moss like (dendritic) inclusions are formed of different iron minerals encased by the opal producing these aesthetic designs. Other names include ‘landscape’ opal in which the branch like structures of the iron minerals resemble that of a woodland landscape.

Common green opal with dendritic inclusions, also known as moss opal. Photograph by Henry Mesa.

Some of the more sought after common opal comes from Peru. Very pretty blues, pinks and bluish greens can be found there. These come from the two main provinces: Ica and Caraveli. The best blues come from Caraveli and are known as Andean opal. Ica produces the better pinks, but both mines produce both colours.

Read more: Questions to Ask When Buying Gemstone Jewellery

There are many more varieties of common opal but two other important varieties are fire opal – this is the intense orange colour opal – and hyalite, the translucent variety of opal that doesn’t display a play of colour.

Understanding Precious Opal

This variety of opal displays play-of-colour. Diffraction of light through very small apertures between silica spheres within the structure creates these flashes of colour. This cannot be confused with the reflections caused by foils within simulant opals, as play-of-colour is prismatic or rainbow-like.

Read more: How to Assess the Value of an Opal

Basil Anderson sums up the identification of precious opal quite wonderfully with this quote, included in The Opal Book by Frank Leechman: “As regards to identification, there is little that need be said concerning opal, since, except in the variety of fire opal, it is a stone that cannot effectively be imitated, as soon as prismatic colours are seen.”

A cushion-cut fire opal. Photograph by Henry Mesa.

This quote still stands today. Red, orange and yellow are the most desired spectral colour to be seen in opal and therefore command higher prices. Blue and green are less desirable colours, although still beautiful.

White Opal

This is the most ubiquitous variety of opal. It has a white background and is sub-transparent to translucent and usually displays opalescence. The best examples will show all the spectral colours. It is now considered to be less valuable than black opal.

However fine white opal still commands high prices and is very attractive. Most white opal comes from Marla, Australia and Whitecliffs, Australia, but is also found in Hungary, Ethiopia and Canada.

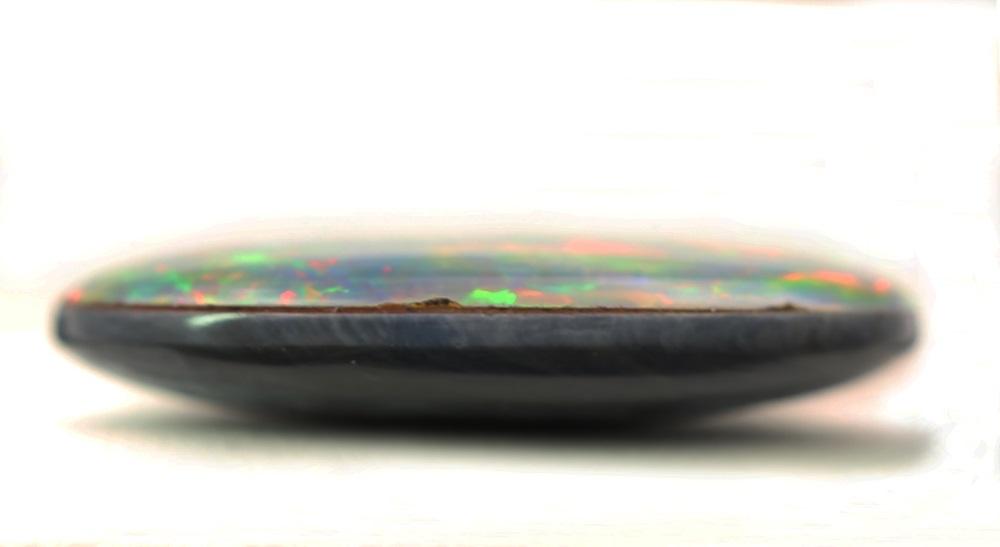

Black Opal

Displaying a black body colour with little to no opalescence, this variety is now the most desirable. The black background allows the yellows, oranges and reds to ‘pop’ in contrast to the dark background, supposedly making the play of colour more impressive.

An opal cabochon with flashes of orage, red and green. Photograph by Henry Mesa.

Once again the intensity and fullness of the play-of-colour contributes to the pricing. Black opal predominantly comes from Lightning Ridge, Australia, but can also be found Hungary, Honduras and the USA.

Boulder and Matrix Opal

These varieties occur when opal forms in narrower veins and is cut and polished within the host rock. Boulder opal was first discovered in Queensland, Australia, it can also be found in Brazil and Canada.

Read more: Top 10 Luxury Jewellery Brands

Boulder opal veins are larger than matrix opal veins which form as a fine network within the host rock. Matrix opal is found near Yowah in Queensland, Australia.

Water Opal

This is the colourless variety of precious opal and can have a soft appearance. Usually the play-of-colour appears to be inside the stone against a colourless transparent background, which means it can appear minimal. The best examples are from Mexico, other localities include Australia and the USA.

What about Composites?

Doublet

Comprised of two parts glued together, the top is a slice of opal on a dark opaque backing made of plastic or another gem material. In the more convincing examples ironstone is used in an attempt to mimic the host rock of boulder opal.

An opal doublet, pictured to highlight the seam between the slice of opal and its dark opaque backing.

Photograph by Henry Mesa.

Triplet

Very similar to the doublet, but the slice of opal is much thinner and crowned by a transparent colourless domed cabochon made of quartz, plastic or glass. This does two things, it protects the opal and also works as a magnifier for the play of colour. Viewed from the side, the colourless material can easily be spotted. Once again it is mounted on a dark opaque background to give the appearance of black opal.

Read more: Understanding the Value of Sapphires

Other composites, simulants and treatments exist and can be more convincing. If you would like to know more, please contact Gem-A on education@gem-a.com to enquire about our courses. ■

Learn more about gemstones with the Gem-A Gemmology Foundation course, here.

If you’re not ready to embark on a course with Gem-A, why not try our workshops? Discover more, here.

Cover image: An oval-shaped blue opal triplet photographed by Henry Mesa.