Guy Lalous ACAM EG is on-hand to summarise some of the more in-depth articles from Gem-A’s The Journal of Gemmology. Here, he delves into a feature on Mexican amber and the use of FTIR spectroscopy to determine provenance from the Winter 2017 issue.

Amber is an organic gem. Organic gems are the products of living, or once-living, organisms and biological processes. Amber derives from fossilised resins produced by prehistoric trees.

Such resins are produced by plants in response to certain circumstances, such as defence against insect pests or protection of wounds.The most important resin-producing plant families are classified among the gymnosperms (conifers) and the angiosperms (flowering plants).

The fossilisation process of amber involves a progressive oxidation, where the original organic compounds gains oxygen, and polymerisation, which is an additional reaction where two or more molecules join together. This process produces oxygenated hydrocarbons, which are organic compounds made of oxygen, carbon and hydrogen atoms. A peculiarity of amber is that it may perfectly preserve an organism in its original life position.

What about the Yi Kwan Tsang Collection?

This collection consists of 115 amber samples from Chiapas, many of which contain abundant plant and animal fossil inclusions. The ambers were acquired over a 10-year period (~2004–2013) in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico. The collection was displayed in 2015 at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show and in 2016 at the Beijing International Jewellery Fair.

Figure 1: This necklace from the Yi Kwan Tsang Collection contains amber beads from the San Cristóbal de las Casas area of Chiapas, Mexico, and was made by Francesca Montanelli (Lutezia Jewels, Stradella, Italy). Photo by Francesca Montanelli.

This article characterises Mexican amber from the Yi Kwan Tsang Collection using a variety of methods, including those not very common in gemmology, such as taxonomy studies and mass spectrometry, using techniques optimised for organic molecules. Some of the data was compared to those obtained from amber samples from the Baltic Sea and the Dominican Republic.

The most important amber mines in Mexico are located in the area of Simojovel, but there are several deposits elsewhere in Chiapas State. They date back to the Late Oligocene/Early Miocene (23-13 Ma).

The area is characterised by three stratigraphic units that contain amber. From bottom to top, these are the La Quinta Formation (28–20 Ma), the Mazantic Shale (23–14 Ma) and the Balumtum Sandstone (16–12 Ma). Most of the amber deposits are associated with lignites, friable shales and deltaic clays in the sandstone.

There are hundreds of amber mines in the tropical forest around Simojovel, and the amber is mined manually using hammers and chisels.

The twenty-seven samples examined for inclusions were transparent and typically ranged from golden yellow, orange and orange-red to dark orange; a few pieces were dark brown, and some displayed a little natural green colouration. Internal features consisted of inclusions, as well as less common colour variations and small surface fractures. The fractures are probably related to stress associated with the polymerisation of the resin.

All of the pieces were inert to short-wave UV radiation but displayed weak to strong fluorescence to long-wave UV. The RI values were constant (1.540), and they were similar to those of Baltic and Dominican amber. Average SG values were found to be homogeneous and relatively low (1.03).

What about taxonomic classification, taxa and phylum?

Taxonomic classification is a hierarchical system used for classifying organisms to the species level. A taxa is a group in a biological classification, in which related organisms are classified. Phylum is a taxonomic ranking that comes third in the hierarchy of classification, after domain and kingdom. Organisms in a phylum share a set of characteristics that distinguishes them from organisms in another phylum.

What about arthropods?

The largest phylum of creatures on Earth without a doubt is Arthropoda, both in terms of number of species and in total number of individuals. There are nearly 1 million species of Arthropods, with over 90% of them being insects.

The determination of the taxa of the botanical and animal inclusions was difficult because the species that lived in Chiapas during the Oligocene-Miocene were different from the modern ones.

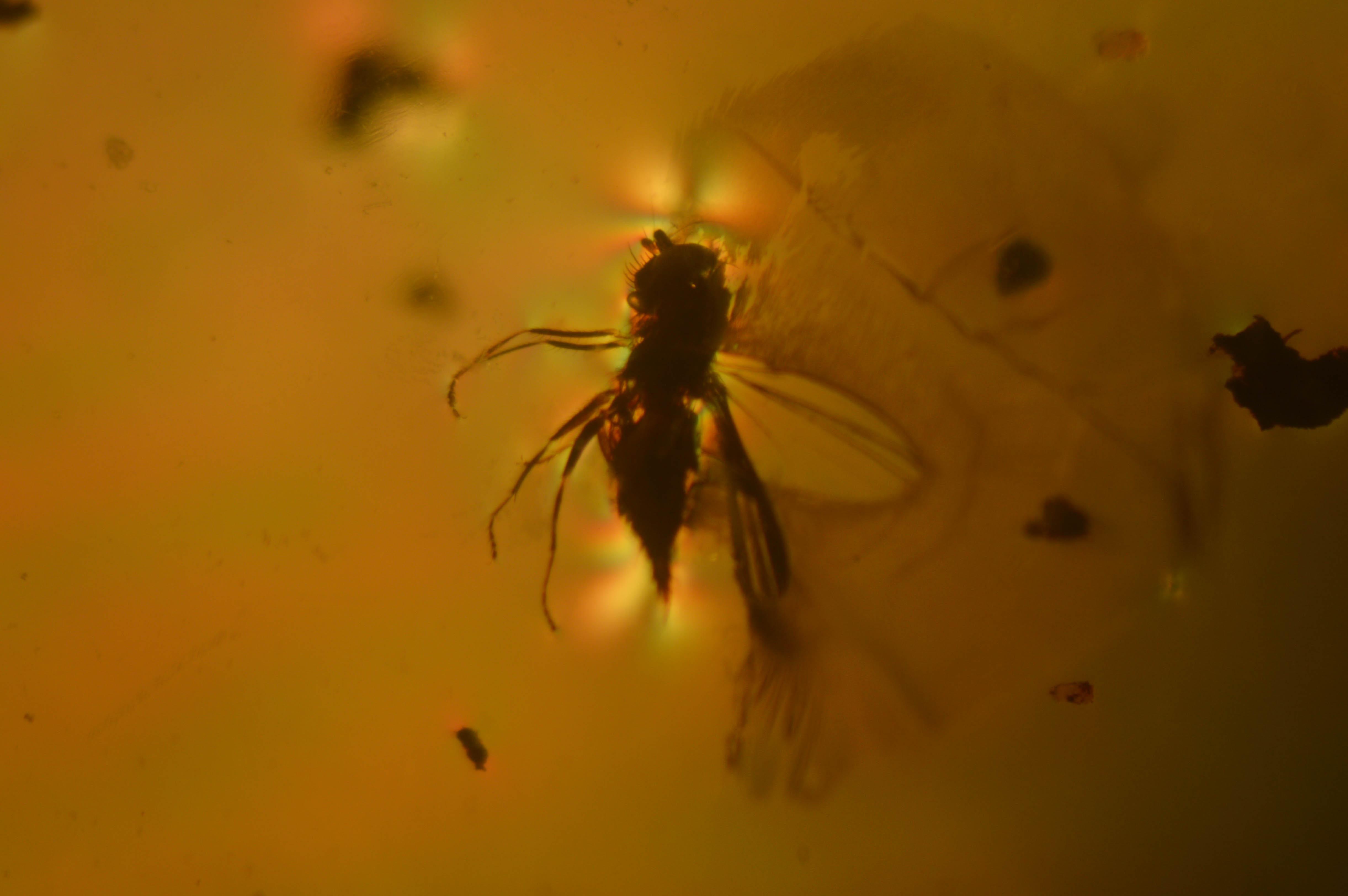

The most important plant inclusions were represented by a petal and a leaflet of the genus Hymenaea, more precisely the species Hymenaea mexicana, which is now extinct. Animal inclusions were more common. They consisted of arthropods such as winged termites and a planthopper. Isolated termite wings were detected as well.

The presence of isolated termite wings is extremely rare and the planthopper species, Nogodina chiapaneca, has only been found in amber samples from Chiapas. It is an extinct species dated to the Middle Miocene, and it lived in a tropical or subtropical climate. The presence of an arthropod of the genus Ochlerotatus (female mosquito) also indicates an aquatic environment.

Figure 2: (TOP) A flower petal inclusion of the species Hymenaea mexicana (Fabaceae family, Late Oligocene–Early Miocene; Poinar and Brown, 2002 and Calvillo-Canadell et al., 2010) is seen in this Mexican amber sample. The petal measures 1.1 cm long and 0.7 cm wide, and shows a narrow midrib base and basal laminar lobes with a central vein and branches of secondary veins. It appears completely glabrous (smooth). (MAIN ARTICLE IMAGE) The H. mexicana leaflet in this Mexican amber measures 3.3 cm long and 1.1 cm wide. The surface is glabrous and its veins are not visible in this view. Photomicrographs by V. L. Villani.

Figure 3: A planthopper of the species Nogodina chiapaneca (order: Hemiptera, family: Nogodinidae; Solórzano Kraemer and Petrulevicius, 2007) is shown at the bottom of this sample. It measures 11 mm long, and displays a rounded head and a clearly visible thorax with one foreleg. The wings have several veins, but the scales are not preserved. This species is known only from Chiapas amber. Photomicrograph by V. L. Villani.

Figure 4: These winged termites and isolated wings (rare in Mexican amber) of the order Isoptera (reclassified as part of Blattodea) were likely trapped at the beginning of the wet season, when termites start to swarm and then shed their wings. The length of the wings is ~1.1 cm. Photo by V. L. Villani.

What about X-ray powder diffraction?

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), is an instrumental technique that is used to identify minerals, as well as other crystalline materials.The method is based on the scattering of x-rays by the crystals. X-rays are diffracted by each mineral differently, depending on what atoms make up the crystal lattice and how these atoms are arranged. An X-ray scan provides a unique “fingerprint” of the mineral.

Natural resin/amber is amorphous, so XRD analysis does not yield information on the amber itself but can identify mineral inclusions. XRD identified very small amounts of refikite and hartite, as well as calcite. Calcite was identified by a diagnostic peak at 3.03 Å (or 29.8° 2θ) in the amber from Chiapas only. Refikite and hartite have a composition similar to that of resin, but possess a crystalline structure. They are probably associated with the polymerisation process of the resins.

What about amber classification?

Amber can be classified according to two criteria: their place of origin, and their chemical composition. When succinic acid is present the amber is classified as succinate, when succinic acid is lacking it is considered as a resinite.

Mass spectrometry was performed to determine the presence of free succinic acid in the amber samples. Confirmation of succinic acid is obtained from the m/z 117 ion (the negative ion mass peak) corresponding to (M-OH)– of succinic acid. The mass spectrum of the Mexican amber did not show the m/z 117 ion, so the level of succinic acid in this amber was lower than the limit of quantisation (1 ppm by weight), classifying it as a resinite.

The Dominican sample showed a spectrum very similar to that of the Mexican amber, indicating the absence of succinic acid, while the m/z 117 ion was clearly identifiable in the spectrum of the Baltic amber sample.

What about Infra-red spectroscopy and the “Baltic Shoulder” in Baltic amber?

Infra-red spectroscopy is the most effective scientific method for identifying fossil resins. With this technique, broad absorptions will be witnessed in Baltic amber in the 1260-1160 cm-1 range. Those are assigned to C-O stretching vibration. These features known as “Baltic Shoulder” are specific to Baltic amber and are related to the presence of succinic acid.

Three wavenumber ranges that are important for amber characterisation are 3700–2000 cm–1, 1820–1350 cm–1 and 1250–1045 cm–1; these regions are associated with hydroxyl and carbonyl groups and to C=C double bonds.

Figure 15: FTIR spectroscopy of a Mexican (Chiapas) amber shows typical peaks at: 3600–3100 cm–1 (broad absorption band due to the O-H stretching vibration); 2965 and 2860 cm–1 (C-H stretching); 1740 cm–1 (C=O stretching, esters and acid groups); 1450 and 1380 cm–1 (C-H aliphatic hydrocarbons); 1260–1030 cm-1 (C-O stretching aromatic esters and secondary alcohols); and 846 cm–1 (C-C stretching of unsaturated olefins).

Figure 15: FTIR spectroscopy of a Mexican (Chiapas) amber shows typical peaks at: 3600–3100 cm–1 (broad absorption band due to the O-H stretching vibration); 2965 and 2860 cm–1 (C-H stretching); 1740 cm–1 (C=O stretching, esters and acid groups); 1450 and 1380 cm–1 (C-H aliphatic hydrocarbons); 1260–1030 cm-1 (C-O stretching aromatic esters and secondary alcohols); and 846 cm–1 (C-C stretching of unsaturated olefins).

The fossil inclusions observed in Chiapas amber in this study are consistent with a sub-tropical forest and FTIR spectroscopy was confirmed as a useful technique to determine the provenance of the amber samples.

This is a summary of an article that originally appeared in The Journal of Gemmology entitled ‘Characterization of Mexican Amber from the Yi Kwan Tsang Collection‘ by Vittoria L. Villani, Franca Caucia, Luigi Marinoni, Alberto Leone, Maura Brusoni, Riccardo Groppali, Federica Corana, Elena Ferrari and Cinzia Galli 2017/Volume 35/ No. 8 pp. 752-765

Interested in finding out more about gemmology? Sign-up to one of Gem-A’s courses or workshops.

If you would like to subscribe to Gems&Jewellery and The Journal of Gemmology please visit Membership.

{module Blog Articles Widget}