Dyeing is probably the most common and cheapest way to treat gem materials, to make inferior stones seem to be of good quality or to substitute inexpensive materials for costly natural stones. Here, Gem-A Gemmology Tutor Pat Daly takes a closer look at dyed material and explains how experienced gemmologists can identify evidence of such treatments.

Gemstone dyeing is the introduction of coloured substances into permeable pale-coloured stones. Most such stones are translucent to opaque because they contain pore spaces that can accommodate the dye, but some are transparent stones that are heavily fractured when they are mined or are deliberately fractured so that dye can soak into them.

How Are Gemstones Dyed?

Stones are immersed in chemicals or pigments in solution after prior heating or chemical treatment to expand fractures and pore spaces. Colour is fixed by chemical reaction, heat, or by using wax or resin to close the pores.

Quarts dyed, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Pigments may be transported by water or some other fluid so that they remain inside the stone after the liquid has dried. This is a cheap method which may be satisfactory, but it uses dyes that might fade on exposure to light or wash out of a stone when it becomes wet.

Permanent Gemstone Dyes

Other dyes are permanent. Inorganic chemical treatment in Idar Oberstein, Germany, has produced agates in almost every colour, and these are widely used in the jewellery trade.

Sugar treatment is an example of a chemical treatment in which stones are dyed black with carbon. No generally useful fluid dissolves carbon, but sugar contains it, together with oxygen and hydrogen. Porous opal and agates may be soaked in a hot sugar solution and then in hot sulphuric acid, which absorbs these two elements. Carbon is left behind in pore spaces, giving a dark appearance to an opal, against which its play of colour is displayed to better effect, or an even black colour to agate, an appearance which is rare in nature.

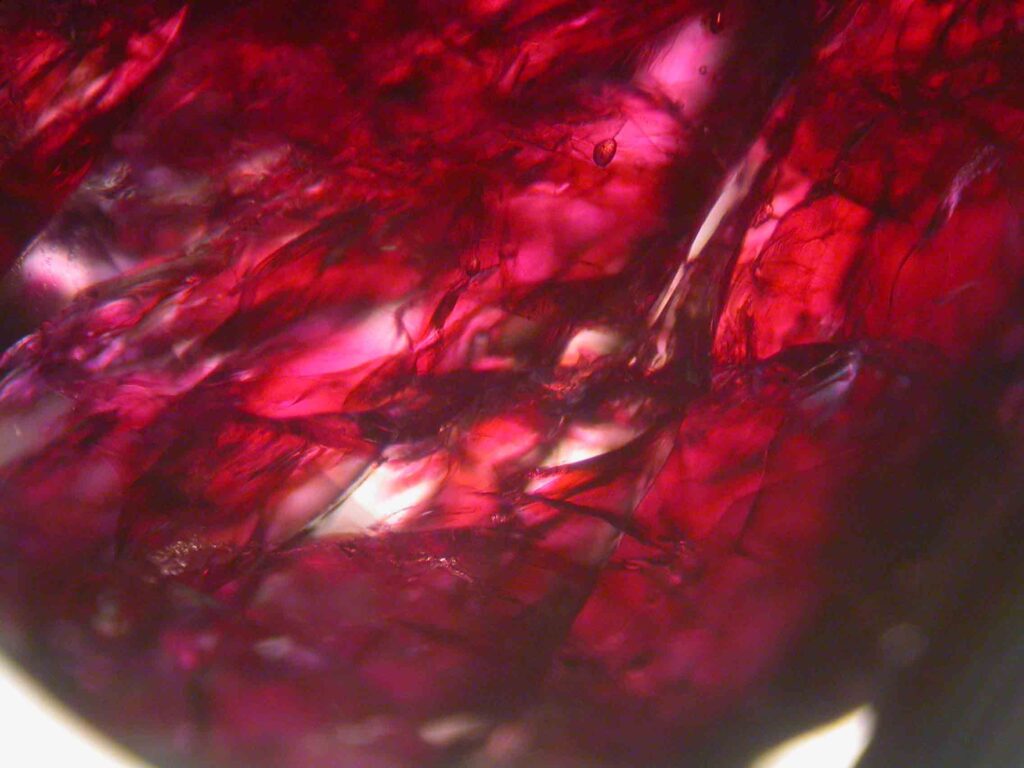

Concentrations of colour in a dyed ruby, photographed by Pat Daly.

Dying to Enhance Gemstones

In the past, it was common practice to dye marble statuary for decorative reasons, and this tradition is still observed in some cultures, but gemmologists are concerned with the imitative enhancement of gemstones. Dyeing can enhance any sub-transparent and some near-transparent stones. Common examples of the former include jadeite, opal, lapis lazuli and pearls. Materials that can be dyed to look like gemstones include quartzite, magnesite, and marble. Near-transparent stones include corundum, usually coloured red or blue, and quartz, which may be dyed to any colour.

Dyed magnesite, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Dyed magnesite, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Dyed stones, whether they are simulants or poor-quality stones, the colour of which has been improved, have much lower values than the materials which they resemble, so it is important for gemmologists to recognise the substitution. Some features are common to most dyed stones, others may be useful in particular cases, and these must be learned.

Common Visual Features of Dyed Stones

Dye concentrates in pore spaces and fractures in stones. It is usually possible to see this kind of colour distribution when inspecting a stone carefully with a loupe or microscope, and, in most cases, it confirms dyeing. Yellowish brown to reddish brown colour in fractures may be caused by iron compounds in stones which have been weathered at Earth’s surface, so care needs to be taken when interpreting these features.

Dyed freshwater pearls, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Dyed freshwater pearls, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Dyes may be soluble in acetone or its substitutes. A small swab dipped in one of these liquids may be stained with the colour of the dye when it is rubbed against a stone. This test is not infallible; some dyes are insoluble, and others may be protected by resin or wax.

Absorption Spectra in Dyed Gemstones

Absorption spectra may be absent or may differ from those of naturally coloured stones. For example, a pale corundum dyed red to simulate a ruby would not show a ruby spectrum, or if it did, it would be too weak to account for the colour of the stone.

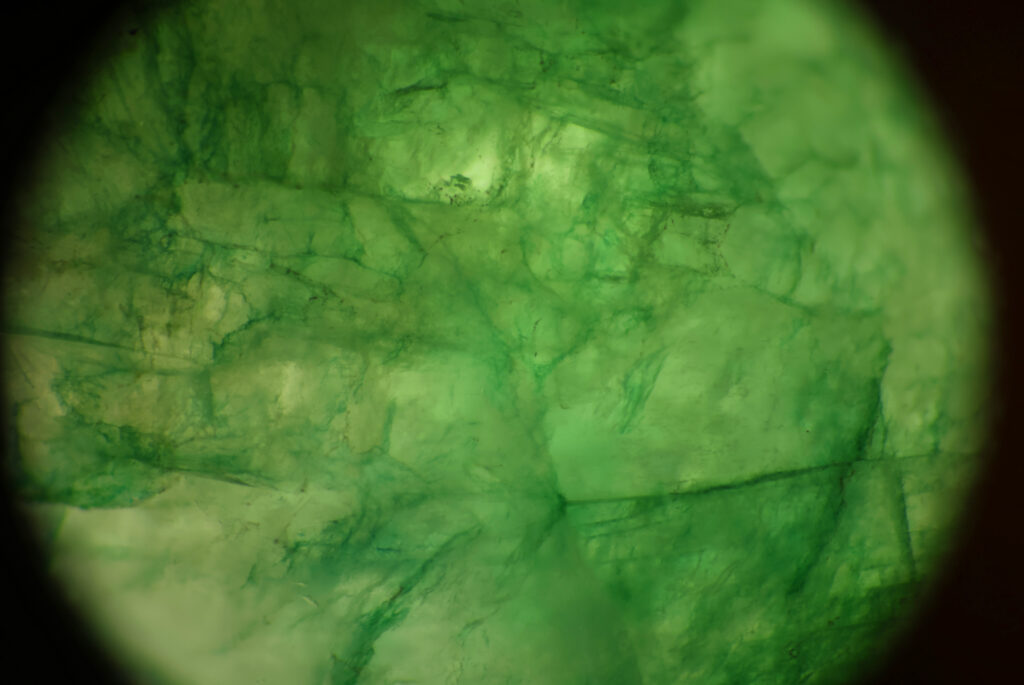

Most green jadeite has a chrome spectrum, of which it is usually possible to see fine lines in the red. Dyed green jadeite may have a broad band in the red or three broad bands in the red to orange, but it does not have fine lines in the red.

Dyed jadeite jade bangle with concentrations of colour, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Dyed jadeite jade bangle with concentrations of colour, photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

The colour through the Chelsea Colour Filter may be different for dyed and undyed stones. Chrysoprase, one of the most valuable varieties of chalcedony, looks green, whereas most dyed green agate looks greyish to pinkish.

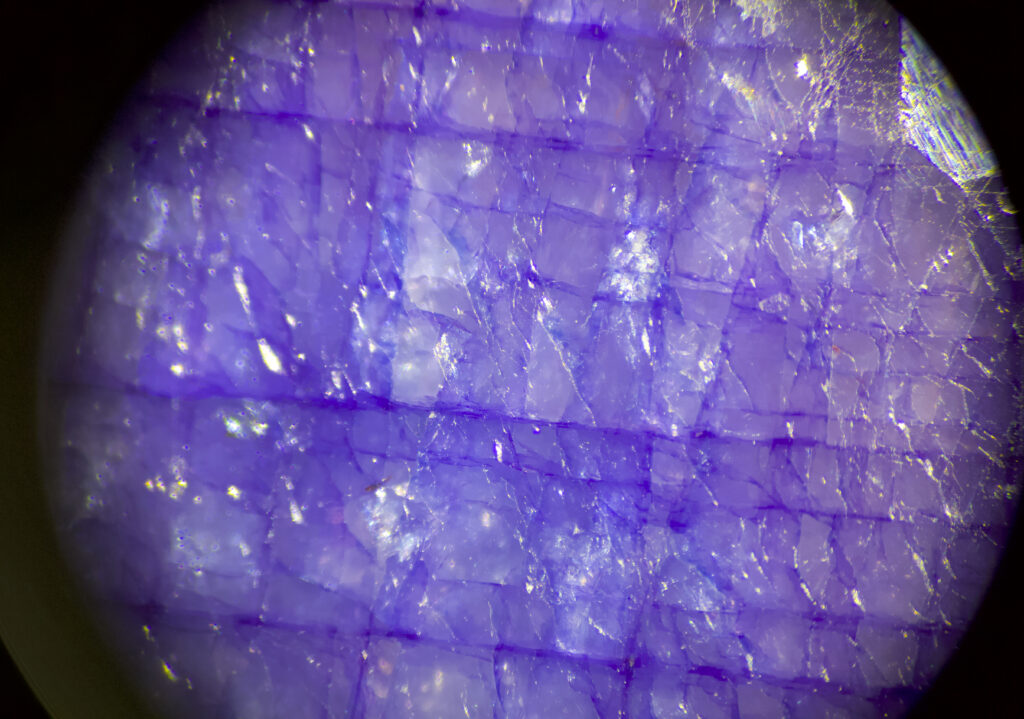

Luminescence may also differ. For example, some dyed lavender jadeite glows orange in long-wave ultraviolet, while undyed lavender jade (and some dyed stones) does not.

Dyed lavender jadeite (left) and dyed lavender glowing orange under LWUV, both photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Dyed lavender jadeite (left) and dyed lavender glowing orange under LWUV, both photographed by Gabriel Kleinberg.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Dyed Gems

Dyeing has several advantages for the jeweller and consumer. The range and quantity of pretty gemstones are increased, which means that lower-quality materials can substitute for expensive gem varieties. Attractive, colourful pieces may be made more cheaply and more adventurous designs may be tried by jewellers.

There are, of course, possible disadvantages. It may be hard to recognise that a stone has been dyed, and this makes it possible for mistakes to be made or for fraud. Gemmologists are responsible for preventing either from taking place, and it is our responsibility to be aware of the effects of dyeing and other treatments on gemstones, to be able to identify stones on which these have been carried out and to label or describe stones correctly so that those who handle them know what they are dealing with.

Main image: Dyed sapphire beads by Gabriel Kleinberg.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

If you would like to learn more about Gemmology, you can sign up for our mini online course GemIntro or explore our accredited programmes